Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

The United States has long been referred to as the “indispensable nation” or the “world’s policeman.” Since World War II, America has promoted democracy and prosperity, and opposed dictatorships and human rights abuses, across the globe through its economic, diplomatic, and military engagement. The U.S. has served as a champion of universal freedom and human rights, a pillar of international security and order, and a deterrent to the aggression of rogue regimes.

Yet in the post-Cold War era, the question of what role the U.S. should play on the world stage, and the extent to which the U.S. can serve as “the world’s policeman,” continues to be debated, and has become a central component in conversations surrounding military spending and foreign policy. Decreases in spending during the Obama administration (“leading from behind”) and the “America First” policy of the Trump administration represent shifts in foreign policy.

In his 2014 book America in Retreat: The New Isolationism and the Coming Global Disorder, Pulitzer-prize winning columnist Bret Stephens cautioned about some of the potentially dire consequences brought on by this foreign policy doctrine of isolationism.

Why it Matters

Foreign Policy is defined as the “general objectives that guide the activities and relationships of one state in its interactions with other states. The development of foreign policy is influenced by domestic considerations, the policies or behaviour of other states, or plans to advance specific geopolitical designs… Diplomacy is the tool of foreign policy, and war, alliances, and international trade may all be manifestations of it.”

In recent years, turmoil has rocked the Middle East in the form of increased violence and volatility in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings and the proliferation of Islamist-extremist terrorist groups with radical anti-Western ideologies. The U.S. has long maintained a presence in the region, and as a whole, the Middle East receives more than 50% of total U.S. military aid globally. And yet the region appears to be more unstable now than ever, with a wide range of conflicts and crises.

Putting it in Context

History and U.S. Involvement

U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East was relatively limited until the mid-1900s; prior to this time, European powers built relations in the Middle East, particularly through the League of Nations after World War I. During the 1950s, the Cold War heightened concern about the Middle East. In 1965, U.S. policy towards the region changed, reflected in more lenient immigration laws as people fled political crises in Iran, Palestine, Lebanon, and Afghanistan in the 1970s.

These political crises, along with energy ties due to Middle East oil, impacted relations with the U.S. In the 1980s, President Carter announced what became known as the Carter Doctrine for the Middle East, which specified and integrated political, economic, and military efforts in the region and has served as the organizing principle for U.S actions in the Middle East ever since. This included concrete steps and plans, such as “‘domestic and international energy efforts; some tailored increase in defense spending and activity; and…support for other countries in the region.” The most important piece of the Doctrine was the “overarching U.S. aim to prevent ‘any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region,'” namely because of U.S. interests in Middle East oil at the time.

Iran

In the 1940s, British and Soviet troops occupied Iran. A communist plot to overthrow the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi failed in 1949, and was followed by tensions between him and the nationalist Prime Minister Mossadeq. After attempting to dismiss Mossadeq, the Shah was forced out of Iran. Based on fears of a communist takeover, a joint British-American operation in 1953 helped overthrow Mossadeq and returned the Shah to power.

Protests against the Shah forced him to flee to the U.S. in January of 1979 and Islamic religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile to assume power. Demanding the return of the Shah to stand trial in Iran, a group of Iranian students seized the American Embassy in Tehran in November of 1979 and held embassy personnel hostage for 444 days. The U.S. froze Iranian assets and severed diplomatic ties. Tensions remained and escalated amidst sanctions and mistrust of Iran’s uranium enrichment during the mid-2000s.

In 2013, Iranian President Rouhani and President Obama held the first phone conversation between the two countries since 1979. They began discussions for the eventual Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a controversial agreement “under which Iran agreed to curb its nuclear work in return for limited sanctions relief.” The U.S., Britain, China, France, Germany, and Russia reached the agreement in July 2015. The U.S. withdrew in May 2018. The JCPOA is discussed further below.

Lebanon

The U.S. first established diplomatic relations in Lebanon in the early 1800s, when Lebanon was part of the Ottoman Empire. American officials were evacuated in 1917 when the Ottoman Empire fell; relations were reestablished after World War I and strengthened in 1944 following official recognition of Lebanon’s independence. By the 1960s, the U.S. Embassy in Beirut was one of the largest in the Middle East and served as headquarters for a number of U.S. agencies in the region. This changed during Lebanon’s civil war, which lasted from 1975 to 1990, and when Israel invaded Lebanon to pursue a Palestinian splinter group, Abu Nidal, that attempted to assassinate the Israeli ambassador to Britain in 1982. In 1983, over 200 American marines, sailors, and soldiers were killed by a suicide bomber, and two attacks on the U.S. Embassy in 1983 and 1984 forced it to close. It reopened in 1990.

During the 1980s wars, a guerrilla group evolved into a major political party and military force known today as Hezbollah, which receives significant funding from Iran. According to the Counter Extremism Project, “Hezbollah has used its military strength, political power, and grassroots popularity to integrate itself into Lebanese society” and “has also created educational and social institutions that run parallel to the Lebanese state.” Hezbollah, but not the Lebanese state, is subject to international sanctions. Hezbollah’s military involvement in Syria with its close ally Iran “poses a growing asymmetric threat to the United States, Israel, Jordan, and other countries in the region” and complicates its position in Lebanon.

Israel and Palestine

After WWI, “the League of Nations entrusted Great Britain with the Mandate for Palestine,” based on the 1917 Balfour Declaration that “asserted the British Government’s support for the creation ‘in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.’” In May of 1948, the UN’s Resolution 181 divided the former British Mandate into Jewish and Arab states, and the city of Jerusalem remained under international control. The U.S. immediately recognized the State of Israel, but the “resolution sparked conflict between Jewish and Arab groups within Palestine,” leading to the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. Palestinian guerrilla groups based in Syria, Lebanon and Jordan increased tensions between Israel and its neighbors, including Egypt and Iraq, resulting in years of conflict: the Six Day War in 1967, the October 1973 Yom Kippur War, the 1982 invasion of Lebanon and the 2006 war with Lebanon.

Since the 1990s, the U.S. has engaged in helping facilitate a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 1994, Israel agreed with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to allow a Palestinian Authority (PA) limited rule over Gaza and certain areas of the West Bank, where the majority of Palestinians live. The PA still exercises this limited rule over areas of the West Bank, although Hamas, “a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization supported in part by Iran,” has had de facto control over Gaza since 2007. Conflict between Hamas and Israel keeps tensions high.

The following video dives deeper into the relationship between Israel and Palestine.

Saudi Arabia

The U.S. founded the Arabian American Oil company after oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1938. Saudi Arabia gradually bought out shareholders and the company has been wholly owned by the Saudi government since 1980. U.S. companies including Chevron and ExxonMobil still have refineries in Saudi Arabia. In 1981, in retaliation for U.S. support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War, Saudi Arabia participated in an oil boycott aimed at the U.S. and other Western nations. Despite these tensions, Saudi Arabia remained the primary U.S. ally in the region after Iran’s 1979 Revolution. In 1990, after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Saudi Arabia’s King Fadh invited U.S. troops to use Saudi Arabia as a base for operations against Iraq.

Saudi Arabia has also long been the top destination for U.S. defense sales. In recent years, many debate the continued sale of arms to Saudi Arabia since the nation intervened in Yemen’s civil war in 2015. Additionally, dissidents and activists have been arrested, prompting human rights criticisms. The most serious accusations came when the CIA concluded Saudi officials and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman were involved in the murder of Saudi journalist and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi, whose family has a long and complicated relationship with the Saudi Royal family.

Yemen

In 1990, the U.S.- and Saudi-backed Yemeni Arab Republic and the USSR-backed People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen united to form the modern Yemeni state. Ali Abdullah Saleh assumed leadership of the government, but later stepped down due to challenges from southern Yemeni movement Al-Hirak, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and the Houthi movement among Zaydi Shias in the north. The U.S. backed the 2013 UN-sponsored National Dialogue Conference “to formulate a new constitution agreeable to Yemen’s many factions,” but the conference ended “after delegates couldn’t resolve disputes over the distribution of power” and the interim government resigned under pressure after Houthi rebels seized power in September of 2014, setting off a civil war that has devastated the country and its people. The military split between the Houthis (with support from Iran) and the government forces (with support from Saudi Arabia). The U.S. backs the Saudi-led coalition.

The Associated Press explains Yemen’s civil war (4 min):

Afghanistan

In 1973, a military coup overthrew the country’s last king, brought the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan to power, and established the Republic of Afghanistan. In 1978, a member of the Afghan Communist Party seized control in another coup and rivalries grew among leaders. The USSR invaded Afghanistan to prop up the failing communist regime, prompting Mujahadeen (Afghan warlord rebels against the Soviet-backed government) to unite.

In 1979, the U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan was killed, and the U.S. stopped sending assistance to Afghanistan. By 1986, the U.S. was sending arms to the Mujahadeen. The U.S. signed peace accords with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Soviet Union in 1989, guaranteeing Afghan independence and the withdrawal of Soviet troops, but disputes between rival factions remained unresolved. In 1995, the newly formed Islamic militia, the Taliban, rose to power with promises of peace. The Taliban ruled according to traditional Islamic values, curtailed the rights of women, and enforced Islamic law “via public executions and amputations.” The United States did not recognize the Taliban’s authority.

In the aftermath of 9/11, the U.S. military began a campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. The Taliban government protected Osama bin Laden, but quickly lost control of the country before relocating across the southern border to Pakistan. The U.S. military maintained a presence in Afghanistan from 2001 and participated in a bilateral counterterrorism mission with Afghan forces. Peace talks were slow and plagued by continuous setbacks, and the Taliban eventually regained control of Afghanistan in the wake of U.S. troop withdrawal in August, 2021.

Kuwait

In August of 1990, Saddam Hussein led the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, instigating the Persian Gulf War. The U.S., along with Japan, the former Soviet Union, and most of Europe and the Middle East condemned the attack and joined to form a coalition. Operation Desert Storm brought an end to the war in March of 1991, when Kuwait was liberated.

Iraq

At the end of the Persian Gulf War, Iraqi forces surrendered, but Saddam Hussein did not relinquish power. In 1998, Sadam Hussein refused to cooperate with UN inspectors in Iraq to survey weapons programs. In March of 2003, the US-led coalition invaded Iraq in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Forces captured Saddam Hussein by December of 2003, and remained in the country to bring stability to Iraq. The final U.S. troops withdrew from Iraq in December 2011.

Fighting ensued quickly after troops withdrew, leaving a power vacuum in Iraq. In 2014, the al-Qaeda splinter group, ISIS, took control of Iraqi and Syrian territory and declared itself a caliphate. The territorial caliphate was declared defeated in March of 2019, but the group is still active and has claimed responsibility for terrorist attacks in the Middle East and around the world.

Syria

Syria has been on the U.S. list of state sponsors of terror since the list’s origin in 1979, based on “its continuing policies in supporting terrorism, its former occupation of Lebanon, pursuing weapons of mass destruction and missile programs, and undermining U.S. and international efforts to stabilize Iraq.” In 2011, the Assad regime’s brutality in response to protests sparked a civil war that has lasted more than seven years, and has been further complicated by the 2014 rise of ISIS. Along with the international community, the U.S. government has provided humanitarian and stabilization assistance to the displaced population and the Syrian opposition.

The Role of Government

U.S. foreign policy is crafted principally in the executive branch, with the White House setting the agenda and assembling a national security strategy. At the Cabinet level, the Secretaries of State and Defense also play key roles in shaping policy, determining priorities, and implementing strategy. The U.S. Foreign Service, under the aegis of the State Department, trains and employs our diplomats, who are posted at U.S. diplomatic missions throughout the world to carry out U.S. foreign policy.

In the legislative branch, lawmakers in the House and Senate do play an important role in foreign policy; elected representatives in Congress have Constitutionally-mandated responsibilities for foreign affairs, “including the right to declare war, fund the military, regulate international commerce, and approve treaties. At least as important are such congressional authorities as the ability to convene hearings that provide oversight of foreign policy.”

The following Congressional committees handle foreign policy, defense, and national security matters:

- House Foreign Affairs Committee

- House Armed Services Committee

- House Homeland Security Committee

- Senate Foreign Relations Committee

- Senate Armed Services Committee

- Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee

-

Goals of U.S. Policy in the Middle East

National Security and Diplomacy

Over the past few decades, the Middle East has experienced much upheaval . Uprisings across the region have “challenged autocratic governments,” “toppled longtime dictators,” and resulted in multiple civil wars, all of which have “left regional leaders intently focused on regime security,” Brookings Senior Fellow Tamara Cofman Wittes explains.

. Uprisings across the region have “challenged autocratic governments,” “toppled longtime dictators,” and resulted in multiple civil wars, all of which have “left regional leaders intently focused on regime security,” Brookings Senior Fellow Tamara Cofman Wittes explains.

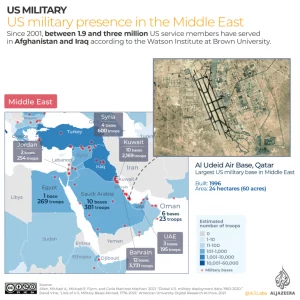

The U.S. has relied on a combination of intelligence cooperation, diplomacy, and military tools in the region. The Department of Defense divides U.S. troops around the world into eleven Unified Combatant Commands, each with its own commander. U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), which covers the Middle East, is commanded by General Michael E. Kurilla. The U.S. is also heavily involved in multinational endeavors, such as the Global Coalition to defeat ISIS. Senior Pentagon official James H. Anderson described to Congress in May 2020 that U.S. military presence in the Middle East was to “ensure the region is not a safe haven for terrorists, is not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and contributes to a stable global energy market.” Recent administrations have made efforts to recede from the region, but there are still concerns about how regional partners can stabilize the region and protect shared interests, and the costs are still large.

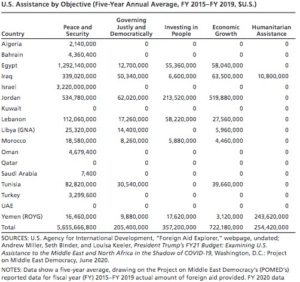

According to a report by the RAND Corp., the Middle East receives more than 50% of all U.S. global military aid, and of the roughly $6 billion in global foreign military financing apportioned in 2019, over 80% went to Israel, Egypt, and Jordan. The authors explain much of this is comes in the form of “[l]egacy aid packages and regional partnerships designed during the Cold War and the post-1990-1991 Gulf War eras, including massive arms packages to increasingly assertive Arab Gulf partners,” but very little attention is paid to nonsecurity investments.

Brown University’s Costs of War dives further into the details of spending and casualties resulting from the U.S.’s post-9/11 wars.

Economic and Trade Interests

The U.S. links its national security and economic goals, based on the idea that “economic development supported through enhanced trade and investment ties can advance U.S. goals of peace and stability” in the region. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative points to U.S. Free Trade Agreements with Jordan, Israel, Bahrain, and Oman, among others, as “context for U.S. trade investment policy dialogues with these governments, dialogues which are aimed at increasing U.S. exports as well as assisting in the development of intra-regional economic ties.” Economic sanctions are also part of this; U.S. sanctions on Iran “were at the core of Trump Administration policy to apply ‘maximum pressure’ on Iran” and compel Iran to renegotiate a new version of the JCPOA, although these “have arguably not, to date, altered Iran’s pursuit of core strategic objectives,” some experts note.

Arms sales are also a central component of U.S. economic relations in the Middle East; between 2013 and 2017, almost half of U.S. arms exports went to the region, primarily to Saudi Arabia as well as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. The U.S. is also Israel’s single largest trading partner, primarily in semiconductors and telecommunications equipment.

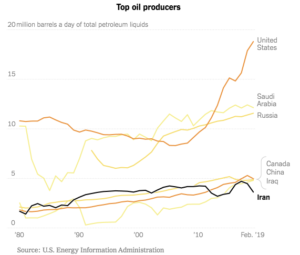

In terms of imports, foreign relations analyst Martin Indyk says the U.S. is no longer dependent on Middle Eastern oil as it has focused on its own domestic natural gas production, which means ensuring “the free flow of oil from the Persian Gulf area at reasonable prices” is still important but no longer “a vital strategic interest.” The U.S. has been the world’s largest natural gas exporter since 2018, and about 60% of U.S. oil imports come from Canada and Mexico; only 5% of oil imports to the U.S. come from Saudi Arabia.

Universal Human Rights

The State Department maintains that “a central goal of U.S. foreign policy has been the promotion of respect for human rights, as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

According to Amnesty International, across the Middle East “with virtually no exceptions governments have displayed a shocking intolerance for the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly.” Protesters and activists across the region from the United Arab Emirates to Palestine to Lebanon have been detained for criticizing authorities or peacefully demonstrating.

Civilians also suffer through armed conflicts in the region, particularly those caught in the civil wars in Yemen and Syria. Human Rights Watch reports that as of the end of 2021, over 4 million people are internally displaced in Yemen and more than 13.4 million Syrians are in need of humanitarian assistance, with 1.48 million in “‘catastrophic'” need. The Global Coalition seeks to stabilize areas liberated from ISIS in Iraq and Syria, but the US-led offensive against ISIS in Raqqa has also been accused of causing far more civilian deaths than had been acknowledged.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Allies

Maintaining strong alliances in the Middle East is central to U.S. objectives of ensuring stability in the region. Allies include the Gulf Cooperation Council, a regional organization founded in 1981 that seeks to coordinate and connect its members’ political and economic issues. Members include the Kingdom of Bahrain, the State of Kuwait, the Sultanate of Oman, the State of Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The U.S. and the E.U. have looked to the council for trade and defense opportunities, but regional upheaval has strained relations among members. Oman in particular, however, has been cultivating diplomacy in the region.

Maintaining strong alliances in the Middle East is central to U.S. objectives of ensuring stability in the region. Allies include the Gulf Cooperation Council, a regional organization founded in 1981 that seeks to coordinate and connect its members’ political and economic issues. Members include the Kingdom of Bahrain, the State of Kuwait, the Sultanate of Oman, the State of Qatar, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The U.S. and the E.U. have looked to the council for trade and defense opportunities, but regional upheaval has strained relations among members. Oman in particular, however, has been cultivating diplomacy in the region.

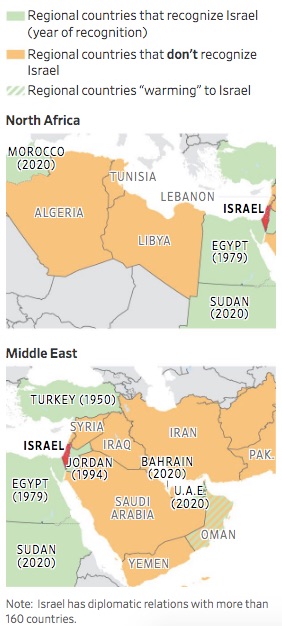

The State Department says that Israel “has long been, and remains, America’s most reliable partner in the Middle East.” Israel and the U.S. signed a free trade agreement in 1985 and participate in joint military exercises, military research, and weapons development. The two also work together through the Joint Counterterrorism Group, “the State Department’s longest running strategic counterterrorism dialogue.”

In Lebanon, the U.S. seeks to “help preserve its independence, sovereignty, national unity, and territorial integrity.” The U.S. is Lebanon’s primary security partner; it supports state institutions by providing bilateral foreign assistance to Lebanon to counter the influence of Hezbollah, which is largely funded by Iran, as well as that of ISIS near Lebanon’s border with Syria.

In 2018, the U.S. and Jordan signed a “non-binding Memorandum of Understanding” that made the U.S. Jordan’s single largest provider of bilateral assistance, which is used for development, education, infrastructure, agriculture, and humanitarian aid to communities in Jordan that host refugees from Syria.

The U.S. and Saudi Arabia generally share the same goals of “regional stability and containing Iran,” but disagreements surrounding regional conflicts and human rights violations have raised tensions. The two countries also have a strong economic relationship; the U.S. is Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner, particularly in arms sales, and Saudi Arabia is the U.S.’s leading source of imported oil from the region.

The Republic of Turkey, which is partly in Europe and partly in the Middle East/Asia, has been an American ally and member of NATO for more than 70 years. Turkey hosts two major U.S. air force bases that are strategically important for U.S. military operations in Iraq and Syria, Turkey’s southern neighbors. In recent years, tariffs, Turkey’s ties to Russia, and diverging policy priorities and perspectives have put some strain on its U.S. relationship.

U.S. troops maintained a presence in Iraq from the US-led invasion in 2003 until 2011. By 2013, sectarian violence and the rise of ISIS plagued the state, which prompted the Obama administration to re-deploy troops to assist the Iraqi Army. The U.S. has designated Iraq “as a beneficiary developing country under the Generalized System of Preferences program,” through which a number of U.S. companies are involved in Iraq’s energy, defense, information technology, and transportation sectors. Iraq is the second leading source of U.S. imported oil from the Middle East.

The Kurds for a distinctive ethnic community without an independent country. Large Kurdish minority communities live in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Kurdish militias attracted international attention when they led grounds force to defeat the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. The Kurds have been key American partners in building a democratic Iraq since 2003, and in Syria, Kurds comprise a significant portion of the Syrian Democratic Forces that are U.S. allies fighting in Syria’s civil war.

Afghanistan was an important partner countering terrorism and was designated a Major Non-NATO ally of the U.S., until August 2021 when the Taliban regained control of the country.

Threats

The U.S. has not had diplomatic relations with Iran since the U.S. Embassy in Tehran was seized in 1979 during the Iranian Revolution, after which Iran “ground[ed] its identity and legitimacy in anti-Americanism.” Currently, the U.S. and Iran support opposing sides in several regional conflicts, including in Syria (the U.S. supports the Syrian Democratic Forces and Iran supports the Assad regime), Yemen (the U.S. has supported the Saudi-led coalition and Iran has reportedly supported the Houthi rebels), and Lebanon (Iran supports Hezbollah). Iran also poses a threat through its nuclear development program and missile program, which has prompted the U.S. to impose a number of sanctions.

Hezbollah, the Lebanon-based militia, and Israel continue to militarily engage with each other, creating another site of conflict in the region. Hezbollah’s ties to Iran also pose a threat; one analysis from May 2018 noted that if the “Israel-Iran conflict in Syria worsens and Iran feels cornered, it could look to gain leverage over Israel by having Hezbollah launch attacks from Lebanon.” Hamas in the Gaza Strip also poses a threat to Israel, as it refuses to recognize Israel and still engages in violence despite a reconciliation agreement with rival political group Fatah in 2017.

In the aftermath of 9/11, the U.S. military began a campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. The Taliban government protected Osama bin Laden, but quickly lost control of the country before relocating across the southern border to Pakistan. For almost 20 years, they “waged an insurgency against the Western-backed government in Kabul, international coalition troops, and Afghan national security forces.” The Taliban regained control of Afghanistan in the wake of U.S. troop withdrawal in August, 2021.

ISIS formed in 2013 as an al-Qaeda splinter group, and controlled large swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria in 2014. U.S-backed Iraqi forces and Syrian Democratic Forces regained territory until the territorial caliphate was declared defeated in March of 2019. Despite the loss of physical territory, ISIS remains a global threat as it maintains a presence throughout the Middle East and Northern Africa and has inspired or claimed responsibility for lone-wolf attacks around the world, including in Turkey, Morocco, Lebanon, Indonesia, the Philippines, France, Belgium, and Sri Lanka.

Troop Withdrawal

Brookings Fellows Bruce Riedel and Michael E. O’Hanlon estimate there are roughly 60,000 U.S. troops in the Middle East, a significant decrease from the more than 150,000 based there during the Bush and early Obama administrations.

The dilemma of withdrawing troops from Afghanistan sums up the broader regional challenge. Following a Trump administration agreement, the Biden administration announced that all U.S. troops would withdraw by September 11, 2021, with foreign troops under NATO command withdrawing in coordination. Some military officials expressed fear this would “suspend what amounted to an insurance policy for maintaining a modicum of stability in the country,” and undermine security in the country. Others maintained U.S. military presence over the past two decades failed to end the conflict and it was time to refocus the national security policy to emphasize humanitarian and diplomatic support for Afghanistan.

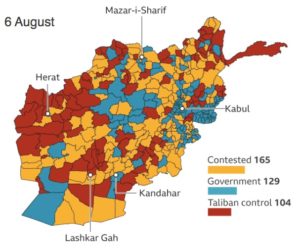

By mid-August 2021, Taliban forces overpowered Afghan National Security Forces and took over the capital, Kabul, resulting in the collapse of the government much faster than anticipated. “Within hours, Afghanistan’s Washington-backed president had left the country and the flag at the U.S. Embassy had been lowered amid a hasty evacuation of diplomatic personnel.” See how quickly the Taliban advanced with the control maps below, 10 days apart.

According to Robert Satloff of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the disorder in the region “limits how much the United States can shape its trajectory, no matter how much it invests.” Many also point out aggression and attacks against U.S. forces in the region as a reason to withdraw; in January 2022, for example, multiple military bases housing U.S. troops in Iraq and Syria were attacked by Iran-backed militias. They argue continued U.S. troop presence “invites danger.” Even so, the Middle East remains “an arena of fierce geopolitical competition,” and the challenge facing the U.S. in any attempts to withdraw is relying on regional partners to protect shared interests. Additionally, the U.S.’s so-called pivot to Asia to some extent has the potential to shift resources currently in the Middle East toward Asia. See The Policy Circle’s Foreign Policy: Asia Pacific Brief for more.

Human Rights

Saudi Arabia

In a March 2019 hearing to appoint a new ambassador to Saudi Arabia, both Republican and Democratic Senators called out “Riyadh’s role in the Yemen war” and the “detention and torture of women’s rights activists.” Saudi Arabia also faced international backlash after the death of Jamal Khashoggi, the Washington Post columnist with ties to the Saudi Royal family who was killed at the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. A UN report released in June of 2019 claimed “Saudi Arabia is responsible under international human rights law” for the death of Khashoggi, and that the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman should be investigated over the murder. In February 2021, a U.S. intelligence community assessment confirmed the Crown Prince’s direct involvement.

Yemen

The U.N calls the conflict in Yemen between the Houthi rebel movement and the Saudi Arabian-led coalition the worst humanitarian disaster in the world. Currently, the U.S. supports the Saudi-led coalition with intelligence and training. Lawmakers have long expressed concern for the civilian deaths in Yemen that have largely been attributed to Saudi airstrikes. At the same time, Saudi and Yemeni officials have said indications that the U.S. is withdrawing support “appear to have emboldened Houthi fighters.” The WSJ reported that the Houthis launched more drone and missile strikes in February 2021 than any other time in the six-year civil war.

Anthony H. Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies notes it is unclear that either the government or Houthis “could have any real competence in administering and large, highly populated state of more than 30 million people with few resources,” or would know how to deal with a humanitarian crisis affecting 14 million people and unite the country into stable peace.

The Council on Foreign Relations explains the crisis in Yemen (2:30):

Iran

In Iran, 2018 was designated the “year of shame” after authorities arrested over “7,000 protesters, students, journalists, environmental activists, workers and human rights defenders, many arbitrarily.”

Iran

Nuclear Threat

The international community did not believe Iran’s nuclear program was peaceful, even though Iran said it was. In 2015, under the Obama administration, Iran, the European Union, and the permanent U.N. Security Council members (the United States, the United Kingdom, China, France, and Russia plus Germany) negotiated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), an agreement to limit Iran’s nuclear activities in return for eased economic sanctions.

The JCPOA was highly controversial and received bipartisan criticism. Primary criticisms were the fact that the JCPOA allowed Iran to continue some nuclear activities, did not address Iran’s missile development, offered Iran sanctions relief on a wide array of activities in exchange for restriction of only one area (nuclear capabilities), and that the sanctions relief was indefinite while many of the nuclear restrictions were limited to a number of years. Advocates argued that without the agreement, Iran could continue its nuclear activities unchecked, and that having an agreement in place would improve the overall security of the region and would open the door for the U.S. and its allies to deal with other security threats from Iran.

For an overview and timeline of Iran’s nuclear activities, see CNN’s “Iran’s Nuclear Capabilities Fast Facts.” The videos below explain more about the nuclear agreement.

The Trump administration officially withdrew U.S. participation in May 2018, “citing a lack of progress limiting Iran’s nuclear weapons development program and a failure to adequately deal with Iran’s missile program.” Iran’s “ballistic missile program and support for terrorism and for regional actors like the Syrian government, Hezbollah and Hamas” have also been areas of increasing concern.

In retaliation, Iran has since been “scaling back curbs to its nuclear program,” prompting Britain, France, and Germany to formally accuse Iran of violating the terms of the JCPOA. Ongoing efforts to bring Iran and the U.S. back to re-negotiate the JCPOA “to limit Iran’s uranium enrichment in exchange for relief on sanctions” have continued to hit roadblocks. The U.S. maintains Iran must reverse its uranium enrichment violations first, while Iran says the violations are in response to the U.S. withdrawal and sanctions need to be lifted first.

U.S. political scientist Ian Bremmer explains the political intricacies of renegotiating the deal (3 min):

Escalating Tensions

U.S. sanctions on Iran have succeeded in restricting Iran’s government and economic growth, but have failed to change Tehran’s behavior.

U.S. sanctions on Iran have succeeded in restricting Iran’s government and economic growth, but have failed to change Tehran’s behavior.

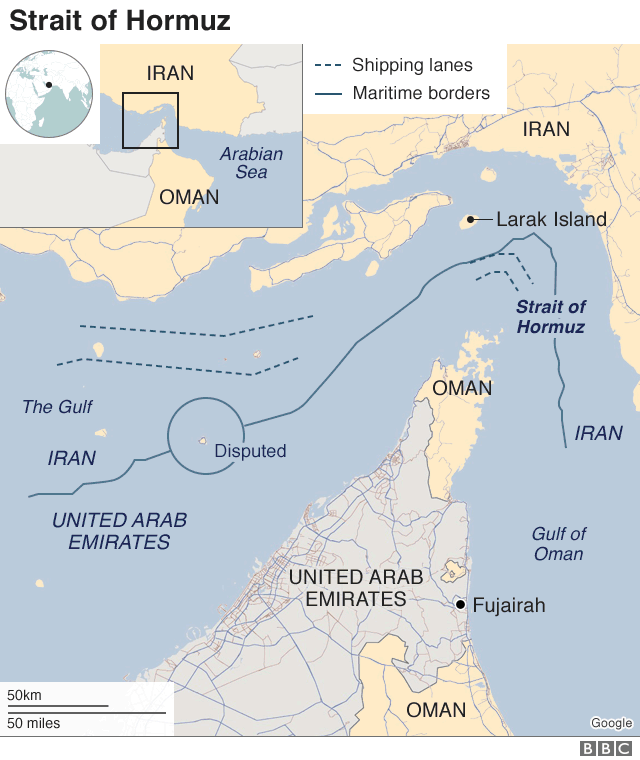

Tensions escalated in 2019, including attacks on oil tankers, a shot down U.S. surveillance drone in the Strait of Hormuz, and increased sanctions on Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, blocking Iran’s leadership access to the U.S. financial system. For more on conflict in the Gulf of Oman’s waterways, see the Council on Foreign Relations’ backgrounder on the Strait of Hormuz and this video from The Wall Street Journal. Tensions continued into 2020, after an American contractor was killed at an Iraqi military base and a drone strike killed Iran’s top general Qassem Soleimani. Since, Iran has targeted Iraqi bases where U.S. troops have been stationed and has admitted to accidentally shooting down a commercial plane bound for Ukraine from Tehran.

Peace Efforts and Stability

Afghanistan

The U.S. spent over $840 billion on the war in Afghanistan while it maintained troop presence in the region, but hopes of peace agreement between Taliban representatives and the Afghan government ended when the Taliban regained control following U.S. troop withdrawal in August 2021.

The U.S. and other nations evacuated over 100,000 people out of the country, including Americans and Afghan citizens who aided the U.S., such as interpreters, but many were left behind and are still seeking refuge. The UN reports Afghanistan has the third-largest displaced population in the world, with women and children making up 80% of those displaced. The country’s economy is also in shambles; throughout the war, almost 40% of Afghanistan’s income came from foreign aid. Most nations, the U.S. included, suspended foreign aid after the Taliban takeover.

The Taliban announced in September 2021 its interim government, comprised of senior members, many of whom are on U.S.-designated terror lists. Whether there will be a permanent government or elections in the future remains to be seen, as does treatment of civilians. Women are fearful of a return to Taliban control, and Taliban fighters have responded with violence to protests around the country. For a deeper dive on the Taliban, see The Policy Circle’s Terror Groups and Rogue States Brief.

Syria

Since the rise of ISIS in 2014, the U.S. worked with the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, which saw the territorial defeat of ISIS in Syria in March 2019. In December of 2018, President Trump announced the immediate withdrawal of troops from Syria, although defense officials wanted to first guarantee the security of the U.S.’s Kurdish allies as well as address the 20,000 ISIS detainees in northeast Syria. Troops left Syria at a slow and staggered pace, and a few hundred remain in early 2021.

Since the rise of ISIS in 2014, the U.S. worked with the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, which saw the territorial defeat of ISIS in Syria in March 2019. In December of 2018, President Trump announced the immediate withdrawal of troops from Syria, although defense officials wanted to first guarantee the security of the U.S.’s Kurdish allies as well as address the 20,000 ISIS detainees in northeast Syria. Troops left Syria at a slow and staggered pace, and a few hundred remain in early 2021.

In the northwest region, one of the last areas outside of government control, Russia and Turkey had negotiated a cease-fire between the Syrian rebels and government forces in June of 2019, but bombing and shelling resumed only days later.

Lt. Gen. Paul Calvert, commander of the US-led counter-ISIS mission in Iraq and Syria, has said “the volatile cultural and political conditions” in Syria remain a concern, saying American troops have sometimes only narrowly “avoided clashes with Russian combat troops, Syrian troops, and even its NATO-ally Turkey.”

Israel and Palestine

Israelis and Palestinians are caught in the Arab-Israeli conflict in the West Bank and Gaza. A June 2018 U.N. General Assembly resolution condemned both Israeli actions against Palestinian civilians as well as the firing of rockets from Gaza against Israeli civilians by Palestine.

In a break from previous policy and international consensus, the Trump administration recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December of 2017 and moved the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in May of 2018. The decision was “greeted warmly by Israel but rejected by Palestinians and many other international actors.”

“Arab states have historically refused formal diplomatic ties with Israel while its conflict with the Palestinians remains unresolved,” but Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Sudan, and Morocco all agreed to normalize relations with Israel in 2020, mainly due to “shared security interests and deals brokered by the Trump administration.”

The Future of U.S. Policy in the Middle East

“The challenge for American policy is how to protect its remaining and still important interests in [the Middle East] in an era of austerity and fierce power competition,” says Brookings Senior Fellow Tamara Cofman Wittes. The region is experiencing uprisings and civil wars along with governments that provide financial, material, and political support for armed actors because they see “civil conflicts as proxy wars with their regional rivals for the future regional order.” This means relying more on regional partners to stabilize the region may be difficult, as many say the presence of U.S. forces has been “an insurance policy for maintaining a modicum of stability.”

Others say the U.S.’s current reliance on military force has not worked for the past two decades, and the overall policy in the region needs to be reconsidered. The Middle East is no longer as central a concern to U.S. national security as it once was, particularly because the U.S. is no longer dependent on oil from the region. Steven Simon of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and Richard Sokolsky of the Carnegie Endowment argue that “‘the main threats to regional security and stability [in the Middle East] are internal, stemming from state weakness and dysfunctional governance; U.S. military forces are ill-suited to address these sources of conflict.'”

A report by the RAND Corp. recommends reviewing the costs and benefits of a large military footprint in comparison to a focus on “economic and societal grievances that provide a ready pool of recruits” to counter terrorist groups like ISIS, including health, unemployment, and human rights abuses. Particularly as Russia and China become more economically involved in the region, the U.S. will need to reconsider its security cooperation, economic assistance programs, diplomatic engagement, and ensure these efforts are effectively achieving intended outcomes.

Conclusion

The U.S. economic, national security, and diplomacy interests in the Middle East are greatly affected by terrorism, civil wars, and general instability in the region. Maintaining strong relationships with allies and understanding the nature of conflicts is key to achieving U.S. foreign policy goals in the region.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out how your state and district are affected by foreign policy.

- Are there many veterans in your city or community?

- Does your city or community have a large immigrant population? Search on your state or municipality’s website for a community or human services tab, or search for terms such as “immigration,” in the search bar.

- Search on your state or municipality’s website for the business portal using keywords such as “trade,” or look for a tab labelled “business” in a dropdown menu. Look for options such as “access to world markets,” “importing and exporting,” or “[your state] + international trade,” or search for any of these terms in the search bar.

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

- Does one of your representatives serve on one of the Congressional committees addressing foreign affairs?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Keep track of bills in Congress related to the Middle East.

- Know who decides policy in the Middle East: Stay up-to-date with information from the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

- The Office of Legislative and Intergovernmental Affairs is the point of contact for state and local governments at the International Trade Administration. See if your city or state has companies that engage internationally.

- If possible, organize a community discussion about aid, foreign policy, and what your tax dollars are going to support in foreign countries.

- Brown University details the Costs of War in terms of spending and casualties.

- Pose any questions in a written piece for your local publication to make others in your community aware and seek answers.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Foreign Policy: The Middle East? Consider exploring the following: