We are known and remembered for how we give our time, talent, and treasures. This brief allows you to reflect on how you give, better define your values and goals, and boost your understanding of the opportunities and challenges in philanthropy. The brief highlights the role strategic giving plays in civic engagement and rejuvenating civic life in America.

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Whether at the grocery store checkout, a friend’s social media posts, or through our inbox or mailbox, we are asked to give back every day. Giving and service to others is part of America’s DNA. Upon coming to America, hopeful citizens started from scratch and built their communities with what they had. When French sociologist and political theorist Alexis de Tocqueville traveled to the United States in the 1830s, he was struck by American civil society, the extent of Americans’ civic engagement, and how people came together to champion causes that benefited the community.

To this day, his observation that a healthy democracy requires civil associations remains true. Harvard’s Robert Putnam echoes this sentiment: “Certain communities do not enjoy a more vital civic life because they are prosperous. They are prosperous because they have a vital civic life.”

Why it Matters

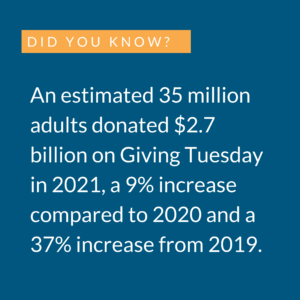

From the coronavirus pandemic and nationwide unrest to supply chain shortages and rising prices, America faced multiple crises since the beginning of 2020. A more encouraging note is the record amounts of giving that occurred in 2021. According to Giving USA, Americans donated a record $484.85 billion to charitable causes, demonstrating optimism and a desire for a better future.

Strategic philanthropy provides a unique opportunity to invest in real issues and move the needle on what matters most to you – from education to religion to social issues – and helps shape the civic landscape of your community.

While federal, state, and local governments are equipped to respond to and handle challenging issues, philanthropic freedom enables nonprofit organizations to fill government gaps and quickly react to society’s challenges with innovative and flexible solutions. And yet, policy debates about the nature of philanthropy and philanthropic freedom that enables charitable causes to do what they do best remain. When policies affect philanthropy, they directly impact active and constructive civic participation.

Putting it in Context

Definitions

Philanthropy, charity, and volunteerism are voluntary contributions of money, talent, and time to help develop communities or improve the lives of others. These means are “key factors in the development of communities and improvement of the lives of people in a donor’s home town or city, state, country, or even around the world.”

Charity and philanthropy “involve giving money directly to people or to causes or nonprofit organizations that help people,” but there are some subtle differences between the two. Charity is usually “an immediate response to a short-term need, such as sending a donation to the Red Cross after a natural disaster or giving a one-time gift to a nonprofit organization. Philanthropy is more strategic and focused on supporting individuals to solve problems over the long term. Author Matthew Smith describes the difference this way: “Delivering bottled water to a drought-stricken village in East Africa is charity, but philanthropy is building a well.”

Volunteerism is when individuals donate their time and skills, with no financial compensation, to an organization that serves other people.

By the Numbers

Historically, the U.S. has an international reputation for being one of the most giving countries in the world. Americans dedicate 2% of total U.S. GDP to charity, more than twice the average in the EU.

Volunteers make an enormous contribution to their local communities. According to Independent Sector, a national organization for nonprofits, foundations, and corporations, the value of an hour of a volunteer’s time in the U.S. in 2022 estimates at $29.95. Roughly 77 million Americans volunteered about 7 billion hours in 2020, valued at approximately $167 billion.

Charitable giving rose from $450 billion in 2019 to $484.85 billion in 2021. However, the number of households donating to charitable organizations has decreased recently. This means the vast majority of donations come from a smaller pool of people.

A July 2021 article by CBSNews.com explains one primary reason is that people simply can not afford to give because of “economic turbulence of the Great Recession.” US News reported on a study by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, which indicated that 88% of affluent households gave to charity in 2020, and charitable giving continued throughout the difficulty of the pandemic.

One shift in philanthropy is the shift towards social and racial causes. In 2020, 9% of wealthy households said they thought social and racial justice was important, up from 5.8% in 2017; and 25% of affluent households reported giving to social and racial causes in 2020. The reason? Quite simply, wealthy donors said they became more knowledgeable about these organizations and wanted to be purposeful in their giving to solve inequality-related problems further.

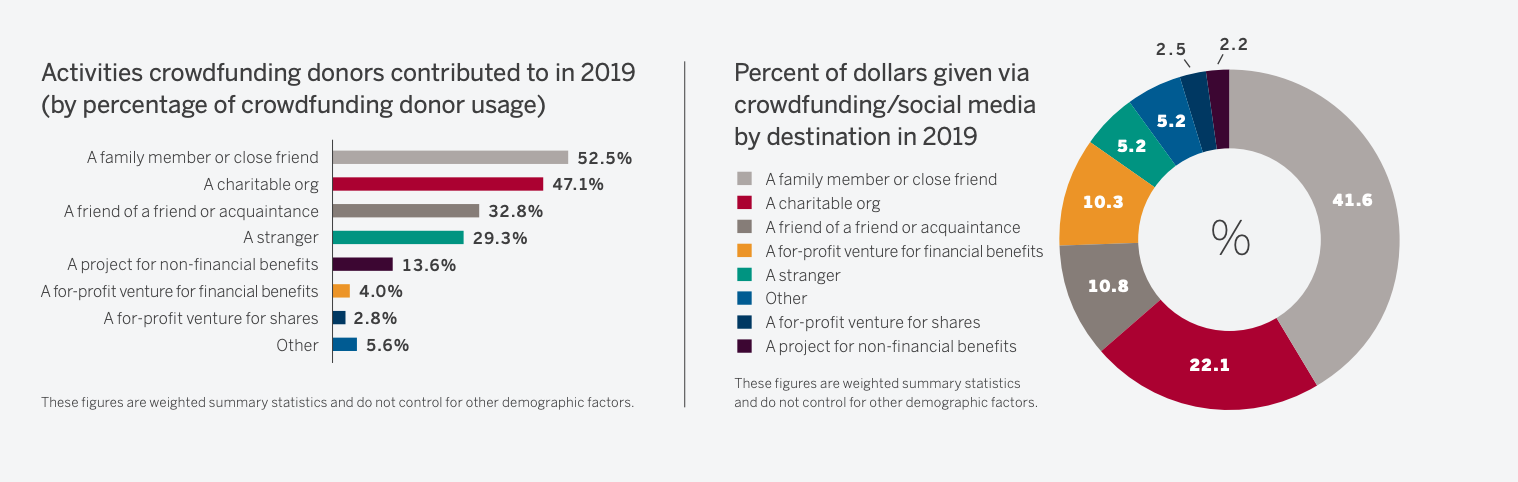

Younger Americans are less likely to affiliate with a religious group and are more likely to participate in crowdfunding campaigns for a cause due, in part, to the decline of trust in institutions.

Charitable donations vary greatly based on age, income, and education levels. For an in-depth look at charitable giving characteristics and demographics, take a look at Nonprofits Source.

Areas of Focus

According to Giving USA’s 2021 report, most nonprofit categories saw a boost in contributions, particularly among public-society groups such as civil rights organizations and charities like the United Way. However, arts and culture organizations, nonprofit hospitals, and disease-specific health organizations saw declines in giving.

Una Osili, Associate Dean for Research and International Programs at the Indiana University Lilly School of Philanthropy says some decline in health organization donations is explained by pandemic-related contributions, which had a 9% increase from 2019.

In 2020, the majority of U.S. charitable donations went to religion (28%), education (15%), human services (14%), and public-society benefit (10%). The top four types of organizations that received the most support through volunteering in 2020 were religious (32%); sport, hobby, cultural, and art organizations (25.7%); education or youth service organizations (19.2%); and civic, political, professional, or international organizations (6.2%).

In 2020, the majority of U.S. charitable donations went to religion (28%), education (15%), human services (14%), and public-society benefit (10%). The top four types of organizations that received the most support through volunteering in 2020 were religious (32%); sport, hobby, cultural, and art organizations (25.7%); education or youth service organizations (19.2%); and civic, political, professional, or international organizations (6.2%).

The Nonprofit Landscape

The Urban Institute’s Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy estimates there are 1.8 million registered nonprofit organizations in the U.S. The nonprofit sector includes organizations from endowed private philanthropic foundations to local associations. This Washington Examiner states, “An estimated 87,000 grant-making private foundations control more than $1 trillion in wealth and direct it independent of government.”

Most of these fall under an Internal Revenue Services 501(c) designation, classifying them as tax-exempt organizations. Tax-exempt charitable organizations include those “organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, education, or other specified purposes.”

501(c)(3)

Organizations that only operate charitable activities are classified by the Internal Revenue Code under Section 501(c)(3). These organizations are generally tax deductible and must use grants, donations, and other payments only for specified purposes. 501(c)(3)s are prohibited from engaging in political campaign activity and influencing legislation, but they are allowed to engage in limited lobbying through issue advocacy, discussed more below. The IRS classifies all 501(c)(3) organizations as either private foundations or public charities. The Policy Circle is a 501(c)(3).

Under the Internal Revenue Code, a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization is presumed to be a private foundation until it can prove it is a public charity. Public charities “are required to have a broad base of public support,” which the IRS measures by requiring at least one-third of donations to come from donors who give less than 2% of the nonprofit’s total income (or from other public charities or the government).

One type of public charity is a community foundation, which typically focuses on supporting local charities in a specific geographic area. Community foundation revenues come from donations from individuals, families, businesses, and sometimes government grants. They offer grantmaking programs such as endowments, scholarships, and donor-advised funds (discussed below). Typical areas of support include education such as literacy programs, or human services, such as aid for the homeless.

Private foundations are generally established by an individual, family, or corporation and are overseen by a board of directors or trustees. Private foundations usually have to pay out at least 5% of their assets each year through grants or other charitable contributions.

An alternative to a private foundation is a donor-advised fund, a dedicated account for charitable contributions. In 2020, there were just over one million donor-advised fund accounts, with the average fund account size of just under $160,000. Annual contributions into these funds reached $47.85 billion. Donor-advised funds provide donors with immediate eligibility for a tax deduction for the year they contribute. However, the donor-advised fund is not required to make donations in any given year. A donor-advised fund allows the account owner to plan out their giving, focus the scope of their giving, and maintain anonymity if they so choose.

In this interview, Marie Ruzek, CFRE, Vice President of Philanthropic Services at Wells Fargo, explains the difference between a private foundation and a donor-advised fund.

Other 501(c)s

A 501(c) organization is an American tax-exempt nonprofit organization formed under Section 501(c) of the United States Internal Revenue Code and is one of over 29 types of nonprofit organizations exempt from some federal income taxes.

501(c)(4) organizations are characterized as “social welfare organizations.” These nonprofit organizations must “operate primarily to further the common good and general welfare of the people of the community.” They cannot benefit private shareholders or individuals. Unlike with 501(c)(3)s, donations to 501(c)(4)s are generally not tax deductible. 501(c)(4)s may also engage in political activities if that is not its primary activity. That means they spend less than 50% of their money on politics and advocacy. Several 501(c)3s have a 501(c)4 component that allows them to do advocacy work.

501(c)(5) organizations are labor, agricultural, or horticulture organizations, including unions. Like 501(c)(4)s, they may engage in lobbying activities and some political activities (such as supporting or opposing a candidate) as long as those are not its primary activities.

501(c)(6) organizations include business leagues, chambers of commerce, and trade associations. Activities must improve business conditions, though not any single business in particular. They may not engage in a regular business to make a profit. An example is the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. 501(c)(6)s may engage in political activities and lobbying but must notify members if dues are used.

Advocacy vs. Lobbying

Advocacy is ” ‘any action that speaks in favor of, recommends, argues for a cause, supports or defends, or pleads on behalf of others.'” In the nonprofit realm, advocating includes most forms of communication by a nonprofit. This includes conducting educational meetings or preparing educational materials on public policy issues.

Lobbying tends to be much more narrowly focused. According to the IRS, an organization engages in lobbying “if it contacts, or urges the public to contact, members or employees of a legislative body to propose, support, or oppose legislation, or if the organization advocates the adoption or rejection of legislation.”

This is the main difference between 501(c)(3) organizations and 501(c)(4)s, (c)(5)s, and (c)(6)s; 501(c)(3)s’ political involvement is limited to the advocacy of public policy issues, whereas 501(c)(4)s, (c)(5)s, and (c)(6)s may engage in legislative lobbying.

Nonprofit organizations can strengthen democracy by focusing on:

- Accountability and transparency in government;

- Initiatives that promote constitutional rights and principles;

- Fostering fair and honest election processes with organizations that engage in voter registration or poll worker training;

- Education and engagement outside of the election cycle that empowers individuals to participate in the policy-making process, like The Policy Circle;

- Building information ecosystems that inform the public about their representatives and opportunities to participate in civil life.

For example, The Bradley Foundation supports organizations (including The Policy Circle) that promote and protect founding principles and American exceptionalism. The Klarman Family Foundation focuses on rebuilding trust in news media by funding nonprofit journalism and advocating for press freedom. Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement’s Faith In/And Democracy focuses on how faith and faith communities support democracy and civic life. If a 501(c)(3) goes beyond such issues to influence actual legislation, it risks losing its tax-exempt status.

Funding for Nonprofits

Revenue for most 501(c)(3) charities comes from service fees (for example, many nonprofits offer memberships for a fee), government grants and contracts, foundation and corporate grants, events, and individual donations. Government grants and fees for services usually total about one-third of nonprofit sector revenue. Some organizations, such as The Policy Circle, are committed to operating without government support.

Corporate Giving

Corporate philanthropy “refers to the investments and activities a company voluntarily undertakes to responsibly manage and account for its impact on society.” This can include monetary donations and investments, donations of products and services, technical assistance, and employee volunteerism. Experts say corporations are more likely to give when the stock market is up, which explains the 6.1% decrease in corporate giving from 2019 to 2020.

Corporate giving programs are a specific form of corporate philanthropy driven by employee giving. The more employees donate to philanthropic organizations, the more their company will donate. For example, if an employee contributes their time or money, companies can match the gift or provide monetary grants to organizations where employees regularly volunteer.

Corporate philanthropy can help companies exhibit corporate social responsibility, a broad concept that “can help forge a stronger bond between employees and corporations, boost morale, and help both employees and employers feel more connected with the world around them.” This is especially important for companies as consumers begin to expect such actions from corporations. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer’s January 2021 survey, 68% of respondents believe CEOs should step in to fix societal problems when the government does not. In their 2022 survey, employees felt that CEOs should participate in policy discussions within their work, especially regarding the economy, technology, and wages. In 2021, corporate giving increased 23.8% from 2020 to $21.08 billion.

Individual Giving

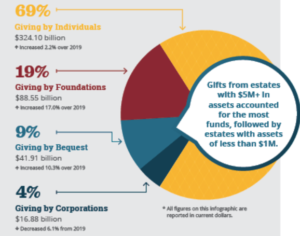

Compared to the number of donations from large entities like government, corporate, or foundation grants, individuals may not believe they make a substantial impact. However, the largest source of charitable giving was individuals: individual donors contributed $326.87 billion, or 67% of total giving. Charitable giving accounted for 2.3% of the U.S. GDP in 2020. Three-quarters of nonprofits surveyed by the Urban Institute say individual donations are essential. For smaller nonprofits, this is especially true. Organizations with an annual budget of under $500,000 make up over 60% of the nonprofits in Urban’s study. They report that 30% of their revenues come from individual donations (compared to 18% of revenue for larger organizations).

Nonprofit charitable organizations are not the only ones. According to the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, individual alumni donations in 2021 amounted to more than $12.25 billion of the nearly $53 billion colleges and universities raised from outside sources.

Individuals are more likely to give to causes they have an emotional or personal connection with. Particularly when it comes to giving locally, individuals give when they see the impacts of their donations and feel they contributed to their community’s benefit.

Melissa Kwee, CEO of the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Center, explains how any one individual can be a philanthropist (13 min):

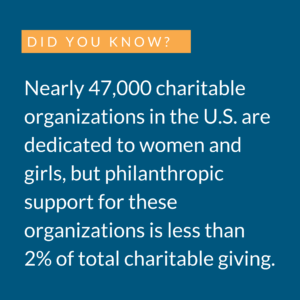

Women and Philanthropy

As individuals, women have had a substantial impact on charitable giving, notably as their labor force participation and earnings rose in the past several decades. In the U.S., women are the primary breadwinners in 40% of households with children, up from 15% in the 1970s. According to The Women’s Philanthropy Institute at Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, women are more likely to give than men across all income levels and generations. Compared to single men, single women of all ages are more likely to give, and give in higher amounts, to charity. Women are also more likely to give to charity after an increase in income than their male counterparts.

A 2020 study by The Women’s Philanthropy Institute found that women give nearly two-thirds of online donations on digital platforms and social media. They also tend to give to smaller organizations than their male counterparts, and roughly two-thirds of their charitable giving goes specifically to causes to support women and girls.

Women’s foundations and funds are primarily known for their grant programs but also focus on relationship building, partnerships, policy education, and advocacy. The programs vary and are geared towards different sects of the populations of women, such as age, marital status, education level, income, and employment or vocational status. Unsurprisingly, many women donors find that when they invest in other women, they also invest in children, families, and entire communities.

Giving Circles

Besides being more likely to give, women are more likely to give as a community; 70% of giving circles are majority women. A giving circle “is a philanthropic vehicle in which individual donors pool their money and other resources and decide together where to give them away.” Giving circles can empower community members and breed intentionality by allowing members to research and understand issues that impact their community and how to create meaningful change. Studies from the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University and the University of Nebraska Omaha found that giving circles give more and are more engaged in the community than donors not in giving circles. They give more strategically and to a broader array of organizations. Giving circles include the Latino Giving Circle Network, the Community Investment Network, and 100 Who Care Alliance.

FreeWill breaks down insights on trends shaping how women give (50 min):

Public Policies Impacting Philanthropy

Policies set by local, state, and federal governments influence neighborhoods, schools, healthcare, the environment, and the economy. It is no coincidence that these are all the most significant areas of philanthropic focus. Philanthropy can fill gaps left open or further support endeavors in these areas. By ensuring critical community institutions function well, citizens have better and more equal access to the processes and policies that shape their lives.

Tax Code Effects

In 2020, the most significant increase in charitable donations came from foundations. These entities contributed 19% of all donations, the largest portion ever from foundations. The growth is due to policy changes that loosened restrictions and allowed more flexibility to grantees during the pandemic. Other temporary measures include the CARES Act and Consolidated Appropriations Act (2021) allowances for an “above-the-line” deduction for charitable gifts of up to $300 for taxpayers filing separately and $600 for taxpayers filing jointly, even for those not itemizing.

Legislation makes more substantial and long-term changes to trends in charitable giving. Since 1917, the federal tax code has recognized the value of charitable giving, which has become a fundamental tenet of the income tax system by preventing people from being taxed on money they freely give away. To claim tax deductions, taxpayers must itemize their charitable contributions. Still, most taxpayers choose to claim the standard deduction because it is larger than the sum of their potential itemized deductions.

The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act doubled the standard deduction and eliminated some itemized deductions, prompting even more taxpayers to claim the standard deduction. This means their charitable donations do not provide a tax benefit, leaving many low- and middle-income households without a tax incentive to make charitable donations. The Tax Policy Center estimated that 21 million fewer households used the charitable giving incentive due to the changes. Studies of individual donors reveal declining participation rates. While donations increased, these donations have mostly come from fewer, wealthier donors. For more on the Tax Cut and Jobs Act, see The Policy Circle’s, Taxes Brief.

Besides the 2017 effects, the last genuinely foundational law regarding philanthropy passed in 1969 (it mandated a 5% minimum payout from private foundations). Recently, the Accelerate Charitable Efforts (ACE) Act, proposed over the summer of 2021, is gaining attention. Sponsored by Sens. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and Angus King of Maine, the legislation “would allow donors to get an upfront tax deduction for donor-advised-fund deposits if they distribute the money within 15 years.” Donors can still receive immediate capital gains, estate, and gift tax savings. It would also prevent foundations from meeting payout obligations by paying staff salaries or travel expenses and prevent donors from claiming tax benefits that significantly exceed the actual value of gifts. Some argue the distribution requirements may discourage charitable giving, while others maintain it is essential to make sure those resources are available for public use.

Donor Privacy

The First Amendment’s protections of free speech and free association include protections of anonymity in speech and association with organizations. In Alabama v. NAACP (1958), the United States Supreme Court recognized this right, which forbids the government from demanding organization member lists. Based on this right, donors (in most cases) are not required to disclose their support for an organization. However, courts often weigh these protections against competing interests in political activity cases, such as campaigns finance disclosure laws.

Federal law requires the IRS “to collect ‘the names and addresses of all substantial contributors,'” usually those who contribute over $5,000. Tax-exempt organizations must report these names to the IRS but are not usually required to disclose names publicly. Balancing this right to privacy “with the government’s legitimate interest in promoting transparency and investigating misconduct” resulted in significant litigation over the past decades.

The Supreme Court “upheld the right to distribute anonymous political leaflets” (McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission, 1995) and to “anonymously advocate door-to-door” (Watchtower Bible and Tract Society v. Village of Stratton, 2002). Most recently, in Americans for Prosperity v. Bonta (2021), the Supreme Court struck down a California requirement that charities and nonprofits provide the state attorney general’s office with the names and addresses of those who contributed $5,000 or more. The Court ruled that California’s alleged interest in preventing misconduct did not justify compelling charitable organizations to disclose major donors, which violated the First Amendment.

Some state laws, however, found limits on privacy. In Doe v. Reed (2010), the Supreme Court found that disclosing the names of petition signatories under a state open records law was not a violation of the First Amendment.

Donors may contribute anonymously for various reasons, “whether out of modesty, religious belief, fear of nagging phone calls, or…safety concerns.” The NAACP, in an amicus brief in support of the Americans for Prosperity Foundation, wrote:

“‘In an increasingly polarized country, where threats and harassment over the Internet and social media have become commonplace, speaking out on contentious issues creates a very real risk of harassment and intimidation by private citizens and by the government itself… it is necessary for individuals to be able to express and promote their viewpoints through associational affiliations without personally exposing themselves to a legal, personal, or political firestorm.'”

This idea became a point of contention, particularly in the political realm. Candidates, political parties, and political action committees must disclose expenditures, income, and donors, but 501(c)(3)s and 501(c)(4)s are not required to. Because 501(c)(4)s are allowed to participate in political activities, there is debate as to whether or not nonprofit organizations should be required to disclose donors.

Donor Intent

Donor intent “refers to how a person making a charitable contribution intends the money to be used.” Donors frequently value the opportunity to direct their gifts specifically.

There are two kinds of donations:

- The receiving organization may use unrestricted funds for any legal purpose.

- Restricted funds are set aside for a particular purpose and permanently restricted to that purpose, designated by the donor.

Federal and state laws protect donor intent, and donors have the right to sue organizations that do not use their gifts for the intended purpose.

When donor intent is a top priority, donors can structure their gifts to ensure their intent is carried out. One means is a gift agreement, a written agreement that states the specific purpose of the gift. It can go even further in some cases to include restrictions that would bar the funds from being used for purposes that may conflict with the donor’s values with an enforcement mechanism that creates consequences if the receiving organization does not comply with the agreement.

Donations to Political Campaigns

The First Amendment ensures the right to free speech; the right to contribute to political campaigns is considered an expression of this. Although donations to political campaigns are not tax-deductible, supporting candidates can be viewed as a component of a giving strategy since elected officials enact policies that impact citizens’ and companies’ behavior. Others argue that large contributions make politicians reliant on wealthy individuals and corporations, prioritizing the needs of these contributors above the needs of the average voter, thereby allowing them more influence to shape the outcomes of public elections and policy.

Concerns about potential corruption have sparked numerous pieces of legislation since the early 1900s, which resulted in the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 and the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002 to address spending and contribution limits and loopholes. The Supreme Court has worked to balance concerns about corruption in campaign financing without infringing on First Amendment rights. In 2010, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission found that “across-the-board bans on corporate or union expenditures are unconstitutional.” The Court held that “the rule that political speech cannot be limited based on a speaker’s wealth is a necessary consequence of the premise that the First Amendment generally prohibits the suppression of political speech based on the speaker’s identity.”

In McCutcheon v. FEC (2014), Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the court’s majority opinion, “[t]here is no right more basic in our democracy than the right to participate in electing our political leaders…We have made clear that Congress may not regulate contributions simply to reduce the amount of money in politics or to restrict the political participation of some in order to enhance the relative influence of others.”

For more on donor limits and other issues pertinent to campaign contributions, see The Policy Circle’s Campaign Finance Brief.

Conclusion

Strategic and intentional giving empowers individuals to impact their communities meaningfully and civically advance a cause according to their values and goals. Understanding the philanthropic landscape is key to an individual’s active and constructive civic participation.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

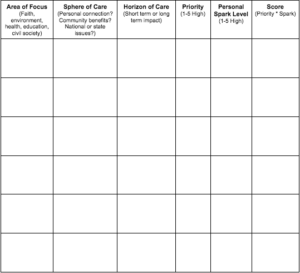

The following chart can help determine where and how to allocate your limited resources of time and treasures. Consider different areas of focus, such as civic engagement and economic empowerment. Spheres of care speak to where you are focused: on organizations that impact you and your community, international causes, or somewhere in between on the state or regional level. Horizon of care considers how your engagement looks down the line: is this something to address an immediate need, or are you able to engage in making a long-term impact?

Measure: Consider organizations you know of, have donated to, or are close to your community. Ask your trusted friends which organizations they support or volunteer with. Most importantly, do your research:

- What kinds of programs do they run?

- Are they rated on Guidestar?

- Run a simple internet search – are they in the news?

- Review the website and look at the organization’s history and current leadership.

- How does the organization measure impact? What are the stated outcomes? Is it clear that these programs are making a positive difference, and in what way?

- Do you know what they advocate or lobby for regarding public policies?

- Do they collaborate with other organizations?

- What is their budget?

- Do they disclose donors?

Identify: For the organizations:

- What are their sources of funding? What percentage comes from the government?

- Who are the beneficiaries of these programs?

- Do your local representatives know about the organizations that you support?

- Do you know how your representatives in Congress feel about donor privacy policies?

Reach out: Find allies and build community networks.

- Talk to community members to see their visions for the community and understand their concerns.

- Meet the leaders of your local community organizations

Plan: Set milestones, don’t try to do it all at once.

- Use the matrix above to define your focus and plan out your giving

Execute:

- Do your research:

- Look up the tax status of your favorite nonprofit organization. Are they a 501c3? Are they a private or public charity? Do they have a 501(c)(4) arm?

- Get involved in community initiatives.

- Listen and learn about the community, or contact the township to see important initiatives that are in place to understand major concerns.

- Consider creating an engagement scorecard – what are the main areas for concern, what’s being done, and is there room for beneficial involvement?

- Focus your giving engagement

- How and in what areas do you want to make an impact?

- Is this something that will have an immediate impact, such as volunteering at a soup kitchen, or long-term engagement, such as investing in research or coalition-building to address the root causes of a problem?

- On what level would you engage – local, state, national, or international?

- How much time, effort, and funding can realistically be allocated? Is this something you will contribute as an individual or as part of a group? Is there a champion who could lead the effort?

-

-

Additional Resources

- This chart from Fidelity Charitable breaks down donor-advised funds and private foundations.

- National Council of Nonprofits

- Giving Ventures, the DonorsTrust podcast, highlights nonprofit efforts, initiatives, and projects that leverage private philanthropy to solve public problems.

- Hear from individuals who have chosen to contribute through donor-advised Funds.

- General Rules Relating to Lobbying and Political Campaign Activities by IRC 501(c)(4), (c)(5), and (c)(6) Organizations

- See The Policy Circle’s policy briefs on Stitching the Fabric of Neighborhoods and Civic Engagement for more information and ways to get involved.