Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this Brief.

An Experiment Unique in the World

Upon signing the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin famously said, “We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” To the colonists, the Declaration of Independence justified rebellion, but they were aware their actions were treasonous in the eyes of Great Britain. Even when independence had been assured, Franklin and the other founders knew their challenges had not ended. After the Constitutional Convention was adjourned and a citizen asked Franklin what kind of government had been structured, Franklin is said to have answered: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

It is important to remember this was the great American experiment. Our leaders at the time constantly feared one wrong decision could put an end to this experiment of an empowered, free people. Such an undertaking was unprecedented, and its success was improbable. Franklin’s retorts “suggested the survival of freedom depends on the people, not parchment.”

Over two-hundred years later, this fact is something Lin-Manuel Miranda and Heidi Schreck wanted to explore in their Broadway plays. Miranda’s Hamilton, about the “young rebels grabbing and shaping the future of an unformed country,” brings to life “history itself, that collision of time and character that molds the fates of nations and their inhabitants.” In Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me, she presents the Constitution not as “a staid document gathering mold on a shelf somewhere” but as “a force that fundamentally reaches into our lives, shaping everything from our understanding of ourselves to our interpersonal relationships.”

As debates carry on about citizenship, immigration, the Census, representation, redistricting, equal protections, individual rights, and the roles of states and the federal government, the fact that plays about the Founding Fathers and the U.S. Constitution have garnered attention, nominations, and awards illustrates the continued importance and relevance of America’s history and most important document. Perhaps the most important question is: What does the Constitution mean to you?

Why it Matters

Since the Founding Fathers replaced the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution and subsequent Bill of Rights, the relationship between federal power and state authority has been thoroughly debated. A healthy tension arose in the debates between those in favor of states’ rights (like Thomas Jefferson) and proponents of a strong central government (like Alexander Hamilton). That tension defines the ongoing debates outlined below.

So really, why do we care? If we do not understand the document that grants us our unique freedoms, we will not have a full understanding of the impact these freedoms have on our lives. Most students in the U.S. study the Constitution in middle school, but revisiting the document as an adult can highlight real avenues for informed and active civic participation to ensure we keep that ability for our generation and those to come.

Putting it in Context

History: The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights

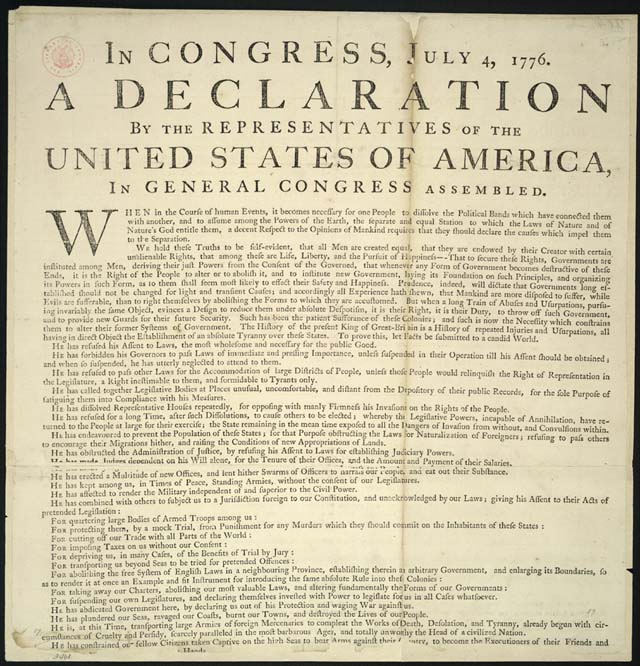

In 1774, a group of delegates met in Philadelphia in the First Continental Congress to voice their grievances through a petition to King George III. When the Second Continental Congress met in 1775, the American Revolution was already underway. Congress formed the Continental Army, “effectively took over as the de facto national government,” and on July 4, 1776, officially adopted the Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson.

While still at war in 1777, the Continental Congress adopted the nation’s first constitution, titled the Articles of Confederation, “to avoid a powerful federal government with the ability to invade rights and threaten private property.” The Articles of Confederation, however, were too weak to bring together “a fledgling nation that needed both to wage war and to manage the economy.”

While still at war in 1777, the Continental Congress adopted the nation’s first constitution, titled the Articles of Confederation, “to avoid a powerful federal government with the ability to invade rights and threaten private property.” The Articles of Confederation, however, were too weak to bring together “a fledgling nation that needed both to wage war and to manage the economy.”

In 1787, the founders met again in Philadelphia and produced the Constitution that focused on creating a capable central government. During the ratification process, “many states proposed amendments specifying the rights that Jefferson had recognized in the Declaration.” In 1791 these amendments officially became the Bill of Rights.

The Declaration of Independence “made certain promises about which liberties were fundamental and inherent, but those liberties didn’t become legally enforceable until they were enumerated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.” Specifically, the Constitution created a strong central government to preserve liberty, and the Bill of Rights set limitations on that government.

The Declaration of Independence “made certain promises about which liberties were fundamental and inherent, but those liberties didn’t become legally enforceable until they were enumerated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.” Specifically, the Constitution created a strong central government to preserve liberty, and the Bill of Rights set limitations on that government.

To further explore ratification, the federalist papers, the Constitutional Convention, and the Bill of Rights, see the interactive documents from the Ashbrook Center’s Teaching American History.

The Big Debate

Striking a balance between a central government that was capable of sustaining itself but was not as powerful as Britain sparked a tension between founders, particularly Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. The Constitutional Convention pitted Federalists like Hamilton and Adams against Anti-Federalists like Jefferson and Madison. Federalists believed states were preventing the nation as a whole from becoming a rising economic power by impeding commerce with tariffs, while Anti-Federalists believed the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government and too little power to the states, which could better reflect more localized interests.

This healthy tension is key to debates that rage on in Congress, and our understanding of the well-intended motivations (on both sides) is critical for keeping our democracy strong. The Federalist Society explores this debate more.

The Role of Government

By the People, For the People

The authors of the Constitution believed “the only legitimate form of government was one in which public authority derived entirely from the people,” but this did not make it any easier to decide how “to implement principles of popular majority rule while at the same time preserving stable governments that protect the rights and liberties of all citizens.”

Many believe that, to be called a democracy, a country’s government must engage in a direct democracy, “in which the people of a state or region vote directly for policies.” In a republic, “supreme power resides in a body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by elected officers and representatives.” Hamilton referred to this as a ‘representative democracy,’ capturing the democratic nature of a government by the people, but the representative nature of a republic that did not allow a rule of the majority to dictate the will of the minority.

Many believe that, to be called a democracy, a country’s government must engage in a direct democracy, “in which the people of a state or region vote directly for policies.” In a republic, “supreme power resides in a body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by elected officers and representatives.” Hamilton referred to this as a ‘representative democracy,’ capturing the democratic nature of a government by the people, but the representative nature of a republic that did not allow a rule of the majority to dictate the will of the minority.

The U.S. Constitution: An Overview

At 4,400 words on four pages, the U.S. Constitution is the oldest and shortest written constitution of any government in the world. As the U.S.’s “written charter of government,” the Constitution affirms “the government of the United States exists to serve its citizens” and specifies the “supremacy of the people through their elected representatives.”

The Constitution begins with the Preamble, the introduction that clarifies the purpose of the document and the power of the people, emphasized by the first words: “We the People.” After the Preamble, the Constitution is divided into seven articles:

- Articles I, II, and III outline and assign specific responsibilities to the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government, respectively.

- Article IV transitions from the federal level to the state level, and addresses the relationship between the states.

- Articles V is more procedural, detailing how to amend the Constitution.

- The final two articles give the Constitution its power: Article VI declares the Constitution to be “the supreme Law of the Land” and Article VII ratifies the Constitution.

After the seven articles come the first ten amendments, which constitute the Bill of Rights, followed by the rest of the 27 amendments. To learn more about when the U.S. Constitution has been amended, visit Kite & Key Media’s video here.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

The Electoral College

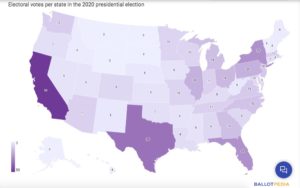

Article II, Section 1, Clauses 2 and 3 of the Constitution specifies that the President be elected by the Electoral College, a group of 538 Electors appointed by the states and the District of Columbia. The Electoral College is a Constitutional institution meant to govern the process of selecting the President and Vice President. Each state has a specific number of Electors, as is set forth in the Constitution.

The power of states to award Electoral votes was solidified in McPherson v Blacker in 1892, when the Court maintained “the appointment and mode of appointment of electors belong exclusively to the states under the Constitution of the United States.” Currently, 48 states appoint Electors on a “winner takes all” basis, meaning all the electors go to the candidate that wins in the state. Maine and Nebraska award Electors based on Congressional District winners, and the remaining two electoral (which come from the numbers for 2 senators) go to the statewide winner.

The Electoral College has on occasion produced controversial elections, the first of which can be dated back to 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, both on the Democratic-Republican ticket, received the same number of electoral votes. The Electoral College has gained a lot of attention in recent decades; in 2000, Al Gore won the popular vote by .5% but George W. Bush won the Electoral College by 5 votes. Again in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by 2.1% while Donald Trump won the Electoral College by 77 votes.

The National Popular Vote Movement

Given that the Constitution gives states control over how to award their electoral votes, there have been proposals to change the Electoral College system. In 2007, a movement for a National Popular Vote (NPV) gained traction in Maryland. According to the plan, the NPV would be “an interstate agreement for states to appoint their Electors for the winner of the national popular vote rather than the winner in each state.” As of mid-2021, 15 states (Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, Vermont, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, California, Illinois, New York) and the District of Columbia, with a total of 195 electoral votes, have passed the bill into law. For now, this measure will not affect elections in those states; as it is written, the National Popular Vote bill will only go into effect when it is enacted into law by states possessing 270 electoral votes.

The Debate

Supporters of the Electoral College assert it preserves “an important dimension of state-based federalism in our presidential elections” and guarantees “our President will have nationwide support.” A national popular vote would give the most populous states the majority of the electoral power; candidates would spend time in heavily populated cities, and give little attention to smaller, rural areas.

Critics of the Electoral College argue that it negatively affects most states by reducing “the real field of play to fewer that a dozen ‘swing states,’” which “dramatically polarizes the nation’s politics while reducing voter turnout.” Many critics of the Electoral College are in favor of the NPV plan, claiming it would guarantee the Electoral College winner is the popular vote winner and that “every part of the Union would attract political investment and campaigning” rather than only a few key states.

For more on the debate surrounding the Electoral College, see The Policy Circle’s Electoral College Deep Dive.

Current States’ Rights Issues

Immigration

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “establish a uniform rule of naturalization.” Some have made the case that “naturalization” refers to citizenship and that this clause does not give the federal government the power to restrict immigration. Others maintain Congress’s designation to “declare war, provide for the common defense, and define and punish offenses against international law,” bring immigration laws into the federal domain. In general, in the past decades, “the federal government decides who’s allowed in, while states provide services for them once they are here.”

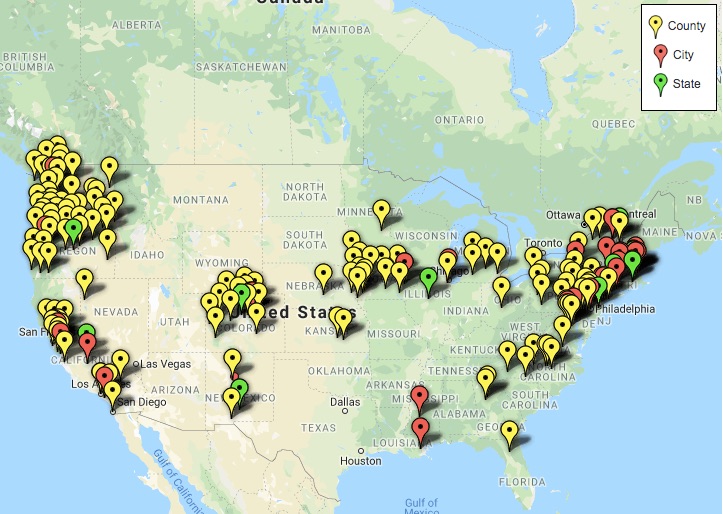

States have taken on a much bigger role in immigration particularly since 1996, when the federal government began training local law enforcement agencies to arrest and screen suspected unauthorized immigrants. The federal government also grants states authority over distributing drivers’ licenses and occupational licenses related to employment for noncitizens, and over budget and appropriation laws pertaining to public programs for immigration integration as well as English language and citizenship classes.

In 2019, lawmakers in 45 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico enacted 181 laws and 135 resolutions related to immigration. Bills addressed census counts, sanctuary laws, drivers’ licenses, funding, and state law enforcement. In 2020, lawmakers in 32 states and Washington, D.C. enacted 127 laws and 79 resolutions related to immigration, a notable decrease since many legislatures were focused on the coronavirus pandemic and economic crises.

Authority is still disputed in some cases. For example, in August 2019, North Carolina’s governor vetoed a bill that would have required law enforcement officers to comply with ICE requests to hold illegal immigrants subject to deportation, saying it “weakens law enforcement in North Carolina by mandating sheriffs to do the job of federal agents.” Two months prior in June, Florida’s governor signed into law a similar measure that would have required local law enforcement agencies to cooperate with federal immigration authorities.

Immigration programs have frequently caused debate as to whether the programs violate the separation of powers. For example, there are a number of challenges against the legality of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the creation of Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA), based on whether or not the president overstepped executive authority to create these programs. For more, see The Policy Circle’s Immigration Brief.

Healthcare

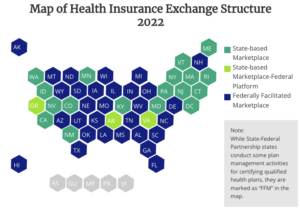

Particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, health care is a preeminent issue. States are the primary regulators of private insurance, but federal laws such as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and programs such as Medicaid and Medicare do not leave states with all the power. Idaho’s Blue Cross insurer, for example, tried to implement a plan that would help the state financially but would charge higher premiums for sick people or people with preexisting conditions. Federal officials struck the plan down, as it violated ACA regulations.

Some states also assume greater responsibility than others. Over half of all states have decided to let the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) run their exchanges on the ACA marketplaces. In Texas, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, HHS reviews insurance rates, whereas states including New York have their own department that reviews insurance. There is a level of collaborative flexibility between states and the federal government. Take Medicaid, which is administered jointly at the federal and state levels, as an example. States can obtain section 1115 waivers, which “allow states to sidestep certain requirements to reform their Medicaid programs to better suit their unique needs.”

The highly controversial idea of Medicare for All, or a single-payer healthcare system, under which the federal government provides Americans with universal health insurance, has gained momentum in public discourse. This would heavily affect states since states currently exert control over private health insurance, such as through provider and insurer regulations. States also control physician licensing and run state employee health plans. However, some states are also pushing forward the idea of single payer systems; Michigan, Minnesota, and New York have all introduced legislation moving towards single-payer health care systems. See The Policy Circle’s Healthcare Brief for more.

Education

Prior to the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, the federal government did not interfere very much with local education policy. Many states objected to federal reach via the Act’s accountability demands, particularly because some studies noted “that strict accountability regulations based solely on test scores did little to improve student achievement.” In December 2015, Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which replaced and updated the No Child Left Behind Act and “moved the federal accountability aspects to the States.” The ESSA makes states submit their plans to the U.S. Department of Education for approval, but still allows them “flexibility to chart their own path to educational success.”

Academic standards have proven to be one area debated under state and federal authority. The academic standards known as Common Core, a controversial set of learning standards to be used across states, was an effort coordinated by the Council of Chief State School Officers and the National Governors Association. An outside group of specialists that did not include any licensed educators drafted the standards, although teachers participated in the review process. The standards were based on the idea that “the nation’s 40 million K–12 students should be offered the same high-standard education no matter where they go to school.”

In 2011, the federal government tied portions of funding for the (also controversial) Race to the Top educational grant program to Common Core in an effort to incentivize states to adopt the standards. Even with the more recent ESSA in place, which specifies states have the right to revise or withdraw from Common Core standards and that adopting standards cannot be a condition for receiving other types of federal funding, most states have implemented few changes to their standards.

Besides standards, the pandemic’s toll on students has been “‘the biggest blow to the public education system in decades,'” says Michelle Exstrom, director of the National Conference of State Legislature’s Education Program. Pressures to lower tuition in the private sector, stagnant state funding in the public sector, and lower graduation rates were already weighing on school systems before the pandemic added additional costs and shortcomings in virtual learning.

Federal contributions make up about 8-10 percent of total national spending on elementary and secondary education budgets. This includes funds from the Department of Education, the Department of Agriculture’s School Lunch program, and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Head Start program. For more, see The Policy Circle’s Education: K-12 Brief.

Gun Control

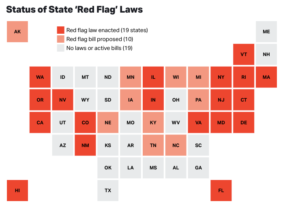

In 1968, the Gun Control Act “gave the federal government an entry point into firearms commerce.” It also paved the way for future interventions, such as the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993, which mandated local law enforcement officials perform background checks on potential handgun purchasers before they could receive a purchased handgun. However, Chief Justice Scalia sided with state power when he ruled that the required background checks were unconstitutional, as they gave the federal government the power to “coercively enlist states in enforcing federal law,” and the law was struck down.

The 1994 case United States v Lopez also played a role in shaping federal authority over gun control on account of the Commerce Clause, which gives Congress authority over interstate commerce. In many cases, Congress can “regulate firearms activity occurring wholly within a state when that activity has, in the aggregate, ‘substantial economic effect’ on interstate commerce.” However, the Court also noted that any “general federal interest in reducing localized gun violence does not have sufficient commercial nexus to satisfy Commerce Clause requirements.”

In 2008 in District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court upheld the Second Amendment, affirming a citizen’s right to bear arms. This also left the federal and state governments in conflict as to how to manage, and who should manage, the potential for restrictions on the Second Amendment, including background checks and concealed carry permits. The Federalist Society takes a closer look at these issues in relation to the Second Amendment. Still, federal leadership plays an important role. Gun control advocates note that anyone can simply drive to a different state to find more lenient gun control laws, and say that national legislation is essential in supporting cooperation across levels of government in terms of enforcement, prosecution, and research and reporting on crime including gun trafficking and illegal firearm possession. Second amendment supporters say expanded background checks can easily go too far.

Another gun rights case is before the Supreme Court, focusing on “whether restrictions on the right to carry a firearms in public for self-defense pass constitutional muster”. At least 20 states “have throughout history prohibited the carrying of all handguns in populous areas or limited public carry to those with ‘good cause’ to carry a concealed firearm.” Based on a century-old law, New York state denied applications for concealed-carry licenses, and the question of whether this violates Second Amendment rights will be decided in Summer 2022.

Today, most gun control advocates acknowledge they have better chances of pushing through legislation at the state level, and for the most part, state gun control laws are more restrictive than federal laws. After the shooting in Parkland, for example, Florida quickly passed a bipartisan bill that increased the minimum age to purchase a rifle to 21. Additionally, 17 states have passed Red Flag Laws, state laws that authorize police to temporarily confiscate firearms from individuals deemed by a court judge to be dangerous to themselves or others. At both the state and national level, gun rights advocates oppose red flag laws in particular, as they allow police to confiscate guns from individuals without granting them due process to defend themselves. The National Rifle Association and the Giffords Law Center both outline state gun legislation.

Federal law only requires licensed dealers to perform background checks, handled by the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). This does not include private sales made at gun shows or online. In February 2019, the House passed legislation, mainly along party lines, that would increase the background checks before individuals can purchase a weapon. The bill did not pass the Senate. The most recent legislation, as of 2022, has cracked down on ghost guns, firearms that are “manufactured in parts and assembled at home,” meaning they have no serial numbers and are untraceable. The Biden administration issued a new regulation requiring manufacturers to add serial numbers to certain parts. Ten states have already established their own ghost gun restrictions.

Conclusion

Looking back to the relationship between Jefferson and Adams – close friends who worked together to write the Declaration of Independence despite having opposing political perspectives – they respected each other and spent years (near and far) corresponding about their beliefs.

Jefferson was most likely never going to support a strong central government, nor was Adams going to believe that power was best delegated to all the individual states. Yet, they learned from each other’s perspectives by defending and explaining their stances, while still taking time to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the counter position.

The backbone of our nation rests on those debates, and requires an active populace to carry the torch. When the American people “grant their adversary moral respect,” they can “understand well…read deeply, listen carefully, watch closely” and focus on working relationships.

The dynamic, interconnected American political system often raises questions as to where authority lies, and can even result in conflicts that make it all the way to the Supreme Court. At the same time, this integrated system allows citizens to voice their concerns and engage at the national, state, and local levels.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

- Ballotpedia provides information on federal, state, and local politics, including officials and their offices, elections and candidates, and political issues and public policy.

- The National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL) provides state legislatures, lawmakers, and staff with resources, support, and connections to help them craft policy solutions and make their voices heard in the national arena.

- The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is “America’s largest nonpartisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators dedicated to the principles of limited government, free markets and federalism.”

- State Policy Network connects and supports state leaders and think tanks, with the goal of advancing and promoting state-based solutions that can yield a national impact.

- The National Governors Association brings together governors from the 55 states, territories, and commonwealths to identify priority issues and find public policy solutions at the local, state, and national levels.

- The Bill of Rights Institute and the National Constitution Center have plenty of informative resources on the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the Founding Fathers. Read the interactive Constitution periodically to refresh your understanding of this important document.

- The Federalist Society tracks upcoming Supreme Court Cases

- Constituting America and the Constitution Center provide educational programming on the Constitution to teach students and adults about the principles of self-governance.

What You Can Do/Ways to Get Involved

Measure: Find out how your state and district are approaching Constitutional separation of state and federal powers.

- Do you know the state of states’ rights is in your community or state?

- Is there any legislation pending in your area of interest, such is immigration or healthcare? Search these areas on Ballotpedia or NCSL for recent information and legislation.

- Are there any court cases pending in your state related to states’ rights?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed official taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Read the interactive Constitution periodically to refresh your understanding of this important document.

- Investigate how the Constitution is taught in schools in your district, or if there are community programs or local organizations that teach young Americans about government and civic responsibility.

- Track bills in the House and Senate, especially ones supported by your elected officials, with GovTrack.

- Track upcoming Supreme Court Cases with The Federalist Society.

- Follow an issue that is important to you and relates to the power of the states.

- Consult with your professional association on their legislative engagement.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on The U.S. Constitution? Consider exploring the following: