POLICY INSIGHT

Socialism: A Case Study on Venezuela

Podcasts

Listen to Trust Your Voice Podcast for an audio version of this Brief.

In addition, listen to Angela Braly, Co-founder of The Policy Circle, interviewing Emilio Pacheco, who was born and raised in Venezuela where he lived until 1987, about his experiences.

Audio Player

Introduction

This Case Study takes a closer look at Venezuela’s past and present social, political, and economic circumstances, the role socialist policies played, and how this relates to conversations within our government. Understanding the history of such an evolution is crucial to keeping similar tendencies from reaching other shores, including our own.

ON THE GROUND IN VENEZUELA

In what was once Latin America’s wealthiest nation, over 75% of Venezuelans are living in extreme poverty.According to a September 2021 report from the National Survey of Living Conditions, created in 2014 to make up for the absence of official data, the percentage of Venezuelans living in extreme poverty rose from 67.7% to 76.6%. This is a reversal of the improvement in previous years after the government started cash transfers and relaxed price controls. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the crisis in Venezuela that had been ongoing for years; before the pandemic, the UN World Food Programme estimated one-third of Venezuelans struggled to get enough food to meet the minimum nutritional requirements.

The U.S. State Department announced in September 2021 that it was sending $247 million in humanitarian assistance and $89 million in economic and development assistance to aid “Venezuelans in their home country and Venezuelan refugees, migrants, and their host communities in the region.”

This is in addition to $120 million from the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration; and $216 million through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), bringing total U.S. humanitarian, economic, development, and health assistance sent for the Venezuela crisis to more than $1.9 billion since 2017. This includes

- Food assistance;

- Emergency shelter;

- Access to health care, water, sanitation, and hygiene supplies;

- COVID-19 support;

- Protection for vulnerable groups, including women, children, and Indigenous people;

- Assistance to democratic actors within Venezuela;

- Integration support for communities that host Venezuelan refugees and migrants, “including development programs to expand access to education, vocational opportunities, and public services.”

WHY IT MATTERS

What separates Venezuela from similar nations is its history of centralizing power, government overreach, and inability to “stabilise external and fiscal accounts.” By imposing price controls, expropriating private property, and conducting large-scale industry nationalization, the Venezuelan government brought the economy to a standstill and eliminated the economic freedom of its citizens. The “dismantling of democratic checks and balances, and sheer incompetence” led to Venezuela’s collapse.

“Chavez’ so-called Bolivarian revolution took a peaceful, middle-income country and transformed it into a nightmare that puts the ruinous SOviet Union of the 1980s to shame.”

NOAH SMITH, BLOOMBERG

Some blame Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis on causes such as falling oil prices. However, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Kuwait are petro-states that saw their incomes fall when oil prices dropped but emerged from recession with their economies intact. Additionally, although President Maduro has blamed the U.S. and its imposed sanctions, none of these sanctions were broad enough to inflict the type of damage Venezuela is currently suffering.

The regimes of Presidents Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro decimated the country through “relentless class warfare and government intervention in the economy.” Maintaining basic freedoms and remaining committed “to the rule of law, limited government, and checks and balances” separates Venezuela from other politically and economically prosperous democratic countries and serves as a reminder of the dangers of socialism for the rest of the world.

Putting it in Context

OIL BOOM (1940s-1970s)

Geologists from Royal Dutch Shell struck oil in the northeast region of Venezuela in 1922. Annual production during the 1920s increased from about 1 million barrels to 137 million, putting Venezuela second only to the U.S. in total oil output.By the mid-1930s, oil totaled 90% of exports, pushing out all other economic sectors. However, foreign companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, controlled 98% of Venezuelan oil. In response, the Venezuelan government enacted a law in 1943 that required “foreign companies to give half of their oil profits to the state. Within five years, the government’s income had increased sixfold.”

Venezuela’s prominence in the oil market and government oversight of the industry was a constant throughout the 1940s and 1950s. In 1960, Venezuela became a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), through which the world’s largest oil producers coordinate prices to give states more control. Joining OPEC substantially benefited Venezuela during the 1970s, when an OPEC embargo during the Yom Kippur War caused oil prices to soar. Venezuela’s per capita income quickly became the highest of any country in Latin America as oil revenues quadrupled. In 1976, the President of Venezuela, Carlos Andrés Pérez, created the state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) to supervise the oil industry.

OIL BUST (1980s-2000s)

In the 1980s, global oil prices plummeted due to crude oil surpluses after the 1970s energy crisis. As Venezuela was almost entirely reliant on oil, the price crash brought Venezuela’s economy down. In 1989, President Perez implemented an austerity package as part of an International Monetary Fund bailout. Riots and strikes ensued, followed by an attempted coup by Hugo Chavez in the early 1990s. Although unsuccessful in his initial overthrow attempt, Chavez rose to fame and was elected president in 1998.

Once in power, Chavez raised oil income taxes on foreign companies in Venezuela. He promised to use the revenues to expand government-run welfare programs, hire more government workers, raise the minimum wage, and redistribute land.

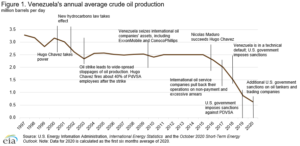

Meanwhile, the state-run oil industry faltered due to the government’s control structure. After a strike in 2002-2003, Chavez fired thousands of PDVSA workers and replaced them with loyal supporters with little technical and managerial expertise. Foreign investors and oil firms disliked the government interference, lost faith in PDVSA, and stopped operations.

COLLAPSE (2000s-PRESENT)

In the 2000s, President Chavez went on a nationalization spree to gain more control over the economy. This spree pushed out all private enterprises, starved industries of technical expertise and investment, and sent government-controlled institutions into a downward spiral. Exchange rate controls and price controls “broke the basic link between supply and demand, creating surreal economic distortions.” For more on supply and demand, markets, and price controls, see The Policy Circle’s Free Enterprise & Economic Freedom Brief.

This suffocated private enterprise. Price controls prevented private businesses from setting their own prices, making it nearly impossible to profit. Both foreign- and domestically-owned companies stopped investing in Venezuela, and new businesses did not replace them due to red tape, corruption, and fear that their private property was not secure. In 2011, Latin America received over $150 billion in foreign investment; Venezuela only accounted for $5 billion, while neighboring Brazil received $67 billion. Investment has declined further since then; in 2019, Brazil received $72 billion, Colombia $14 billion, and Chile $11 billion, while Venezuela received less than $1 billion.

Chavez garnered strong relationships with countries such as China, Russia, and Cuba to endure the inevitable disasters of his policies. He frequently announced new government programs to deliver free or heavily discounted goods that resulted from these relationships, such as refrigerators and cars, to the poorest in the nation. These efforts kept the worst-case scenario of Venezuela’s impending crisis at bay and also continuously won Chavez popular sentiment around election times. This stopped when Chavez died of cancer in 2013.

Chavez’s vice president, Nicolas Maduro, assumed the presidency in 2014, but this did not change the economy’s trajectory. Oil prices tumbled, and inflation reached over 50 percent, prompting Maduro to cut public spending. By mid-2016, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans were protesting. Maduro’s response was to crack down on dissent.

For more on Venezuela’s history, Hugo Chavez, and Nicolás Maduro, watch The Collapse of Venezuela, Explained (8 min).

The Role of Government

Venezuela’s situation was the product of years of government policies and economic mismanagement. The clear signs of trouble came from a charismatic leader who promised the nation that the government was the solution to their woes and made the country dependent on one resource while shutting down competition, diversity of opinion, and debate. Drastic changes often happen in the slow erosion of democratic protections.

BOLIVARIAN REVOLUTION

Chavez sympathized with the Venezuelans who suffered under the IMF-backed austerity measures during the late 1980sand mid-1990s. His campaign promise was to use his power to distribute public and private oil revenues to people experiencing poverty. Chavez spent these funds on social services and welfare programs. The social programs, called “misiones,” delivered essential services for education, health, employment, and food. There was practically no limit to these welfare programs; in one year, the government handouts included approximately 200,000 homes.

This “Bolivarian Revolution” initially improved a number of social indicators such as literacy, income per capita, unemployment rates, and infant mortality. Between 1999 and 2011, Venezuela’s Gini coefficient (a measure of income inequality) fell from almost .5 to .39, meaning Venezuela at the time had the “fairest income distribution” in all of Latin America and ranked just ahead of the U.S. and only behind Canada in the Western Hemisphere. Between 2003 and 2013, poverty levels fell from 61% of the population to 34%.

NATIONALIZATION

Chavez’s economic model intended to have community enterprises working alongside the private sector, but government overreach meant national agencies, co-ops, and state industries comprised the bulk of the economy. Starting in 2007, the government used oil revenue to buy the largest electricity and telecommunications companies. It also seized the largest agricultural supplies company, steel producer, glass producer, and three largest cement industries.

These produced little return, and co-ops, in particular, often “wound up in the hands of incompetent and corrupt political cronies.” Additionally, private enterprises suffered several state-imposed regulations and high taxes. International airlinesstopped servicing flights to Venezuela, and businesses, including General Motors, Clorox, and Kellogg’s, fled the inhospitable economic conditions due to the risk of having their assets taken by the state. The World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 report listed Venezuela as one of the worst countries in which to do business, ranking it 188th out of 190 countries. It will update its Venezuela data in 2026.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH

Government oversight of the media and efforts to stop coverage of the opposition has escalated in recent years. The government has threatened news outlets that cover opposition, shut down radio stations, raided television channel offices, and blocked websites. Several international journalists have been arrested and deported; even veteran Univision News anchor Jorge Ramos was detained during an interview with President Maduro. In May 2021, government forces seized the newspaper’s headquarters, El Nacional, after the Supreme Court ordered it to pay defamation damages (the Supreme Court has been accused of lacking judicial independence). Additionally, since the COVID-19 state of emergency was enacted, many people have been charged after sharing or publishing information on social media that questions officials or policies.

Freedom House, an international organization that analyzes challenges to freedom, ranks Venezuela as “not free” regarding political rights and civil liberties.

Article 57 of Venezuela’s 1999 constitution guarantees freedom of expression, and Article 51 guarantees the right to access public information. However, the 2004 Law on Social Responsibility in Radio, Television, and Electronic Media bans any content that could “‘incite or promote hatred,’” or “’ disrespect authorities.’” As in other authoritarian countries, in Venezuela, there is no protection for either citizens or the media to speak out against the government.

SUPPRESSION OF OPPOSITION

Venezuelan security forces routinely use tear gas and rubber bullets to suppress protesters. In 2016, Maduro responded to massive demonstrations involving over 6 million Venezuelans by banning street protests, which led to over 130 deaths and almost 5,000 arrests. In 2017, United Nations Human Rights officials were not allowed into the country during an investigation of over 120 deaths that could have been related to government forces.

Many protests have been in response to government attempts to consolidate power. In 2015, the opposition party gained a two-thirds majority in Venezuela’s congress, the National Assembly. President Maduro then stripped the congress of its constitutional powers and replaced it with a Constituent Assembly packed with legislators loyal to Maduro’s regime. Maduro also declared the assembly’s Supreme Court appointments illegal and replaced the Supreme Court with a parallel Supreme Tribunal of Justice, packed with new magistrates that Maduro trusted.

Protests continued in 2024 (see below for more on the 2024 elections).

FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS?

Suspicious activity surrounded the 2018 Venezuelan presidential election. In the months leading up to the election, Maduro blocked opposition parties from participating or campaigning and arrested opposition candidates.

After voting, many people visited “Red Spots,” pro-government booths where they could receive government-subsidized food boxes and give “their names to workers who were keeping lists of those who had voted.” Although workers claimed there was no effort to “link a pro-Maduro vote to future food deliveries,” one woman said she felt “compelled to vote for Mr. Maduro” and feared losing her government job if she did not give her name at the Red Spot.

The results revealed Maduro had received 5.8 million votes (for comparison, he received 7.5 million votes in the 2013 election after Chavez’s death). His main rival, Henri Falcón, who ran despite fellow opposition members calling for an election boycott, received 1.8 million votes. Maduro claimed victory, but Observación Ciudadana (Citizen Observation) and several international organizations denounced the results, listing cases of coercion, intimidation, and the fact that only 46% of Venezuelans voted on election day. For the three previous presidential elections in 2006, 2012, and 2013, between 70 and 80 percent of the population voted.

To understand more about how Venezuela’s 2018 elections violated Venezuelan Law and internationally recognized standards, look at this pamphlet.

Suspicious activity also surrounded the most recent election, held in July 2024. The government named Maduro the winner, yet allegations were reported of 1,000 opposition leaders jailed, a prominent opposition leader kidnapped, and protests of people calling the election fraudulent. Maduro’s government declared he won with 51.2% of votes, and Eduardo Gonzales (his opponent) received 44.2%. However, the opposition claims that Gonzalez won, receiving 6 million votes to Maduro’s 2.7 million. Just days after the election, in August 2024, the U.S. government recognized Gonzalez as the winner, as did other EU countries.

Tensions in Venezuela remained high throughout the summer. In September 2024, Gonzales fled to Spain after reporting he was “forced to sign” a letter recognizing Maduro as the victor.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

THE OIL CURSE

How did the nation home to the world’s largest oil reserves find itself in its current situation, so different from that of Saudi Arabia, which has the second largest oil reserves? According to political scientist Michael Ross, part of Venezuela’s crisis stems from becoming dependent on its most abundant resource: oil.

Using oil revenues for social change continuously deepened the dependence on the resource. There was little concern when oil prices were high in the mid-2000s, but prices fell in 2014, and Venezuela no longer has the funds to import what it does not produce at home. Chavez “did little to improve how Venezuela actually makes money. He paid no attention to diversifying the economy in domestic production outside of the oil sector.” Instead of relying on an entrepreneurial economy to produce various goods and services to generate wealth, Chavez’s policies, continued by Maduro, made citizens dependent on one commodity.

PRODUCTION

Many Venezuelans were initially excited when Chavez rose to power. But not all has gone according to plan; the country’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) has plummeted since 2012, and the International Monetary Fund estimates Venezuela’s GDP is around $50 billion (neighboring Colombia’s GDP is over $350 billion, and the United State’s is over $24 trillion). Domestic production plunged, and food imports soared; according to the director of Venezuela’s Confederation of Associations of Agricultural Producers, Venezuela went from producing 70% of its food to importing 70%. All materials, from seeds to fertilizer, are provided by the government, but farmers report they often do not receive supplies. Additionally, the government-controlled steel industry does not produce enough machinery, and inflation has made it almost impossible to afford to import new equipment. Production hit an all-time low in 2019.

INFLATION AND HUNGER

Oil revenues allowed Venezuela to import goods from abroad, but when oil revenues declined, Venezuela could no longer import the goods it did not produce. The scarcity of goods drove prices up, resulting in massive inflation. The price controls under President Chavez made necessities more affordable, but it was no longer profitable for businesses to make them. As a result, people were forced to turn to the government for handouts or the black market.

In 2016, Maduro started a government food handout program called CLAP Boxes. By 2018, the government had made cuts to various welfare programs, including the CLAP program. One researcher at the University of Venezuela claimed the boxes supplied about half of Venezuelans’ food requirements and noted that the boxes dropped from 16 kilograms in January to 11 kilograms in May. In 2019, evidence of corruption by those seeking to profit from the poverty program was widespread, bringing little help to Venezuelans in need.

President Maduro repeatedly increased the minimum wage in an attempt to combat inflation. In August of 2018, a 3000% increase equated to about $20 a month. This had almost no effect; nearly 90% of Venezuela’s population lived in poverty, and prices were doubling every 19 days, on average, by the end of 2018.

Over the summer of 2019, the Maduro regime scaled back on price controls, printing money, minimum wage increases, and regulating importers and businesses. Inflation has fallen from over 1 million percent in mid-2018 to 2,500% in late 2021 to about 500% in mid-2022. The massive emigration of Venezuelans has also boosted the economy since those who fled send remittances back home in the form of dollars, which retailers in large cities like Caracas are now accepting. By one estimate, two-thirds of all transactions in Venezuela occur in foreign currencies, mainly the U.S. dollar. Despite the drop, inflation is still sky-high (see the $15 cereals), most Venezuelans still depend on nearly worthless bolivars, and the national minimum wage equates to less than $2 per month. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the situation, as the number of Venezuelans living in extreme poverty spiked by 10%.

Hyperinflation in Venezuela has continued to worsen since the pandemic. In July 2023, annualized inflation was 439%, the highest in the world. Although the average monthly income in Venezuela rose to $161 (U.S. Dollar) in 2023, that only covers 32% of the cost of the basic food basket.

“The cost of a basic food basket—an indicator which tracks staple food prices over time to measure inflation—increased by nearly 350 percent between October 2022 and October 2023.” (USAID, March 6, 2024).

EDUCATION

As the economy crumbled, education became a luxury. Students attended school primarily to receive state-sponsored meals, but the buildings lacked water and electricity. At the start of the school year, thousands of teachers did not show up to classes, having opted for different jobs that earn slightly more money or trying their luck abroad. Similar to brain drain during war, long-term economic hardship drives educated workers to more prosperous areas with more opportunities. This video from the Washington Post illustrates the enrollment and staffing troubles in the country that were prevalent before COVID-19. UNICEF reported 6.9 million students in Venezuela missed almost all classroom instruction between March 2020 and February 2021.

Post-secondary education is also suffering. Simon Bolivar University, dubbed Venezuela’s “University of the Future,” has been government-funded since it opened in 1970. Still, alumni living abroad have been financing the university with private donations and teaching classes via Skype. Professors can only expect to earn the equivalent of $25 per month, prompting many to flee the country. Over 430 faculty and staff members left the university between 2015 and 2017.

A news report in July 2023 details the continued decline, calling Venezuela’s education system “on the brink of collapse.”More students and teachers drop out of the system each year, and those who continue to attend school only go two or three days a week.

HEALTHCARE

Education is not the only sector experiencing brain drain; over 20,000 doctors have fled Venezuela’s inhospitable conditions since 2014. Medical professionals have been attacked by patients’ relatives, frustrated by the supply shortage and machine and infrastructure failures ranging from power outages to water shortages. Across the country, hospitals face shortages of essential medicines such as those to control hypertension or diabetes, and high-cost drugs for cancer, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis are no longer imported. Organ donations and transplants stopped in 2017.

The 1996 Constitution guaranteed the right to health as “an obligation of the State,” However, the State has reduced funding, silenced practitioners, and censored health system publications. The government spends about 1.5% of GDP on healthcare, 75% lower than the world standard.

In 2015, Venezuela’s Health Ministry “stopped publishing weekly updates on relevant health indicators.” When health minister Antonieta Caporale briefly resumed updates in 2017, she was immediately fired. The statistics revealed that between 2016 and 2017, maternal mortality rose 65%, and infant mortality rose 30%. Tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, and malaria are also creating emergency situations, and disease is accompanied by widespread malnutrition. According to WHO standards, malnutrition among children under the age of 5 in Venezuela has reached a “crisis level.” A university study found that, on average, almost two-thirds of Venezuelans surveyed lost about 25 pounds in 2017. (Human Rights Watch, CEPAZ). Venezuelans called this the “Maduro Diet.”

The situation did not improve during the COVID-19 pandemic; Monitor Salud, an NGO, reported that 83% of hospitals have insufficient or no access to personal protective equipment, and 95% lack sufficient cleaning supplies. Estimates indicate only about a quarter of the population is fully vaccinated.

Access to healthcare has only worsened since the pandemic. In August 2023, over 72% of Venezuelans were unable to access public health services when needed, compared to 65.5% in July 2021.

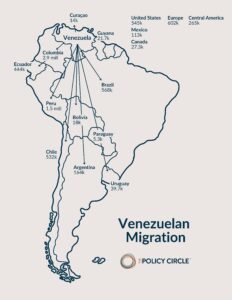

REFUGEE CRISIS

Venezuela is now the origin of one of the largest mass migrations ever on the Latin American continent. As of 2024, almost 8 million people, 20% of the population, have fled Venezuela due to food, water, and medicine shortages. More are expected to leave the country following the 2024 presidential election turmoil.

Colombia, Venezuela’s neighbor to the west, absorbs most of those fleeing. However, Colombia closed the border with Venezuela to try to stem the spread of the coronavirus; in February 2021, Colombia’s President Iván Duque announced the government would “provide temporary legal status to the more than 1.7 million Venezuelan migrants who have fled to Colombia in recent years.” Hundreds of thousands more pass through Colombia on their way to other countries, including Peru, Chile, and Ecuador. Venezuelans now need a passport or visa to travel to other Latin American countries when they previously only needed national identity cards. This adds insult to injury as passports are challenging to obtain given “paper shortages and a dysfunctional bureaucracy.”

See more about how Colombia is handling this refugee crisis here (9 min):

INFRASTRUCTURE

Intermittent power outages are a regular occurrence, but a massive outage that affected 22 of Venezuela’s 23 states in early March 2019 revealed the severity of the state of Venezuela’s energy infrastructure. Pro-government officials blamed Venezuela’s opposition party, claiming they had sabotaged Venezuela’s hydroelectric Guri Dam as part of an “electricity war” directed by the U.S. Energy experts and power sector contractors. Employees from the government energy company attributed the problems to “years of underinvestment, corruption, and brain drain.” Skilled operators “had long left the company because of meager wages and an atmosphere of paranoia.”

The fallout has only exacerbated the suffering of the Venezuelan people. Looters started ransacking businesses for food and supplies. Gas stations could not pump fuel, causing many to turn to the black market for gasoline in “a country that subsidizes fuel to the point that it is nearly free.” According to Julio Castro of the organization Doctors for Health, at least 20 people died in public hospitals due to the outages; damaged or drained backup generators could not keep machines required for dialysis, incubators, and artificial ventilation running.

These photos from The Guardian illustrate the effect of the 2019 blackout in Caracas. By 2024, power blackouts had become a way of life.

AID

During the first week of February 2019, international aid reached the Colombian and Brazilian borders. President Maduro ordered troops to barricade bridges at the borders to prevent aid from entering. Over 300 low-ranking soldiers fled their posts that weekend, but they were a small fraction of the 200,000 troops that remained loyal to Maduro and refused to let the trucks filled with food and medicine cross the border. Listen to this NY Times podcast on the humanitarian aid debacle in February 2019.

Maduro repeatedly denied the extent of the crisis in Venezuela and said any aid efforts from the U.S. or other countries were “part of a hostile foreign military intervention.” At the end of March 2019, however, Maduro reached an agreement with the International Red Cross to deliver aid. The first shipment reached Venezuela in mid-April. By September 2019, the aid was only making minor improvements, and the shortage of medicines persisted. Over the summer of 2020, Venezuela’s opposition party reached an aid agreement with the Pan American Health Organization, specifically to help Venezuela respond to the pandemic, but Human Rights Watch reported in December 2020 that Venezuelan authorities were “freezing bank accounts, issuing arrest warrants, and raiding offices” of humanitarian groups operating in the country.

Charitable organizations such as the Red Cross have helped facilitate aid not only to those in Venezuela but also to refugee support in nearby Latin American countries. The United States alone allocated $140,417,967 in Fiscal Year 2023 for such aid.

INTERNATIONAL ENTANGLEMENT

Despite the controversy surrounding the 2018 election, Mexico, Turkey, Iran, Bolivia, Nicaragua, China, and Russia continued to recognize the Maduro regime. China, in particular, offered technical assistance to help restore the country’s electrical grid. Additionally, China and Russia vetoed a United Nations Security Council vote in February to condemn the May 2018 elections and call for international humanitarian aid for Venezuela.

Russia and Venezuela have a long history in the oil industry. Since 2015, the Russian state-controlled oil firm Rosneft has increased its loans to Venezuela and its shareholder stakes in a joint venture with PDVSA. A Reuters investigationuncovered documents revealing that equipment is scarce, oil output is far lower than projected, and a “$700 million hole in the balance sheet of the joint venture.” Still, Venezuela buys Russian weapons, which gives Russia an incentive to stand by its ally and even provide military support. However, “Russian banks, grain exporters, and even weapons manufacturers have all curtailed business with Venezuela.”

Cuba is also heavily involved with Venezuela’s oil industry. In the early 2000s, Cuban leader Fidel Castro signed a deal with Hugo Chavez to provide Cuba with crude oil in exchange for Cuban professional staff and intelligence and security agents to go to Venezuela. Venezuela’s oil production has collapsed, and Cuba gets far less oil than the agreement states, but Cuba’s reliance on Venezuelan oil and the countries’ long-standing allegiances to one another are incentives to support the Maduro regime. The opposition has criticized this longstanding agreement.

CITGO

In 1986, Petróleos de Venezuela, or PDVSA, purchased 50% shares in Texas-based Citgo, and in 1990, PDVSA purchased it outright. Citgo is the seventh-largest refiner in the U.S. as of 2023.

Juan Guaidó was serving as the head of the National Assembly and opposition party following the corrupt 2018 elections.In January 2019, Guaido claimed the presidency with the support of the National Assembly and that of many world leaders, including the United States.

Amid this power struggle, tensions rose around Citgo. The Citgo business relationship has been strained, especially after Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s PDVSA “so that any new profits would be deposited in an account under Guaidó’s authority.” However, the administration has yet to figure out how to disburse these funds to Guaidó. In 2019, this became a serious problem for Guaidó, whose National Assembly would need to make a $913 million payment to PDVSA bondholders to maintain control of Citgo. In 2022, Guaido’s government was dissolved, leaving control of the PDVSA unclear.

The future of PDVSA’s control of Citgo continues to be in jeopardy. In October 2023, a U.S. District Court ordered PDV Holding to repay up to $21.3 billion in claims against Venezuela and PDVSA for expropriations and debt defaults. A court-ordered auction of PDVSA’s shares has been underway throughout 2024.

The Future of Venezuela

OPPOSITION UPRISING

Despite the international community’s condemnation of the 2018 elections, Maduro began his six-year term with an inauguration ceremony on January 10, 2019. Barely two weeks later, mass demonstrations broke out in Caracas in support of Guaidó, who was then serving as head of the National Assembly. Given the contested election results, Guaidó claimed Maduro was usurping the presidency by staying in office and that Guaidó could assume power based on Article 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution, which states: “If at the outset of a new term, there is no elected head of state, power is vested in the president of the National Assembly until free and transparent elections take place.” He swore himself in as interim president on January 23, 2019. After a few years of an interim government led by Guaidó, the National Assembly voted to dissolve his government in 2022. It established a new commission in hopes of unifying to defeat Maduro in the 2024 election.

The 2024 election brought more unrest. On July 28, 2024, Maduro again claimed victory over the opposition’s candidate, Eduardo Gonzales, under contested results. After protests, Gonzales was forced into exile and fled to Spain in September. With independent election experts claiming evidence that Maduro did lose the election, Gonzales is reporting his intent to return to Venezuela and set up a new government in January 2025.

While opposition to Maduro’s government persists, the absence of basic democratic foundations and free elections has kept Maduro in power. International pressure continues to mount.

PRESSURE FROM ABROAD

Following the 2018 and 2024 elections, the U.S. and EU leaders recognized opposition leaders as the rightful winners. However, Maduro has refused to relent and give up power.

In 2019, the U.S. recognized Guaidó as the leader of Venezuela, which prompted a series of U.S. sanctions against the Maduro regime. In August 2019, these sanctions turned into a total economic embargo. Most of Europe called for re-elections by the end of January. Spain, Britain, France, and Germany endorsed Guaidó after Maduro refused to hold elections again. At the end of January 2019, European Union lawmakers voted 439 in favor to 104 against (with 88 abstentions) to recognize Guaidó until “new free, transparent and credible presidential elections” occur. The EU parliament has no foreign policy powers but has symbolic importance, especially in human rights. In the realm of human rights, the International Criminal Court prosecutor announced in November 2021 the decision to open an investigation into possible crimes against humanity committed in Venezuela.

Maduro severed diplomatic relations with the U.S. For more on the tense relationship that ensued between the U.S. and Venezuela and how it’s affecting conditions right now, check out this BBC video.

Violence and political stalemate continued throughout 2019. Peace talks between the two sides did little to reach a compromise. In January 2021, the opposition party boycotted national elections, which means technically, Gauidó’s term as congressional speaker expired. Many Latin American and European nations have “distanced themselves” from the opposition as they cannot justify “recognizing a leader who has no control over the country.” The U.S. withdrew support for Guaido’s government in January 2023, following the Assembly’s dissolution of Guaido’s interim government in December 2022.

Tensions are worsening between the world leaders and Maduro’s government following the July 2024 elections. In September, the U.S. imposed sanctions on 16 Maduro allies for obstructing the election and joined 30 countries in issuing a statement expressing concern about Venezuela’s lack of respect for democratic principles and human rights. The EU passed a resolution recognizing Gonzales as the rightful president-elect.

Venezuela’s crisis shows no signs of improving. As governments and factions compete for power, the people of Venezuela continue to suffer.

What You Can Do to Get Involved

- Be in the know on Venezuela issues and share with your friends, colleagues, and family:

- Check out The Policy Circle Brief on Free Enterprise & Economic Freedo, or It’s a Wonderful Loaf from Russ Roberts at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution for more on markets and how they are affected by government interference.

- Listen to The Policy Circle’s Conversation Call about Venezuela.

- Keep track of bills in Congress related to Venezuela.

- Engage

- Apply for The Policy Circle’s CLER Program to join a community of like-minded women learning better skills to be effective business and civic leaders in their communities.

- Know who decides policy in Venezuela: Stay up to date with information from the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

- Organize a community gathering about aid, policy, and what your tax dollars will support in foreign countries.

- Pose any questions in a written piece for your local publication to make others in your community aware and seek answers.

Newest Policy Circle Briefs

Assessing Candidates Guide

The First-Time Voter Handbook

Women and Economic Freedom

About the policy Circle

The Policy Circle is a nonpartisan, national 501(c)(3) that informs, equips, and connects women to be more impactful citizens.