This deep dive focuses on the Affordable Care Act, its impact on healthcare, and what's next. It can be used along with our Healthcare Reform Brief or as stand-alone reading material.

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

“The ‘Affordable Care Act‘ is the name for the comprehensive health care reform law and its amendments. The law addresses health insurance coverage, health care costs, and preventive care. The law was enacted in two parts: The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was signed into law on March 23, 2010 and was amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act on March 30, 2010.”

As The Policy Circle Healthcare brief outlines, before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (also known as “Obamacare” or the ACA) was signed into law on March 23, 2010, a bipartisan consensus agreed that clear and pressing problems existed with the status quo of healthcare in the United States, including the following:

- Those who suffered from serious and costly pre-existing health conditions were effectively “uninsurable” on the individual market due to the enormous cost of insuring them.

- Employers heavily subsidized health insurance, but Increasing healthcare costs still kept workers’ wages flat.

- The insurance market was skewed toward large employers; with smaller risk pools and less buying power, many medium and small-sized companies found it difficult to provide comparable insurance benefits.

- Individuals who wished to buy health insurance for themselves and their families were offered the least-attractive plans, with steep premiums and meager benefits.

- Many insurance plans did not include coverage for things that were likely to happen, such as maternity care or mental health and substance abuse counseling.

To address many of these pressing problems, the Democratic-controlled Congress supported the passage of the ACA. The major components, which were not without controversy, included:

- An individual mandate requiring everyone to obtain insurance or pay a penalty (unless they qualified for certain exemptions, such as those based on income. This penalty has since been eliminated).

- Subsidized and regulated insurance through new government exchanges, or coverage through Medicaid for millions of people who were unable to get health insurance (or good health insurance) through employers.

- A mandate that insurance companies offer health insurance to people with pre-existing conditions on the same terms as others.

- A requirement that health insurance plans include a minimum package of benefits to constitute adequate health insurance, including the “10 Essential Health Benefits.”

- A new tax on expensive employer-provided policies and management of federal healthcare dollars by experts in Washington, D.C., which would control government spending.

How Did The Affordable Care Act Become Law?

It is important to understand both the circumstances before the ACA’s passing, as well as the context around how it became law. Radio host Brian Sussman provides a quick rundown on what happened.

In September 2009, then President Obama held a joint session of Congress to outline his healthcare reform measures. By November, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives passed its healthcare bill by a slim margin (220-215), along mostly partisan lines. The bill originally included a public option, where a government health insurance program like Medicare would compete against private health insurance, and Americans could choose from either the public option or a variety of public plans. The Senate, also with a Democratic majority, then began its debate, but it was clear the public healthcare option in the House bill would not pass the Senate. This made the fate of the legislation uncertain, because all revenue-raising bills must originate in the House.

To work around this requirement, the Senate took H.R. 3590, which originated in the House as a military housing bill, and completely rewrote it to become the ACA. It passed 60-39 on December 24, 2009. The Senate sent the bill back to the House, but if the House made any further changes, it would need to pass the Senate again. This presented a potential problem, as the Senate seat that had been occupied temporarily by Democrat Paul Kirk after the death of Senator Ted Kennedy had since been filled by Republican Scott Brown. The election of Brown reduced the Senate Democrats’ seats to 59, one short of the 60 votes needed to approve further changes in the House version.

In March 2010, the House agreed to pass the Senate version “as-is” to avoid sending the bill back for Senate approval. It passed without one Republican vote. The Senate used a “reconciliation procedure,” a measure not designed for major policy bills that only requires 51 votes to pass. The House then immediately passed an amendment that made changes to the Senate version, called the Reconciliation Act of 2010, which passed the Senate immediately after. President Obama signed the Act on March 23, and the amendment on March 30 (Britannica).

Who is Impacted by the ACA?

Insurers

The ACA established new rules in the insurance marketplace that directly impacted insurers, mainly along the lines of cost. For example, insurers were no longer allowed to look at subscribers’ pre-existing conditions when offering and pricing health insurance plans, and the ACA also placed a limit on the amount from premiums insurers could devote to profit. Based on these changes, insurers had to choose whether or not they would participate in the ACA marketplace. These strict regulations limited insurance companies’ profits and freedom of action in ACA marketplaces, but a growing number of insurers have decided to join state exchanges in the decade since the ACA was passed.

Drug Companies

One ACA provision imposed a tax on pharmaceutical companies based on sales revenue from brand-name drugs. Pharmaceutical companies passed these tax costs on to their customers in the form of higher drug prices. Another major component of the ACA was the option for the states to expand their Medicaid programs. Due to laws that require drug manufacturers to provide a fixed rebate or “best price” available, “drug manufacturers became obligated to provide their drugs for roughly three-quarters of the price to nearly a quarter of the U.S. population” (AAF).

Employers and Employees

The ACA does not require all employers to provide health benefits, but larger ones (with at least 50 full-time employees) can be penalized for not offering coverage or affordable coverage to workers. More offerings, however, do not mean lower healthcare costs for either employers or employees, as the chart shows. About 10% of adults with insurance still have trouble paying medical bills, and almost half of adults say it is difficult to pay for out of pocket medical costs.

The ACA does not require all employers to provide health benefits, but larger ones (with at least 50 full-time employees) can be penalized for not offering coverage or affordable coverage to workers. More offerings, however, do not mean lower healthcare costs for either employers or employees, as the chart shows. About 10% of adults with insurance still have trouble paying medical bills, and almost half of adults say it is difficult to pay for out of pocket medical costs.

Unemployed Americans

Unemployed Americans are able to find individual or family health insurance plans on the ACA Marketplace, since household size and income are the determining factors. Americans who have left their job for whatever reason and lost employer coverage qualify for a “Special Enrollment Period” in which they can enroll in an insurance plan any time of the year within 60 days of losing prior insurance, instead of waiting for the Marketplace enrollment period.

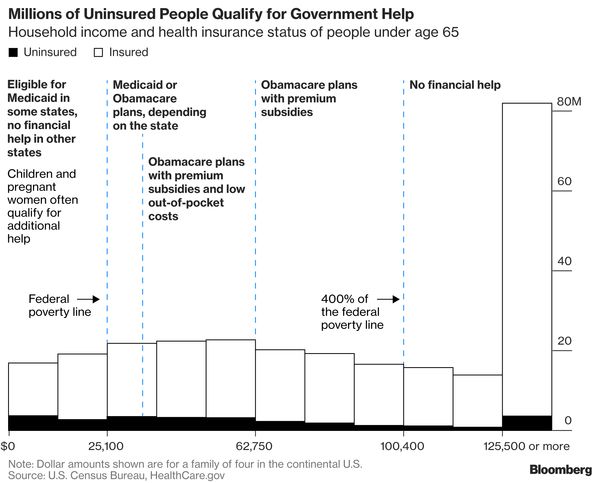

Access to health insurance was a major challenge for Americans who lost their jobs in 2020. In response to this, the 2021 American Rescue Plan provided health insurance subsidies for anyone receiving unemployment assistance in 2021, and expanded the subsidies already available to many Americans.

Healthcare Providers

Uncertainty regarding the ACA cast it in an unfavorable light among doctors and healthcare practitioners. In 2016, 51% of doctors in a CompHealth poll held an unfavorable view of the ACA (particularly private practice physicians, as opposed to hospital-based physicians), and only 30% viewed it positively. Over 40% of healthcare providers claimed the ACA negatively impacted the costs of healthcare, doctors’ salaries, and doctors’ abilities to meet patient demands. Sally Pipes of the Pacific Research Center adds that Medicaid pays healthcare providers less than private insurance pays, so many doctors refuse Medicaid patients, which leads to an increased use of emergency rooms.

What's the Current Status of the ACA?

The Affordable Care Act got off to a rocky start that included constant website crashes as people were trying to enroll and debacles surrounding canceled insurance plans Americans were told they could keep. Additionally, as the ACA did not pass Congress on a bipartisan basis, it has faced a series of challenges put forth by Congress, states, and attorneys general.

The Individual Mandate

The individual mandate was one of the least popular provisions of the ACA. Its goal was “to encourage healthy individuals to participate in the insurance market and not wait until they get sick to buy coverage,” as well as spread out the cost of sicker people who would enroll and use more services (CRS). In 2012, the National Federation of Independent Businesses challenged the constitutionality of the individual mandate in NFIB v. Sebelius, and in 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it was constitutional. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed in December 2017, repealed the ACA’s individual mandate penalties, effective January 1, 2019. The repeal did not actually remove the mandate from the law, but rather rendered the mandate null by reducing the penalty to $0.

Medicaid

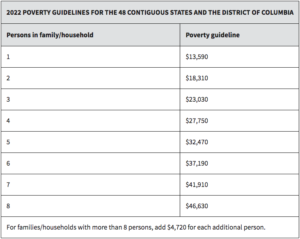

The ACA expanded Medicaid, which was previously only for specific populations including low-income children, seniors, or disabled persons. The expansion allowed any individual (notably childless adults) with low income (up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level) to be eligible for Medicaid. In June 2012, the Supreme Court ruling in NFIB v Sebelius found the Medicaid expansion “to be unconstitutionally coercive,” and prohibited the federal government from making the expansion mandatory for states (CRS). As of mid-2022, 38 states and Washington, D.C. have accepted federal funding to expand Medicaid (see which ones here).

The ACA expanded Medicaid, which was previously only for specific populations including low-income children, seniors, or disabled persons. The expansion allowed any individual (notably childless adults) with low income (up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level) to be eligible for Medicaid. In June 2012, the Supreme Court ruling in NFIB v Sebelius found the Medicaid expansion “to be unconstitutionally coercive,” and prohibited the federal government from making the expansion mandatory for states (CRS). As of mid-2022, 38 states and Washington, D.C. have accepted federal funding to expand Medicaid (see which ones here).

What does expanded Medicaid look like? Both enrollment and total costs have been higher than anticipated, mostly due to the federal match to state spending. According to the most recent CMS report (from 2018), Medicaid provided health care to 73.4 million enrollees in 2017, 12.2 million of which were expansion adults. Spending for expansion adults is projected to grow by about 6% annually, from $74.2 billion in 2018 to $124.3 billion in 2027. Most of this spending (approximately 90%) will be financed by the federal government.

A 2017 Health Affairs study found expansion led to an 11.7% increase in overall Medicaid spending, and while the federal matching rate may help states save money, it does not provide states an incentive to be efficient and vastly increases federal spending. Between 2013 and 2014, federal Medicaid expenditures increased by 13.6% due to large increases in Medicaid enrollment. The CBO predicts federal Medicaid spending will grow by 6% per year until 2029.

What Are the Results of the ACA?

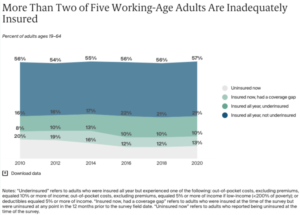

As illustrated above, healthcare policy is not easy. Despite being called the Affordable Care Act, the ACA did not excel in making healthcare affordable, although it did expand coverage to millions of Americans. In the U.S. today more people can say they have healthcare coverage since its implementation. Unfortunately, having health insurance doesn’t mean you won’t have a bill due after you have gone to a healthcare provider. Even with health insurance, some people still avoid doctors offices because they can’t afford to pay for care: more than 2 of every 5 working adults are inadequately insured, meaning out of pocket costs like were 10% or more of income.

Some say it’s a true, clean-functioning market mechanism that will improve care and decrease costs. The ACA went in the opposite direction by inserting a larger government role in healthcare, which can lead to an increase in unintended consequences in the healthcare market.

Coverage

Before the ACA, individual market insurers could charge higher premiums or deny coverage to applicants with pre-existing conditions because they were considered risks. CMS estimates between 50 and 129 million non-elderly Americans, including 4 to 17 million children under age 18, have at least one pre-existing condition that could threaten their health insurance without ACA protections. Pre-existing conditions also affect older Americans, who are more likely to have or to have had a health condition: based on conditions insurers generally look for in a patient’s medical history, 86% of people ages 55 to 64 could be denied coverage without added protections. Examples of pre-existing conditions include cancer, diabetes, and sleep apnea.

Under the ACA, insurers were no longer allowed to deny these populations coverage or charge them at higher rates. This stipulation along with federal subsidies helped many people without employer-provided health benefits attain insurance. Unfortunately, opening a government-funded market to more sick people who have not maintained health coverage (and likely have not maintained their health check ups) is going to increase costs of care for everyone in the system.

The ACA expanded coverage to almost 20 million people, meaning more Americans have access to health insurance. Before the ACA expansions in 2012, 72% of uninsured adults had been without coverage for over 2 years; in 2018, this number had decreased to 54%. Additionally, coverage gaps have become shorter. In 2012, only 35% of people experiencing gaps in coverage were able to find and enroll in a new plan in fewer than 6 months. Since the 2012 expansions, this has increased to over 60%.

Although uninsured rates are still at all-time lows, the number of uninsured Americans rose for the first time in a decade between 2017 and 2018. This appears to be mostly due to a positive change: declines were primarily in Medicaid coverage because rising wages have left fewer people in need of Medicaid. The uninsured rate among Americans has stayed fairly stable since 2018; based on data from the Commonwealth Fund, the rate is between about 11-14%, and there were no significant changes in coverage over the course of 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, many insurers have left the marketplace. This has required those who lost coverage due to a failed insurer to start from scratch to meet deductibles and other out-of-pocket expenses with a new provider. As a result, many individuals have opted out of insurance altogether, especially since the individual mandate was rendered null.

Insurers

According to the Wall Street Journal, UnitedHealth Group’s insurance exchange unit lost $425 million in 2015, and in 2016 estimates rose from $525 million in losses to $650 million. CEO Stephen Hemsley said UnitedHealth would withdraw to “only a handful of states” in 2017. In 2018, Aetna withdrew from 223 counties across 4 states, Blue Cross Blue Shield withdrew from 105 counties across 3 states, and Humana from 155 counties across 11 states. For 2020, Aetna and Humana did not offer ACA plans.

Lack of overall growth in the ACA market made insurers that pulled out, like Aetna and Humana, stay away. This caused the Marketplace to contract, and those insurers that remained sharply increased their rates to offset their predicted costs of remaining in the Marketplace. In 2017 and 2018, these companies began to generate profits. Financial performance data from 2020 suggests insurers were profitable throughout the pandemic, indicating stability of the market. Only a limited few insurers decreased premiums for 2020, but premiums appeared to fall 1-4% for 2021.

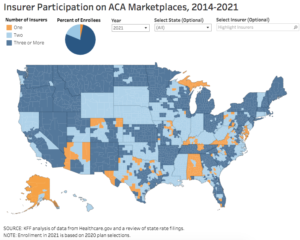

Some insurers, including Cigna and Centene, announced further expansion of their offerings, and others re-entered the market. After dropping to 3.5 insurers per state in 2018, marketplace insurer participation grew to 5 per state in 2021. Almost 80% of enrollees have at least three insurers to choose from, up from 60% in 2019.

Not all companies participate statewide. More than 200 counties have at least five insurers participating in 2021, and only 10% of counties have only one insurer offering (down from 52% of counties in 2018). Rural areas most often have the fewest insurance options. For 2021, metro-area counties had an average of 3.1 insurers and non-metro areas had an average of 2.5 insurers.

Insurer Costs

Medical Loss Ratio (MLR)

The ACA Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) was a controversial rule. It was meant to provide consumer protections against overpriced health plans but at the same time involved the federal government dictating how businesses should handle their finances. MLRs require health insurers to spend at least 80% of premium revenue on claims or quality improvement expenses, rather than on administrative costs. If profits from premiums exceed 20%, insurers must rebate the excess to consumers (Commonwealth Foundation). Because profitability has been increasing since 2018, insurers continue to issue high amounts of rebates. In 2019, insurers issued $1.4 billion in rebates, the highest rebate amount of any year since the ACA was implemented in 2010. In 2021, rebates were 2.14 billion.

Even though insurers have been generating more profits, they are warning that losses from the past decade of the ACA are unsustainable. In the fall of 2019, the Supreme Court heard a $12 billion suit from insurers against the federal government regarding the so-called “risk corridor” program. The program was established to “help insurance companies cope with the risks they took on when they decided to participate in the marketplaces.” Under the program, insurers were entitled to government compensation if they paid out more on policy claims than they took in from premiums.

For fiscal years 2015, 2016, and 2017, Congress passed appropriations bills with riders that barred the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) from making such compensation payments with general funds. This meant the government could only compensate insurers with money collected from insurers who paid less on claims than they took in from premiums. These funds have not been enough; HHS statistics indicated in 2017 the shortfall was $12 billion. In April 2020, the Supreme Court ruled the government was obligated to make full risk corridor payments.

Cost-Sharing Reduction Program

The Cost-Sharing Reduction (CSR) programs introduced in the ACA were meant to compensate insurers for the cost of healthcare for people who signed up for ACA plans. These programs help cover some of the expenses of deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance for people with incomes below 250% of the Federal Poverty Level. In 2014, the Republican-led House of Representatives sued HHS, arguing CSR payments to insurers were improper because HHS did not have congressional appropriation. A federal district judge agreed, finding in House v. Azar in May 2018 that HHS could not constitutionally reimburse insurers without explicit congressional appropriation. As of February 2019, there have been at least 12 separate lawsuits filed by insurers against HHS in the Court of Federal Claims for unpaid CSRs, including a class action lawsuit with 91 insurers. The majority of judges have found insurers entitled to unpaid CSRs, regardless of explicit congressional appropriation. This means the government owes more money to insurers, adding to the already ballooned fiscal burden of healthcare – just another illustration that nothing is easy in health care reform and much of government activity drives consequences no one was expecting. It is very difficult to lower the cost of healthcare for consumers without harming the financial interests of at least one set of stakeholders such as private insurance companies.

Subscriber Costs

The CBO estimated net federal subsidies for health insurance coverage would total $920 billion in 2021, and total $10.8 trillion cumulatively between 2021 and 2030. While about 5% of federal subsidies amount go directly towards providing people coverage under the ACA, another 45% goes to Medicaid payments to states and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which includes the Medicaid expansion plans enacted under the ACA.

In the U.S., healthcare costs continue to rise faster than Americans’ incomes: For individual Americans, “the cost…to buy a health plan – if they don’t get it from a job or the government – is higher than ever.” When insurance companies could no longer charge sick people more or refuse to cover them, costs for healthy people went up. The government doesn’t generate income except from what it collects from taxpayers, so it needs to find revenue sources to pay for its programs, such as the ACA. In this case, it forced insurers to foot the bill, and they charged healthy people more to pay for sick people. This is why premiums have risen so rapidly.

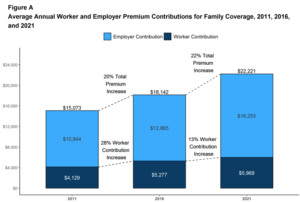

One 2019 analysis showed that as premiums increased, the proportion of consumers buying ACA health plans without federal subsidies declined as these out-of-pocket costs became too much for many households. The average family premium increased 22% between 2016 and 2021, and 47% between 2011 and 2021.

In the employer market, businesses have had workers take on increasing shares of health costs; the ACA employer mandate, another controversial component, imposed a minimum coverage requirement, but employees can still have a large bill as well as high deductibles and copayments. The average annual premium for employer-based family coverage rose 4% from 2020 to 2021, to $22,221. For single coverage, it rose 4% to $7,739. On average, covered workers contribute 17% of premium costs for single coverage ($1,299) and 28% of premium costs for family coverage ($5,969).

These annual increases have large, long term effects. Families like the Buchanans in North Carolina saw their 2018 insurance premium of $1691 per month (already triple their mortgage payment) increase to $1831 for 2019. On top of their $5000 per-person deductible, having and using their insurance could cost them over $30,000 annually. Like many other American families across the nation, they are reevaluating their budget and saying, “We’re not poor but we can’t afford health insurance.”

Underinsured Americans

Increases in costs have left more people than ever underinsured. Being underinsured means having health insurance coverage, but not being able to use it because of the compounding costs of actually receiving care. Due to high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles, an estimated 45 million people were underinsured in 2020, up from 29 million in 2010. Compared to insured adults with adequate coverage, underinsured adults are more than twice as likely to not fill a prescription, to skip a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up appointment, and to have medical debt.

Increases in costs have left more people than ever underinsured. Being underinsured means having health insurance coverage, but not being able to use it because of the compounding costs of actually receiving care. Due to high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles, an estimated 45 million people were underinsured in 2020, up from 29 million in 2010. Compared to insured adults with adequate coverage, underinsured adults are more than twice as likely to not fill a prescription, to skip a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up appointment, and to have medical debt.

Consumer Oriented and Operated Plans (CO-OPs)

CO-OPs were originally created by the Affordable Care Act to “create new, private non-profit health issuers set up through the Exchanges” and “to provide affordable health insurance to their members and increase competition and choice in the marketplace.” As of 2021, only three of the original 23 CO-OP plans are offering coverage in five states. The three CO-OPs selling plans “are showing signs of overall stability,” but two have successfully implemented rate decreases for 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Why did most of the CO-OPs fail? Like all plans, the co-ops underpriced the cost of covering people at the onset of the exchanges. Premiums were too low, benefits were too generous, and competition from bigger health insurers with larger reserves overwhelmed the CO-OPs. Unlike private insurers, the CO-OPs “did not have the savings on hand to make up for their losses in initial years.”

Rural Disparities

Healthcare CO-OP closures narrow consumers’ choices, and counties that are mostly rural are disproportionately affected. In almost two-thirds of rural counties, a CO-OP offered one of the two least expensive silver plans.

Rural hospitals also continue to face reimbursement cuts and regulations that many hospital administrators and board members say have caused more harm than good. Since the Affordable Care Act was passed, rural critical-access hospitals have closed at an increasing rate. According to The North Carolina Rural Health Research Program (NC RHRP) at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, there have been 181 rural hospital closures since 2005. More than half of all rural hospital closures since 2010 were in the South and few Southern states have expanded Medicaid under the ACA.

VICE takes a closer look at hospital closures and the state of healthcare in rural areas (7 min):

Short-Term Plans

Since 2014, an unintended impact of the ACA has been an increase in the use of short-term plans. These plans are traditionally sold to consumers trying to fill gaps in their coverage for a few months. For many Americans, short-term policies cost significantly less than conventional ACA-compliant plans. However, because short-term plans do not have to comply with ACA market reforms, short-term insurers can charge higher premiums, exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions, and require higher out-of-pocket costs. On average, short-term plans pay out 67% of their earnings on medical care, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. As noted earlier, ACA plans require insurers to spend at least 80% of premium revenue on medical claims. This means brokers and insurers of short-term plans generate more revenue than ACA plans (KHN).

By HIPAA definition, short-term plans last no longer than 12 months from the effective start date. In 2010, the Obama administration limited short-term plans to a maximum duration of three months based on concerns these plans were being sold as primary coverage. This trend is harmful to the goal of the ACA: short-term plans attract healthy people needed to help make the ACA finances work.

In October 2017, then-President Trump signed an executive order expanding the availability of short-term plans and expanding duration back to 12 months. A final rule went into effect in October 2018 with the goal of allowing short-term coverage to be sold alongside ACA coverage, and was upheld by a federal district judge in July 2019. The final rule also adopted a disclosure notice informing consumers that short-term plans may not cover services “such as hospitalizations, emergency services, maternity care, preventive care, prescription drugs, and mental health and substance use disorder services.” Administration officials estimated 600,000 people would enroll in short-term plans in 2019, with between 100,000 and 200,000 dropping ACA coverage to do so. Various states have taken their own actions to regulate short-term plans.

What's Next for the ACA?

Constitutionality

After the individual mandate tax penalty was reduced to $0, it opened the door for another challenge to the ACA. In Texas v. United States, Texas and 17 other states argue the Supreme Court upheld the individual mandate in NFIB v Sebelius as a tax only. Since the 2017 tax reform law eliminated the tax, “the ACA must be invalidated because the entire law depends on the mandate.”

A Texas federal judge agreed in December 2018 and declared the ACA invalid. California and 16 other states appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, arguing that the individual mandate can be separated from the rest of the ACA. Oral arguments took place in July 2019. The three-judge panel ruled the individual mandate was unconstitutional but sent the suit back to the Northern District of Texas to ask the judges “to consider how much of the ACA could remain with the individual mandate considered unconstitutional.”

California and the 16 other states then petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing the lower courts had created “uncertainty about the status of the entire Affordable Care Act.” The Supreme Court heard arguments in November 2020. In June 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in a 7-2 vote “that neither the states nor the individuals challenging the law have a legal right to sue, known as standing.” This means that the central issue of whether the ACA was rendered unconstitutional when the individual mandate was reduced to zero remains undetermined. WSJ legal affairs reporter Brent Kendall explains some background on the case in this podcast (4:45-9).

–

Congress failed to repeal and replace the ACA after several attempts in 2017, so it’s unclear what is on the horizon. Some lawmakers have suggested attempting bipartisan fixes, but it remains to be seen exactly what that may look like as no consensus on a replacement plan has been reached. However, several policy prescriptions have attracted widespread support:

- The ability to buy insurance across state lines to create more choice and competition;

- Cost transparency so people can know the price of their insurance and medical services.

Technological innovation and digitization to help providers adopt cost-saving measures and empower patients to be more in control of their treatment options.

Economic Incentives

Healthcare reform means trying to change a complicated set of rules and incentives for a variety of stakeholders, from individuals and families to private insurance companies and medical providers.

Health insurance companies can only make a profit if they have a large pool of healthy customers who pay more in premiums than they require in the form of claims for medical treatment. A small but significant pool of older customers with chronic and pre-existing conditions require far more in medical costs than they can afford to pay. Because it is not profitable for private insurance companies to take on these customers, these individuals would either be uninsured or underinsured with exorbitant health insurance costs.

The premise of the ACA was to ensure these individuals had insurance, through the individual mandate and requirements to cover pre-existing conditions. However, when insurance companies raised premiums across the board to cover costs because they could no longer charge a smaller group of customers much higher rates, healthier people who did not need as much medical care had a financial incentive to simply forgo health insurance.

Conclusion

We are a large, diverse nation that develops leading-edge, life-saving innovation for the entire world. Our efforts to perfect our hybrid government-private sector system to guarantee every single person in our nation access to quality and affordable healthcare is no small task. Healthcare reforms are constantly analyzed and new proposals are always under debate, and what the government-run ACA will ultimately look like is anyone’s guess. From calls to repeal and replace the ACA and lawsuits debating its constitutionality, to proposals to build on the ACA or even go beyond with other public options like Medicare-for-All, one thing is clear: the U.S. healthcare system is a complex beast that will continue to be reformed and improved upon.