POLICY CIRCLE BRIEF

Affirmative Action

Introduction

Policymakers, jurists, businesses, and academia have grappled with the concept of affirmative action for decades. The original goal of affirmative action was to create a more level playing field for individuals from underrepresented groups in education and employment. Affirmative action continues to spark contentious debates regarding its legality, fairness, and effectiveness. Critics, like Manhattan Institute Fellow and Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley, contend that affirmative action deviated from its “original intent of equal opportunity and morphed into racial preferences” that, he said, “ diminish individual achievement” and “allow others to take credit for black accomplishments. They falsely imply that black upward mobility can’t or won’t occur without officially sanctioned favoritism.”

With a landmark ruling of 6-2 in the Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and a ruling of 6-3 in Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, the Supreme Court rejected the use of race in college admissions processes. New questions continue to emerge about how American society should function as it relates to race-based factors. Proponents of affirmative action consider this ruling a step in the wrong direction. “It feels tragic,” said Columbia University President Lee Bollinger. “It feels like the country has been on a course of choosing between a continuation of the great era of civil rights and another view of ‘We’ve done this long enough, and we need a whole new approach.’ It’s now the second choice.” Although prior Court decisions have traditionally linked affirmative action to college admissions processes, race-based and race-conscious policies reach far beyond employment, career advancement, access to resources, and government services.

The Policy Circle Brief provides an overview of how affirmative action has been implemented, its impact, and the implications of the Supreme Court ruling beyond academia.

CASE STUDY

Granderson Hale was a top graduate of his Philadelphia high school in 1968 and was accepted with a full scholarship to Wesleyan University in Connecticut. Hale says he sympathizes with those who want the end of race-conscious admissions. Hale credits his education, which included an M.B.A. from the Wharton School, as a component of his success, but said he “would prefer to see investments in early education for Black and Hispanic students, who often attend low-performing K-12 schools.”

Hale said that affirmative action led to many of his Black colleagues being regarded as less qualified. “People don’t respect you if they have to let you in,” he said. Contrast Hale’s experience and perspective to a Pew Study that shows Black adults express more support than opposition to affirmative action practices, with 47% approving and 29% disapproving. About a quarter of Black adults (24%) say they are not sure.

Conversely, a neuropsychologist at Columbia and a 1991 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, Jennifer J. Manly, was not bothered by the fact that affirmative action had given her an advantage in admission. “I never felt guilty about that, because I was going to have to prove myself,” she said.

WHY IT MATTERS

Affirmative action refers to policies and measures implemented to address historical and ongoing discrimination and promote equal opportunities for underrepresented groups, particularly in employment and education. The aim is to actively counteract the effects of past and present discrimination based on factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, or disability.

The concept of affirmative action gained prominence in the United States during the 1960s as part of the broader civil rights movement. President John F. Kennedy first introduced the term in an executive order in 1961, instructing government contractors to take affirmative action to ensure equal opportunity in employment. However, it was under President Lyndon B. Johnson that affirmative action was expanded and more explicitly connected to promoting racial equality.

Over the last seven decades, affirmative action policies morphed and were extended into other sectors, such as education, business, and social services.

The topic of affirmative action will continue to generate debate, and legal challenges will abound after the Supreme Court’s ruling. There will be implications beyond admissions and we will see changes in how race is factored into employment decisions, contracting, and investing (ESG) practices.

Equal access to education and the opportunities a quality education provides are key components to success. Understanding affirmative action is important in order to analyze and better address ways to mitigate inequalities without discriminating. Check out The Policy Circle’s Education Innovation, Literacy, Education Savings Accounts, and Education K-12 Briefs to learn more about these areas.

HISTORIC RULING

In a historic June 29, 2023 ruling, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) addressed two separate lawsuits filed by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, contending that race-based admissions violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. You can read the Supreme Court’s majority opinion and dissents here.

“For ‘[t]he guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one thing when applied to one individual and something else when applied to a person of another color.’”

CITING REGENTS OF UNIV. OF CALIFORNIA V. BAKKE, 438 U. S. 265, 289-290

Chief Justice Roberts drafted the opinion which states that “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.” The Court held that the Equal Protection Clause should be universal in its application without any regard to differences in race.

If people are to be treated differently, there is an exception to the Equal Protection Clause’s guarantee, but it is not easy to meet. Strict scrutiny is a daunting two-part test where the party seeking an exception has to show that (1) the racial classification will “further compelling governmental interests” and (2) that the government’s use of race is “narrowly tailored,” i.e., “necessary,” to achieve that interest. Further, in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U. S. 306, the Court imposed one final limit on race-based admissions programs: At some point, they must end. Id., at 342. The Court held that neither Harvard nor UNC had shown their admissions policies met the strict scrutiny tests.

Further, Roberts opined that “twenty years have passed since Grutter, with no end to race-based college admissions in sight.” The opinion holds that Harvard and UNC failed each of these strict scrutiny criteria and, therefore, their race-based admission practices are invalid under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Justices Sotomayor and Jackson wrote dissents asserting that education is a means of success in the country and that Court precedent protected the consideration of race in admissions. To the dissent, equal protection under the law means the government must have a vested interest in the integration of schools. Sotomayor wrote, “The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society.”

Justice Jackson asserted, “With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, today, the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

In the dissent, Justice Jackson discussed alternative routes universities could take by considering applicant information such as socio-economic status, which could cause further confusion regarding which factors universities are allowed to consider.

The impact of this decision will continue to unfold, but the leadership of SFAA plans to pursue litigation to end race-based practices related to employment diversity programs, corporate board diversity quotas, and government contracting requirements.

The History of Affirmative Action

1960s & 70s: A series of executive orders mandated government contracts to take affirmative action to not only treat employees equally concerning their race, creed, color, or national origin, but under Lyndon B. Johnson, to increase opportunities for minority groups. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. In 1964, The Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) was established. In Bakke v. University of California, the Supreme Court ruled that while rigid racial quotas are unconstitutional, race can be considered as a factor in admissions decisions to achieve diversity.

1990s & early 2000s: The Supreme Court ruled in Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña that all racial classifications by the government must be subject to strict scrutiny, and in Grutter v. Bollinger, that race can be considered as one of many factors to achieve a diverse student body. In Gratz v. Bollinger, the Court struck down the University of Michigan’s undergraduate admissions policy that awarded points based on race, deeming it too “mechanistic.” Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which strengthened the previous law, particularly regarding the liability on employers and the burden of proof.

2013 – 2016: In Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (Fisher I), the Court sent the case back to the lower courts, stating that affirmative action policies must meet the strict scrutiny standard and that the courts should closely examine whether the University of Texas’s admissions process was narrowly tailored to achieve diversity. Then, in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (Fisher II), the Court upheld UT’s affirmative action program, affirming that race-conscious admissions policies as constitutional so long as they are narrowly tailored and meet the standards of strict scrutiny.

Public Opinion

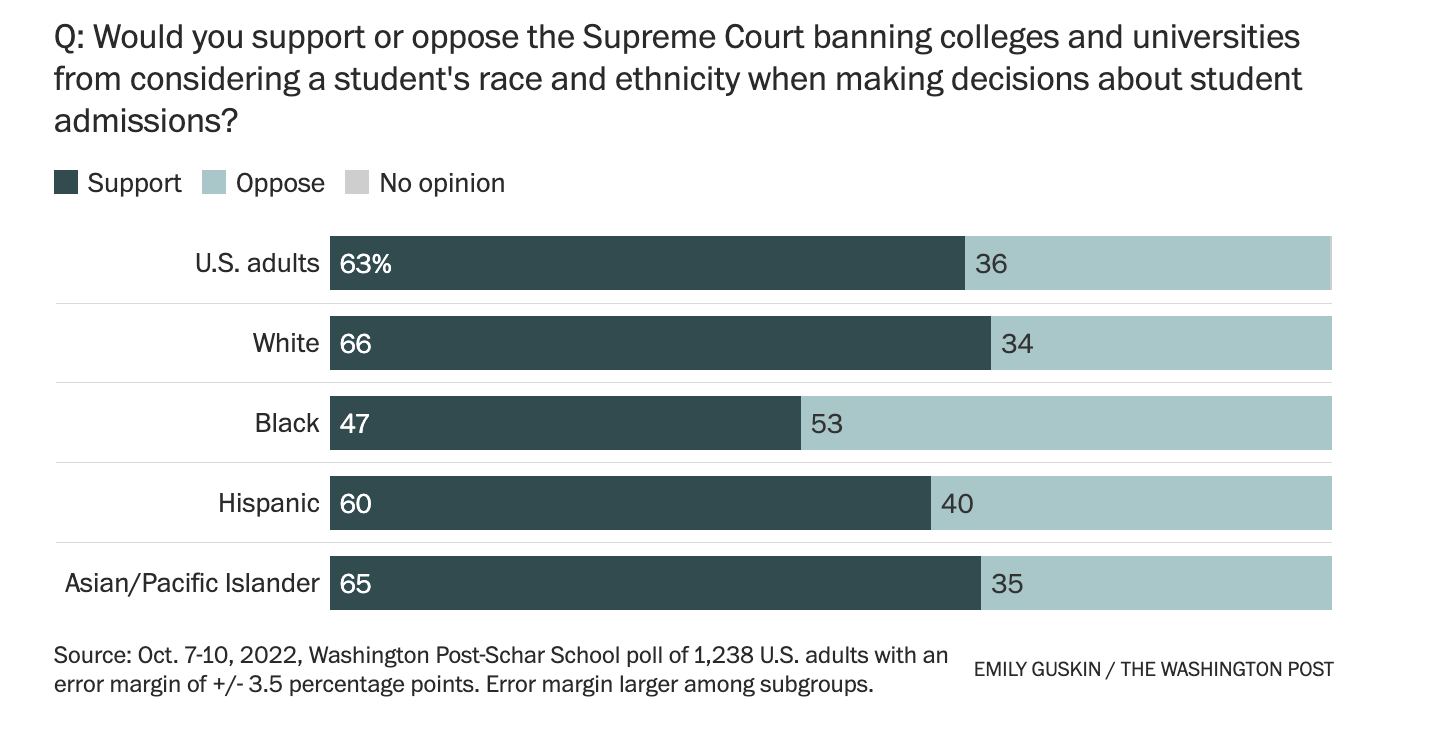

The Washington Post-Schar School Poll recently shared that 63% of U.S. adults support leaving race out of college admissions processes.

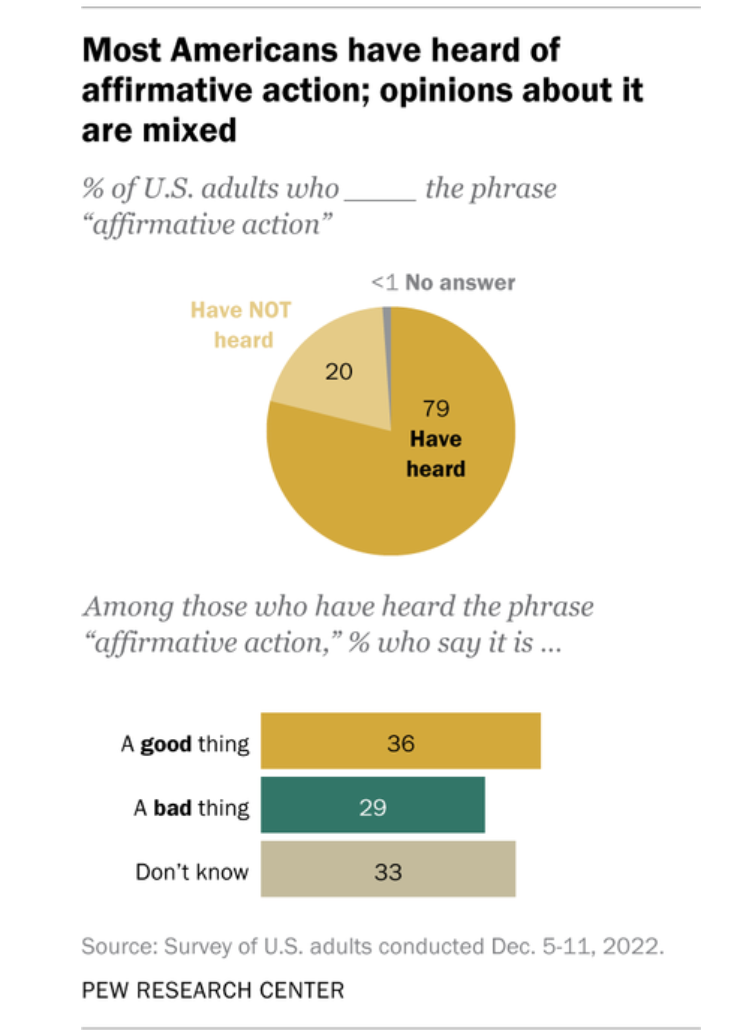

However, according to a December 2022 Pew Research Center Survey, of the participants that recognized the phrase affirmative action (79%), only 29% said it is a bad thing. The resulting opinions remain mixed. These conflicting surveys demonstrate, alongside many other public opinion polls, “the turbulent crosscurrents of public opinion on affirmative action.”

The resulting opinions remain mixed. These conflicting surveys demonstrate, alongside many other public opinion polls, “the turbulent crosscurrents of public opinion on affirmative action.”

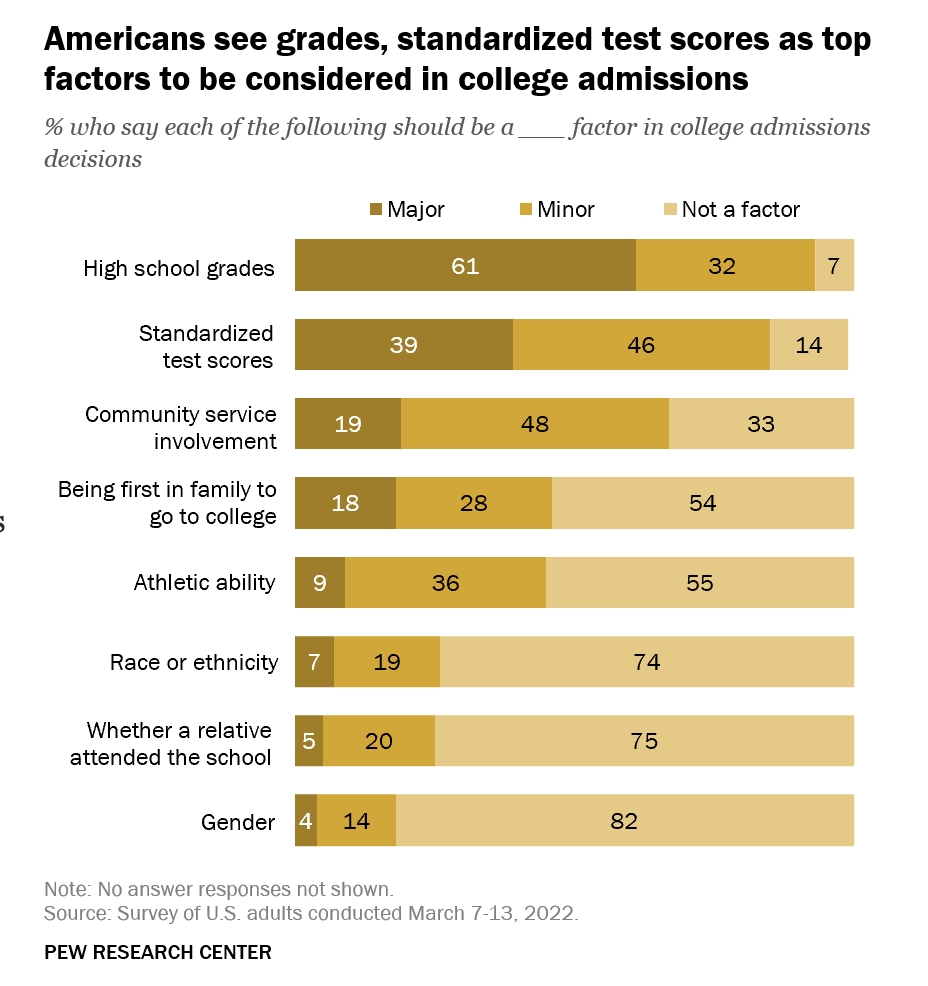

Further, as Americans consider the implications of affirmative action, polls reflect that more Americans believe that grades and standardized tests should be top factors in college admissions considerations.

64% of Americans agree that increasing diversity within universities and colleges is positive.

IMPACT

So what does affirmative action statistically look like in practice? A Stanford University sociologist estimates that roughly 100 top-tier universities are thought to practice race-conscious admissions practices. Within that pool, roughly 10,000-15,000 degrees are conferred for Black and Hispanic students each year that might not have been accepted otherwise. That represents about 1 percent of all students in four-year colleges, and about 2 percent of all Black, Hispanic or Native American students in four-year colleges. Since the 1960s, medical schools across the country saw a jump in the number of Black Americans in medical programs by a factor of four, according to a 2000 study by economists from Georgetown University and Michigan University.

States Banning Affirmative Action

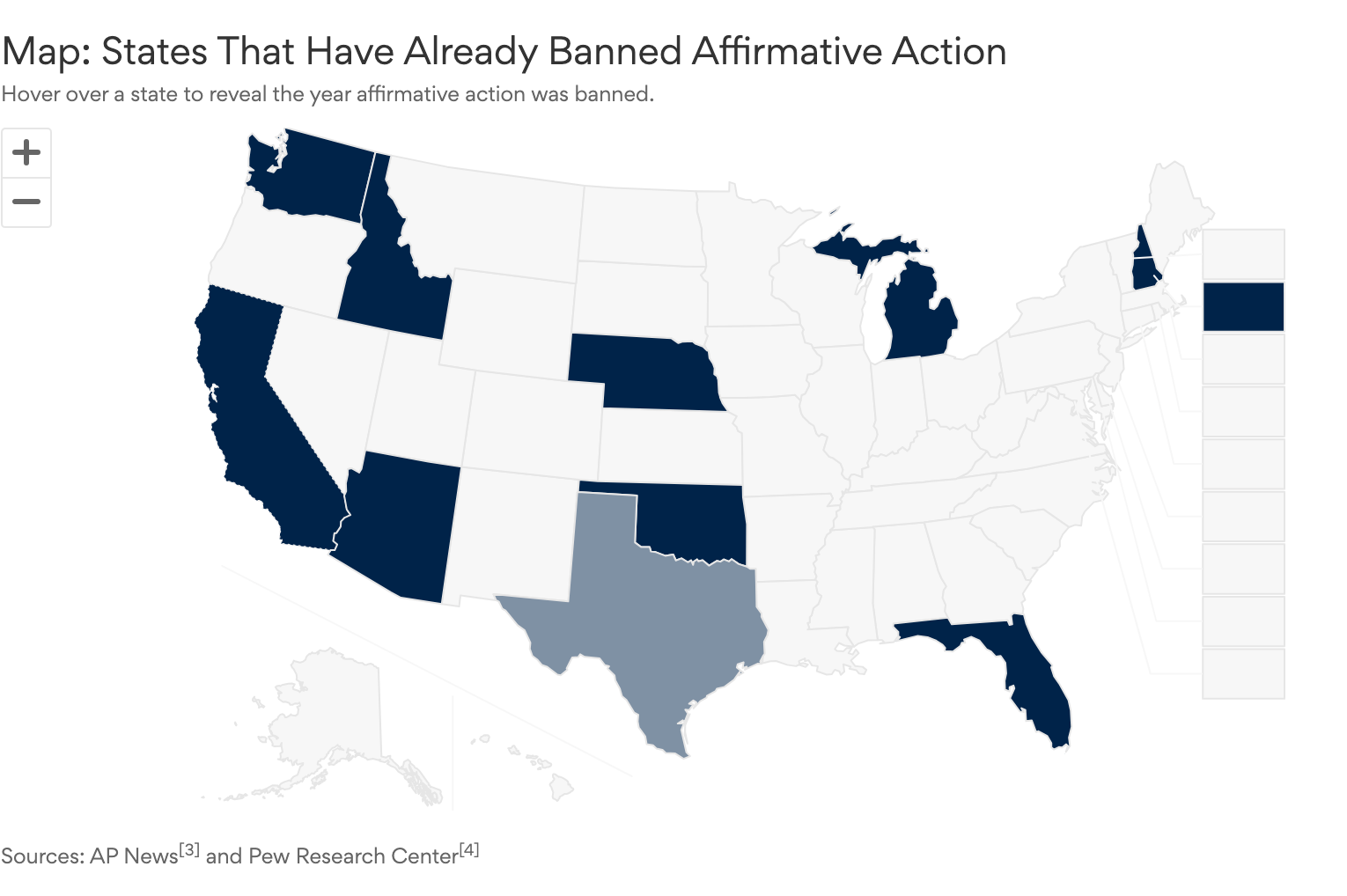

Ahead of the June 2023 Supreme Court ruling, nine states had already banned affirmative action, with one state (Texas) reversing the banned measures and another (Colorado) failing to pass the measures.

While affirmative action policies and processes in higher education consider race as a factor for admission, the processes typically do not consider Asian students to be underrepresented minorities in any application factors. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 64% of Asians ages 18-24 years old were enrolled in higher education programs in 2020, while 41% of white 18-24-year-olds, 36% of Black and Hispanic 18-24-year-olds and 22% of American Indians and Alaskan Natives of the same age were enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the total undergraduate population in the United States is made up of 56% Whites, 19% Hispanics, 14% Blacks, 6% Asians, and 1% Native Americans. Some studies show that these numbers have varied in recent years, but they overwhelmingly represent the same proportions.

As a reminder, the proportions of Black, Hispanic, and Asian people in the US population, according to the 2020 Census, are:

- Black or African American: 13.4%

- Hispanic or Latino: 18.5%

- Asian: 6.1%

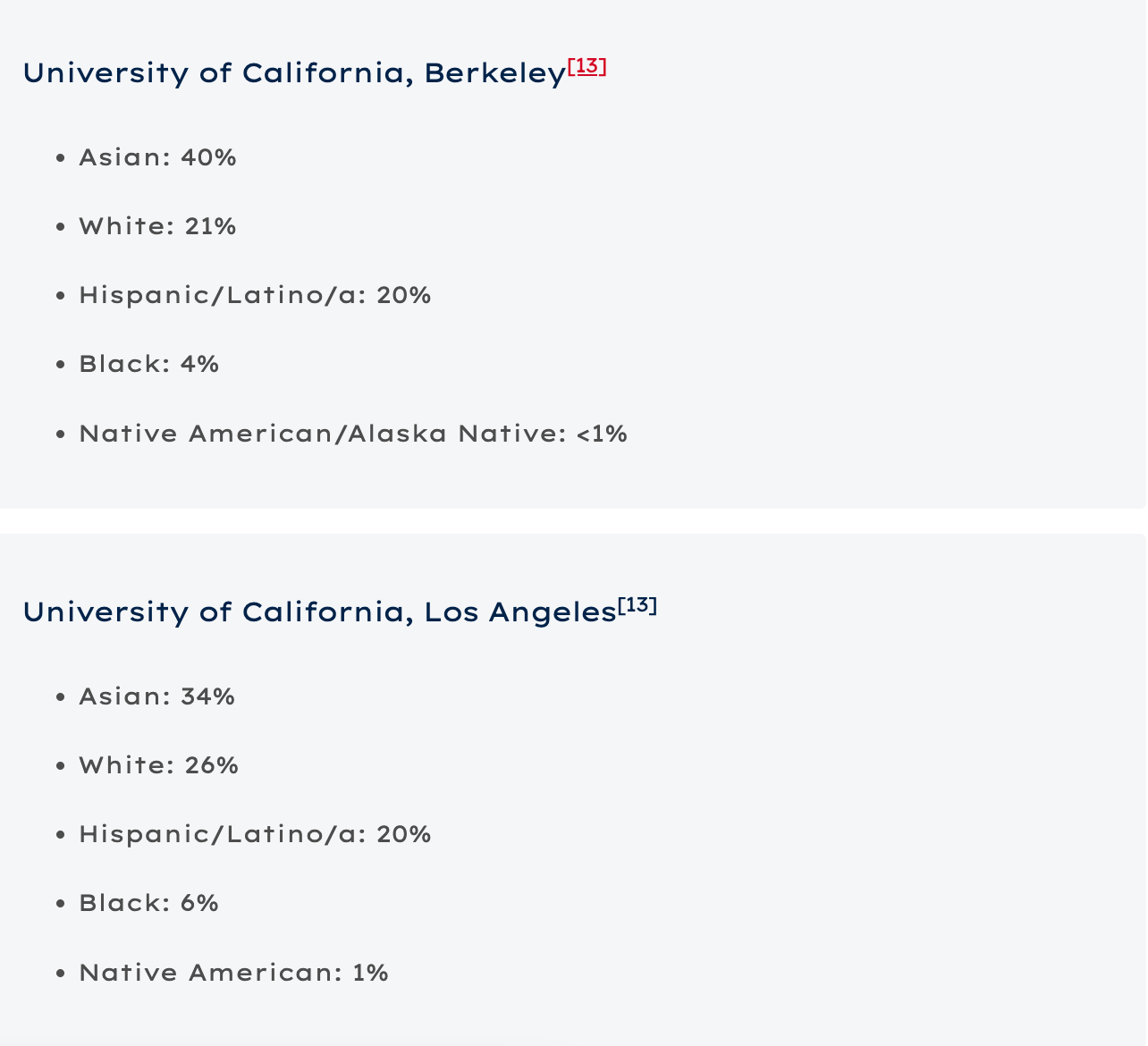

California was first to ban affirmative action

California was the first state to ban affirmative action in public universities in 1996. Below is California’s demographic breakdown of the two most competitive public colleges:

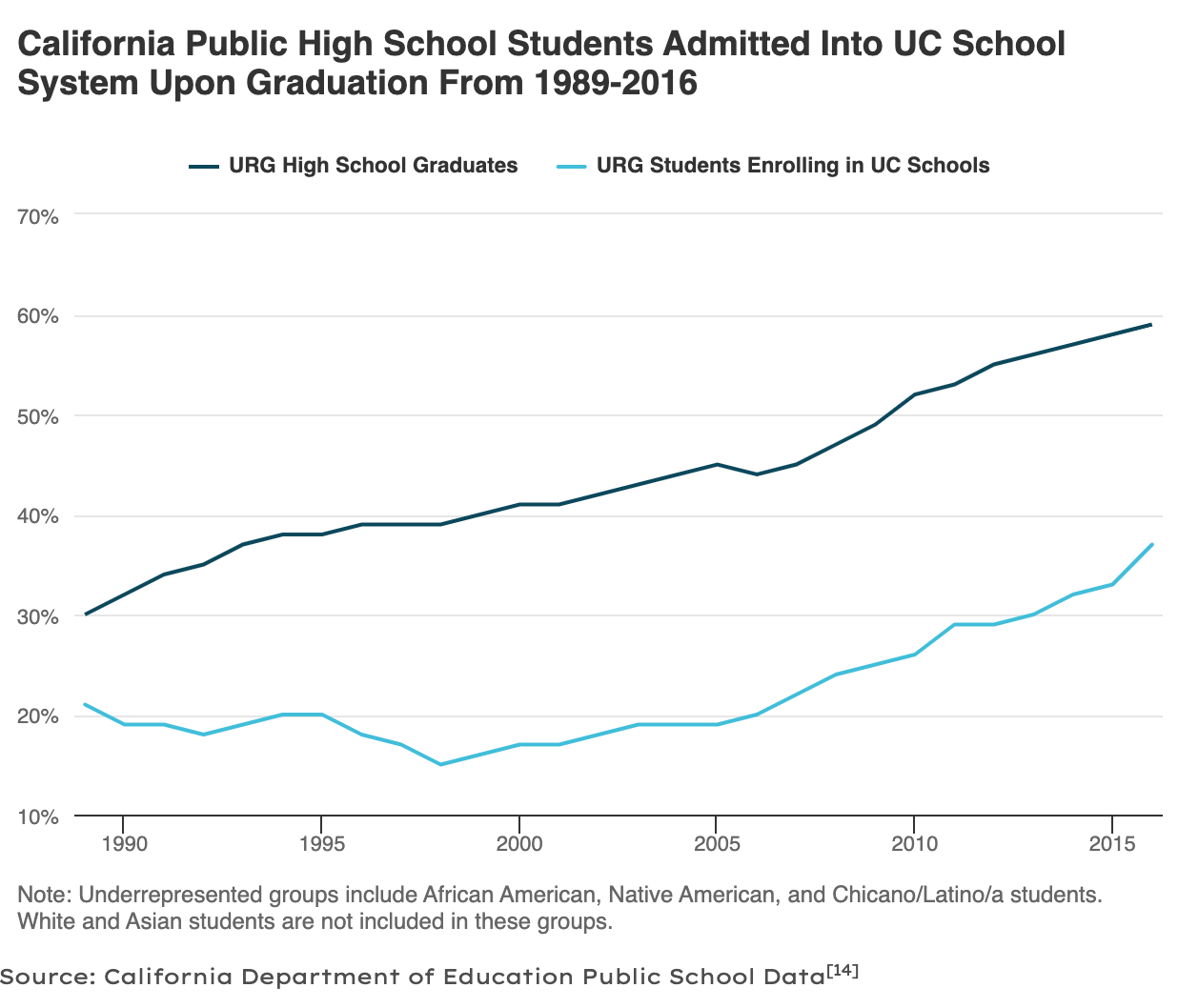

While the number of students from underrepresented groups (URGs) initially dipped following the ruling banning affirmative action, the numbers began to pick back up in 2006.

As of 2022, California utilizes a guaranteed admission system for all in-state high school graduates within the top 9% of their class and has shown a steady increase in under-represented community admissions.

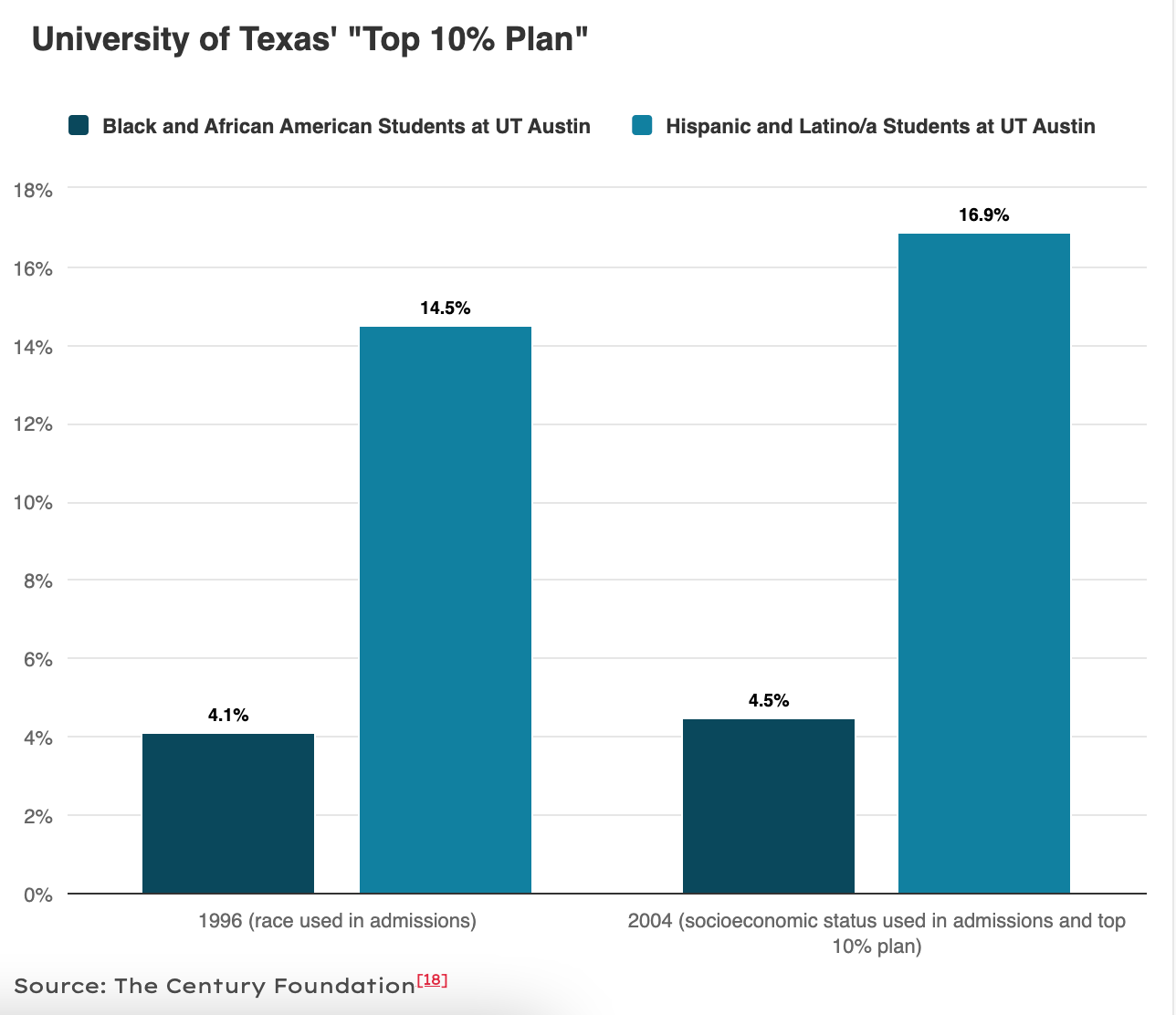

Texas using socioeconomic status

Texas reversed the 1996 affirmative action ban in 2003 but has implemented a mixed approach adding in additional factors of socioeconomic background alongside high school performance. The University of Texas currently honors in-state high school graduates in the top 6% of their graduating class with admission. As seen in the chart below, the percentage of students admitted using factors of race and students admitted using factors of socioeconomic status are nearly identical.

Among schools that practice affirmative action, race and ethnicity often serve as a tiebreaker when admissions officers have difficulty choosing from a pool of strong candidates.

Standardized Testing

“Test optional” policies grew rapidly throughout the pandemic, and many predict this will become the new normal in college admissions processes. Around 1,900 colleges and universities have already dropped test requirements. The number of students taking the SAT dropped from 2.2 million in 2020 to 1.7 million in 2022.

- A 2015 study by the College Board found that students from families with incomes below $25,000 scored an average of 168 points lower on the SAT than students from families with incomes above $100,000.

- A 2017 study by the National Center for Education Statistics found that the average ACT score for students from low-income families was 18.6, while the average ACT score for students from high-income families was 24.1.

- A 2018 study by the Pew Research Center found that the gap in SAT scores between white and Black students has remained relatively unchanged since 1972.

Black students score lower than White students on vocabulary, reading, and math tests, as well as on tests that claim to measure scholastic aptitude and intelligence. The gap appears before children enter kindergarten, and it persists into adulthood. It has narrowed since 1970, but the typical American Black still scores below 75 percent of American Whites on almost every standardized test. According to this commentary from Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips at Brookings, “Closing the black-white test score gap would probably do more to promote racial equality in the United States than any other strategy now under serious discussion.” A study published in the peer-reviewed American Educational Research Journal in April 2021 found that test-optional admissions increased the share of Black, Latino, and Native American students by only one percentage point at about 100 colleges and universities. Likewise, low-income students, as measured by those who qualify for federal Pell Grants, also only increased by only one percentage point, compared to similar schools that continued to require SAT and ACT scores.

Black students score lower than White students on vocabulary, reading, and math tests, as well as on tests that claim to measure scholastic aptitude and intelligence. The gap appears before children enter kindergarten, and it persists into adulthood. It has narrowed since 1970, but the typical American Black still scores below 75 percent of American Whites on almost every standardized test. According to this commentary from Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips at Brookings, “Closing the black-white test score gap would probably do more to promote racial equality in the United States than any other strategy now under serious discussion.” A study published in the peer-reviewed American Educational Research Journal in April 2021 found that test-optional admissions increased the share of Black, Latino, and Native American students by only one percentage point at about 100 colleges and universities. Likewise, low-income students, as measured by those who qualify for federal Pell Grants, also only increased by only one percentage point, compared to similar schools that continued to require SAT and ACT scores.

The Role of Government

FEDERAL

The role of the federal government in affirmative action has played a crucial part in shaping and enforcing policies to promote equal opportunity and combat discrimination.

The federal government’s involvement in affirmative action can be traced back to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VI of the Act prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. In 1965, President Johnson issued Executive Order 11246, which required federal contractors to take affirmative action to eliminate discrimination and establish equal opportunity policies.

Furthermore, the federal government has established various agencies to oversee and enforce affirmative action policies. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) within the Department of Labor ensures that federal contractors and subcontractors comply with affirmative action obligations. The OFCCP conducts audits and reviews to ensure employers are actively working towards achieving equal employment opportunities.

The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is another federal agency involved in affirmative action. The OCR enforces Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and investigates complaints of discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal funding. It plays a vital role in ensuring that schools and colleges promote diversity and equal access to education.

Over the years, affirmative action policies and their implementation have been the subject of debate and legal challenges. The Supreme Court plays a crucial role, and its decisions have provided guidance on the constitutionality and permissible use of affirmative action in federally funded institutions such as universities.

STATE

States have the authority to enact legislation regarding affirmative action within their respective jurisdictions. Here are a few examples of the type of legislation that can be passed:

- Ban, Repeal, or Amendment on Affirmative Action: States can pass laws prohibiting affirmative action in areas such as college admissions, public employment, or government contracts. These laws aim to prevent considering race or other protected characteristics in decision-making processes. Nine States, including California and Texas, have banned affirmative action.

- Preferential Treatment Prohibition: Some states have enacted legislation that explicitly prohibits preferential treatment based on race, gender, or other protected characteristics. These laws aim to ensure equal treatment and prohibit any form of discrimination or preferential treatment in areas like employment, education, or contracting. California (Proposition 209), Washington (Initiative 200), Michigan (Proposal 2), Arizona (Proposition 107), and Nebraska (Measure 424) have passed such measures.

- Diversity Programs or Outreach Initiatives: States can also pass legislation to encourage diversity programs or outreach initiatives without explicitly employing affirmative action policies. These programs aim to promote diversity and equal opportunities without considering race or other protected characteristics as a determining factor. Illinois, NY, Texas, California, and Florida provide support for high-achieving and low-income students.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT: EDUCATION

At the state and local level, school districts can tackle the true underlying issue – that minority students, particularly Black children, are nearly three times as likely to live in poverty than White children, and are concentrated in high-poverty schools. Affirmative action has simply failed to bridge the gap of educational opportunity that starts in kindergarten.

“If we want to improve educational opportunities and learning for students, we want to get them out of these schools of high-concentrated poverty,” said Stanford University Graduate School of Education professor Sean Reardon who evaluated hundreds of millions of standardized test scores to reach his conclusions.

State-level initiatives that increase access to high-quality education for all students include school choice and parental empowerment policies, as well as programs designed to improve teacher quality, reduce classroom size, and leverage technology to improve outcomes – especially for students trapped in low-performing schools.

In 2015, the nation’s report card showed that 18% of 4th-grade Black kids read at or above Proficient. In 2019 only 15% of that cohort, now in 8th grade, was reading at or above Proficient levels. Ian Rowe, a scholar at American Enterprise Institute and Founder of Vertex Partnership Academies, stated, “Now in 2023, it’s very likely that less than 20% of that SAME cohort of black high school seniors is reading at Proficient levels. The biggest issue that group faces is not the lack of affirmative action to get into college. It’s being ill-prepared before even getting there.

“That is the truth we have to confront. Stronger families and more school choice have to be part of the story so that our kids can compete on equal footing, far before college applications are on the table,” Rowe said. To learn more about education reform, review The Policy Circle Briefs on Education Innovation, Education Savings Accounts, and K-12 Education in the United States.

THE PRIVATE SECTOR

The recent SCOTUS rulings will impact not only higher education but hiring processes in the private sector as well. As colleges look to change their admissions practices, corporations and businesses will also examine race-conscious diversity programs, hiring initiatives, and practices following this ruling.

As we stated in the role of The Federal Government section, the federal government prohibits organizations from taking race, sex, religion, or national origin into consideration within the hiring practice through various laws and regulations.

HIRING AND EMPLOYMENT

While affirmative action is typically thought of in relation to the college admissions process, hiring processes and employment-based affirmative action policies are also important to analyze. In a study analyzing Executive Order 11246, an affirmative action policy focused on employment and, more specifically, the targeting of firms holding contracts with the federal government, researchers found the affirmative action policy to be ineffective. Through the analysis conducted by researchers within the Center for Economic Studies (CES), it was determined that the employment-based affirmative action policy had “no effect on employment shares or on hiring for any minority group.”

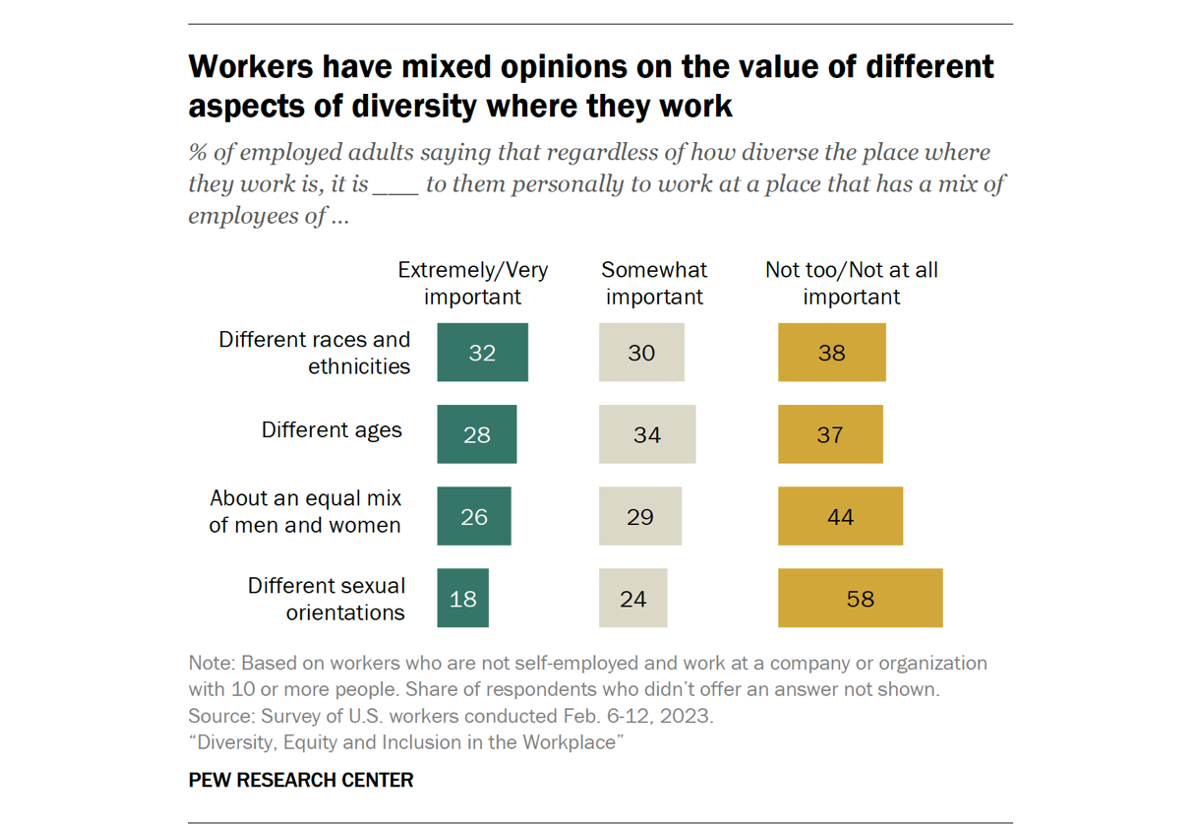

In a Pew Research Survey, 74% of U.S. adults shared that companies and organizations should only take a person’s qualifications into account, “even if it results in less diversity.” About 24% of respondents said that companies should take into account a person’s race and ethnicity to increase levels of diversity.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, addressing racial preferences in college admissions, may have implications for corporations.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, addressing racial preferences in college admissions, may have implications for corporations.

- Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 applies the Equal Protection Clause to private universities receiving federal financial assistance, while Title VII applies similar anti-discrimination principles to private businesses with over 15 employees.

The ruling may prompt closer scrutiny of racial preferences and DEI policies in the corporate world. An opinion piece in the WSJ by Michael Roth, an attorney in Texas, suggests the following considerations:

- Policies should align with equal protection principles and avoid racial balancing or quotas, which may be considered as discrimination.

- Race as a “plus factor” in hiring and promotion may face scrutiny under Title VII.

- Diversity training should not create a hostile work environment, as it can be considered employment discrimination under Title VII.

- Equal opportunity and genuine inclusivity, treating individuals as individuals rather than members of racial, religious, sexual, or national groups, should be the focus of diversity policies.

Companies and organizations have shared direct goals and practices adopted to focus on increased racial representation in recent years. The shifts following the rulings may impact how employers search for recruits and impact other diversity programs. The Supreme Court rulings will impact public institutions under the 14th Amendment, with potential impacts on workplace discrimination through Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which guarantees “equal employment opportunity.”

THE NONPROFIT SECTOR

Similar to private companies and organizations, nonprofit practices may also be impacted by the latest affirmative action rulings. Section 1981 of the Civil Rights Act 1866 has come under analysis in light of the recent ruling in relation to specific programs that may be designed and seeking grants to focus on specific racial minorities.

Section 1981 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in the making and enforcing of contracts. In recent years, there has been a growing debate about whether Section 1981 can be used to challenge affirmative action programs that focus on specific racial minorities.

In 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in CBOCS West, Inc. v. Humphries that Section 1981 prohibits retaliation against individuals who complain of discrimination. This ruling has led some to argue that Section 1981 can also be used to challenge affirmative action programs, as these programs can sometimes lead to the denial of contracts to white or Asian applicants.

However, other legal scholars have argued that Section 1981 does not apply to affirmative action programs. They argue that Section 1981 is intended to protect individuals from discrimination, not to challenge government policies that are designed to promote equality.

Race-Based Consideration

While opinions on affirmative action’s effectiveness and ethical implications vary, proponents argue that there are potential benefits to consider.

- Promoting diversity and inclusion: Affirmative action can help foster a more diverse and inclusive workforce or educational environment. It aims to provide representation for historically underrepresented groups, giving them access to opportunities that were previously limited due to systemic biases and discrimination. By including individuals from diverse backgrounds, organizations, and educational institutions can benefit from a range of perspectives, experiences, and talents, which can lead to increased innovation and creativity.

- Addressing historical discrimination: Affirmative action is intended to rectify the effects of past discrimination and promote social justice. It acknowledges the barriers faced by marginalized groups due to historical inequalities and aims to provide them with a fairer chance at education and employment opportunities. By considering race as one factor among others, affirmative action attempts to level the playing field and create more equitable outcomes.

- Enhancing representation and role models: Affirmative action can lead to increased representation of underrepresented groups in positions of influence and authority. This can serve as a source of inspiration and empowerment for individuals within those groups, providing them with visible role models and the knowledge that their own aspirations are achievable. It also challenges stereotypes and contributes to breaking down barriers for future generations.

- Creating educational and economic benefits: Studies have suggested that diversity in educational settings and workplaces can yield positive outcomes. Exposure to diverse perspectives and experiences can enhance critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and cultural competence. Additionally, promoting diversity can contribute to economic growth and competitiveness by tapping into a wider talent pool and fostering creativity and innovation.

Race-based selection can be seen as problematic for several reasons.

- Equality and fairness:Race-based selection can be perceived as unfair and inconsistent with the principle of equal opportunity. It treats individuals differently based on race or ethnicity, potentially disregarding merit, qualifications, and abilities. Critics argue that individuals should be judged on their qualifications and achievements rather than their race.

- Stigmatization and stereotyping:Race-based selection can perpetuate stereotypes and reinforce the idea that individuals from certain racial or ethnic backgrounds possess specific traits or abilities. This can lead to stigmatization and undermine efforts to treat people as individuals, potentially reinforcing biases and divisions based on race.

- Reverse discrimination:Critics argue that race-based selection can result in reverse discrimination, where individuals from historically privileged groups may face disadvantages solely based on their race or ethnicity. This may create resentment and undermine social cohesion.

- Inaccurate representation:Supporters of colorblind policies argue that race-based selection may not necessarily lead to an accurate representation of diversity. It assumes that individuals from the same racial or ethnic background share similar experiences, perspectives, and needs, which can oversimplify the complexities of identity and diversity.

- Legal and ethical challenges:Race-based selection may face legal challenges if it violates anti-discrimination laws or equal protection principles, as there is strict scrutiny for racial classifications. Affirmative action policies, for example, have faced legal scrutiny in various jurisdictions, with courts imposing limitations on the extent to which race can be considered in decision-making.

It is important to note that opinions on race-based selection vary, and perspectives differ on addressing historical inequities and effectively promoting diversity. Public debate and legal considerations significantly shape policies related to race-based selection in different contexts.

A Path Forward

Race-based considerations will be in flux for the foreseeable future. For now, as it relates to admissions, universities can adopt various approaches that have shown promise in promoting diverse student populations, including opportunities to foster opportunities for low-income students’ access, boosting financial aid, and developing recruitment and support systems for low-income students.

Other approaches can help promote more opportunities for minority students, for example:

- Early Outreach Programs: Universities can establish outreach programs that target underrepresented communities, including high schools and community colleges. These programs can provide information about college opportunities, offer mentoring and guidance, and assist students in navigating the admissions process, but also they can hold high schools accountable for the college readiness of their students.

- Financial aid and scholarships: Universities can provide financial aid packages and scholarships specifically aimed at supporting students from low-income families in specific geographies. These initiatives can help alleviate financial barriers and make higher education more accessible.

- Partnerships with community organizations: Collaborating with community organizations and nonprofits that work with underrepresented groups can help universities reach and engage with potential students. These partnerships can involve joint programs, mentorship initiatives, and college readiness workshops.

- Holistic admissions process: Adopting a holistic admissions process allows universities to consider a wide range of factors beyond test scores and grades. This approach enables admissions officers to evaluate applicants’ experiences, backgrounds, and personal qualities, giving them a more comprehensive understanding of each candidate’s potential.

- Targeted recruitment efforts: Universities can actively recruit students from underrepresented groups by attending college fairs, hosting informational sessions, and visiting schools with a higher concentration of these students. Building relationships with guidance counselors and community leaders can also help reach and attract prospective students to apply and be ready to succeed.

- Mentorship and support programs: Implementing mentorship programs where current students or alumni provide guidance and support to underrepresented students can be beneficial. Additionally, providing academic support services, counseling, and resources tailored to the needs of underrepresented students can contribute to their success and overall well-being.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s rulings on affirmative action have undoubtedly shaped the landscape of education and employment policies in the United States. Over the years, the Court has grappled with complex questions surrounding race-conscious admissions and hiring practices, striving to strike a balance between promoting diversity and ensuring equal protection under the law. While the Court’s decisions have elicited both praise and criticism from various corners of society, it is clear that affirmative action must be re-examined and its initial goals revisited. Now, we have an opportunity to address the underlying issues and find solutions that ensure better outcomes for all students – especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds and underserved areas. Now the focus needs to be on the end goal, which is for underrepresented groups to be ready to seize all opportunities to better their lives.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

- Measure: Are you familiar with the admission process of colleges and universities within your state or county? Do you know your state’s history with affirmative action? Were colleges in your state already banned from using race and ethnicity in applications, or will the verdict of the Supreme Court alter the admissions process?

- Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community?

- Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected or appointed officials taken in response to the Supreme Court ruling on affirmative action?

- Discover how colleges, universities, and employers adjust their policies to offer diversity and equal opportunity.

- Reach Out: Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state. Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards and related organizations such as PTAs, your local chamber of commerce or local businesses.

- Plan: Set milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar or local community calendar.

- Execute: As the Supreme Court will play a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of future affirmative action policies, stay updated on any rulings or cases brought to the Court associated with racial classifications, college admissions, or equal opportunity.

- Look into education governance and the committees that set goals and visions, such your state’s Higher Education Board or local institutions’ boards of trustees.

- Establish a relationship with your legislators. It’s easy to establish a relationship with your legislators. Start by introducing yourself. You can also learn to write to your representatives or set up a meeting with a legislator on The Policy Circle website.

Consider writing a letter to the editor or an op-ed on your stance on new innovative practices in education in your local paper. Learn how on The Policy Circle website.

Newest Policy Circle Briefs

The First-Time Voter Guide

Assessing Candidate Guide

Women and Economic Freedom

About the policy Circle

The Policy Circle is a nonpartisan, national 501(c)(3) that informs, equips, and connects women to be more impactful citizens.