Introduction

Since European settlers first colonized what we now know as the United States, communities of faith have been at the heart of the social bonds that tie Americans together. These bonds have evolved differently across the nation, influenced by distinct regional cultures that have given rise to diverse forms of civic and religious life. From the Pilgrims at Plymouth to the settlers at Jamestown, who erected one of the first church buildings in North America, to the establishment of Jewish congregations in the 17th and 18th centuries, to Muslim communities building faith-based non-profits and Hindu leaders volunteering to boost civic participation, religion has animated much of our civic life. “Historically, religious institutions have been of primary importance in creating and maintaining extra-familial social ties and dense community networks,” says a 2017 report issued by the Senate Joint Economic Committee. Today’s political polarization, a national epidemic of loneliness, and fragmented civic life underscore the continuing importance of faith to strengthen the fibers of our shared civic ties.

Throughout American history, religious congregations—first churches, then synagogues, mosques, and temples—have been hubs of vibrant communal life and civic engagement. Religious freedom and shared faith have brought Americans together to organize, advocate, and serve, fostering reciprocity, trust, and cooperation. The story of American civic life-enhancing community quality through political and nonpolitical means—is intertwined with the history of American faith traditions. In recent decades, dropping rates of religious affiliation among Americans have coincided with declines in civility, civic engagement, and public service.

As our pews have emptied, we’ve become socially disconnected, communally distrustful, and civically disengaged. Without strong social bonds to bridge political differences, public policy disagreements now divide Americans more than at any time in recent memory, casting a cloud of civic anomie—characterized by a lack of norms and a breakdown of social cohesion—over the national political scene. The foundations of our diverse, pluralistic democracy are strained.

The decline in civic participation since the mid-20th century coincided with a decrease in “social capital,” which Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam defines as the social connections that form naturally and the normal, expected reciprocity and trust that grows from them. As these networks fray, their norms decay, leading to a less trusting, less connected society. This erosion hinders our ability to work together for the common good, flourish under limited government, and prosper economically.

To understand the particular importance of social fabric and social capital in the United States, we must first understand the assumptions and beliefs that animated the nation’s founders. The Framers who laid the foundations of our constitutional order did so in a particular context, a moment in religious and political history that shaped their aims, concerns, and approach to government.

Putting it in Context

Before the Enlightenment, governments profoundly influenced what are now considered private matters, such as religious beliefs and social status. Civil society, now distinct from the government, was once entwined with state interests. Thinkers like John Locke advocated for limited government, emphasizing individual freedom in matters of conscience and belief.

The American Founders embedded this principle of limited government in the U.S. Constitution, fostering robust civic associations. Harvard sociologist Theda Skocpol notes that after British rule, a democratic civil society flourished, with voluntary groups rising from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War. When the young French writer Alexis de Tocqueville visited in the 1830s, he admired Americans’ ability to form associations of their own accord, contrasting this with European reliance on government or aristocracy. He observed that grassroots involvement was crucial for democratic governance.

Parallel to this story of civil society, the Enlightenment also ushered in significant changes to the religious landscape of the Western world. With the commencement of the Protestant Reformation in the early 16th century came a period of heightened religious persecutions and a century of intense religious wars within European Christendom. However, with the Enlightenment came the idea of religious tolerance from thinkers like John Locke.

In pre-Revolutionary America, Catholics and other religious minorities were afforded only limited protections of their religious freedom. They faced social stigma, discrimination, and legal strictures like religious tests for office. However, during and after the Revolution, the Enlightenment principle of religious liberty advanced. In 1791, the Bill of Rights was ratified, and all Americans were guaranteed free exercise of religion according to their own conscience. In the more than two centuries since, the United States has embraced a greater diversity of religious beliefs, and religious liberty has, albeit imperfectly, protected Americans of minority faiths to practice their religion according to their conscience.

This burgeoning religious freedom paved the way for religiously inspired civic engagement, exemplified by the late 19th and early 20th-century immigrant-aid charities. The Salvation Army, for instance, made significant societal contributions by aiding “the poor, the homeless, the hungry, and the destitute.” As waves of immigrants arrived in America from Europe and Asia, immigrant aid societies provided essential support, including translation services, food, clothing, religious comfort, legal assistance, temporary housing, loans, and job placement. Volunteers from religious groups and organizations like the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the Roman Catholic Church’s St. Raphael’s Society, and the National Council of Jewish Women all played a significant role in this effort. These groups, and others like them, aided millions of newcomers to the United States.

By the late 19th century, during the Gilded Age, civic and church involvement declined amidst rising inequality and political polarization. Yet, the first half of the 20th century witnessed a resurgence in civic and religious participation, peaking in the late 1950s and early 1960s with increased trust and rising marriage rates among young Americans. This trend, however, began to wane by 1960.

According to Putnam, religious institutions are pivotal in fostering community connection and social solidarity in America. About half of all group memberships are religious, significantly contributing to philanthropy and volunteering. Skocpol notes that churches facilitate unique interactions across different social strata, blending family life with civic activities and promoting values-based discussions, which are essential to democratic engagement.

This idea is further explored in the 2023 documentary Join or Die, which delves into the importance of social organizations, including religious institutions, in building a cohesive and engaged society. Watch the trailer for Join or Die (3 min):

Case Study: Black Pastors United for Education (BPUE)

In the 21st century, religious institutions continue to play an essential role in addressing some of society’s most pressing issues. Consider the religious organizations in your community. Even in small towns, there are likely various Christian congregations. Some areas are home to a rich diversity of faiths, each with its own network of volunteer opportunities, charity work, and social gatherings. Where there’s a parish, mosque, temple, or synagogue, you will likely find social capital and civic involvement.

In 2021, Pastor Joshua Robertson recognized the pressing issues of rising crime, violence, and declining academic performance among youth in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. In response, he and The Rock Church founded Black Pastors United for Education (BPUE) and established The Rock City Learning Center. The center provides a secure space for students aged 7 to 18 to focus on their education and connect with peers. This service became especially crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic when traditional schools were closed.

Inspired by Pastor Josh’s own academic challenges and the transformative power of mentorship, the center meets the diverse needs of its students and helps them reach their full potential. During the 2021-22 academic year, the center documented significant academic successes: ten students achieved a 90% average, twelve maintained an 80% average, and two showed substantial progress with a 60% average. These results underscore BPUE’s commitment to nurturing academic and personal growth and setting a standard for educational excellence.

BPUE is a coalition of pastors and congregations focused on educating under-resourced children using non-traditional learning spaces. This bipartisan organization works as a non-religious entity to secure resources and partnerships to assist communities in need. They aim to cultivate passionate communities dedicated to enhancing educational opportunities for a global impact.

Although BPUE works in non-religious ways, Pastor Josh’s motivation is deeply rooted in his faith. As he puts it, “I believe in the fundamental dignity of humanity. I believe people want other people to succeed and pursue greatness. I believe all God’s children deserve freedom and opportunity.”

The Rock City Learning Center continues a long-standing American tradition of faith groups addressing educational gaps in America. Historically, many of America’s earliest colleges were founded by religious institutions, aiming to educate clergy and laypeople. For instance, the Puritans established Harvard University in 1636, and Princeton University originally trained Presbyterian ministers. Catholic schools have provided access to education across diverse communities, including immigrant and low-income families. The Quakers, or the Religious Society of Friends, have played a notable role, primarily driven by their foundational beliefs in equality, peace, and integrity. Episcopal schools have similarly contributed to the educational landscape, focusing on inclusivity, service, and leadership. Watch Pastor Josh talk about BPUE (1 min):

By the Numbers

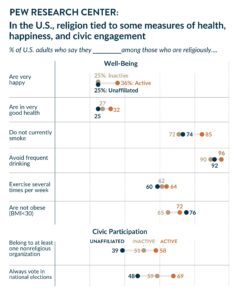

Religious faith has been a source of civic health and social solidarity throughout American history. Recent polling data and social science scholarship have quantified the importance of religion both to the lives of people of faith and the nation as a whole. A 2019 Pew Research Center report found that active members of religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged than religiously unaffiliated or inactive members.

In the United States, religiously active Americans report higher happiness, greater involvement in nonreligious organizations, and more consistent democratic participation. The report also notes that religious communities provide meaning and social capital, fostering purposeful lives and stronger community connections.Likewise,

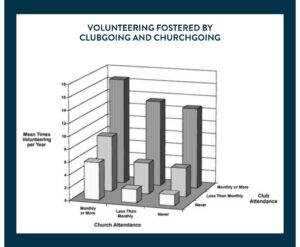

Volunteering rates fostered by clubgoing and churchgoing, adapted from Bowling Alone by Robert Putnam, p. 120 Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Robert Putnam finds that higher rates of churchgoing and participation in community or social clubs correspond with more volunteering. Those Americans involved on at least a monthly basis in both a church congregation and a community or social club volunteer several more times per year than those who are not. Putnam also argues that involvement in religious or secular organizations better predicts charitable giving than financial means.

Faith communities also pass on their civic virtues to their children. In a 2024 meta-analysis, researchers found that private schools outperform their public counterparts in instilling the values of political tolerance and political knowledge and that religious private schools are particularly associated with “positive civic outcomes.” Similarly, a 2017 literature review concludes that private school choice programs lead to comparable or improved outcomes for tolerance, civic engagement, and social order. EdChoice, a nonprofit institute that researches education policy, summarizes the findings of 11 studies on private school choice and civic values this way: “The research on private school choice programs shows they can help establish and strengthen civic norms and practices that are foundational to sustaining good citizenship, civil society, and representative democracy.”

Yet over the past 30 years, church attendance rates have dropped as the share of Americans professing no religious preference and reporting no religious attendance has risen. This drop in religious affiliation has correlated to an onset of civic malaise across various metrics.

According to Pew, 58% of adults in the United States who are active in their religious faith participate in one or more nonreligious voluntary organizations. Pew lists charity groups, sports clubs, and labor unions as examples. In comparison, 51% of adults who are not active in their faith and only 39% of adults without a religious affiliation engage in similar activities.

Why it Matters

Another factor contributing to this civic malaise may be a decrease in trust due to declining social capital. Decaying social and civic ties to one’s neighbors, in turn, erodes a widespread culture of trust and reciprocity. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama observes that trust fosters collaboration and strengthens organizations, making “social capital… a more important determinant of societal success than physical capital or access to information.”

Trust is particularly relevant in education, civics, and voting, where it helps shape policies and community cohesion. Faith-based groups play a pivotal role in these areas, driving initiatives that enhance civic involvement and trust among citizens. As civic participation declines and political polarization rises, faith becomes even more crucial in reinvigorating civic engagement and nurturing the trust essential for democracy.

Trust is particularly relevant in education, civics, and voting, where it helps shape policies and community cohesion. Faith-based groups play a pivotal role in these areas, driving initiatives that enhance civic involvement and trust among citizens. As civic participation declines and political polarization rises, faith becomes even more crucial in reinvigorating civic engagement and nurturing the trust essential for democracy.

Faith also influences the political landscape through religious voting blocs and advocacy groups that unite voters around shared values and morals. These groups shape electoral outcomes, policy decisions, and political discourse by mobilizing members around religious, social, and ethical principles, and they are becoming a significant force in American politics. The role of voting blocs highlights the significant democratic engagement of faith communities in shaping policy and advocating for values-driven reforms.

Voting blocs and advocacy groups are two more examples of the kinds of voluntary associations Alexis de Tocqueville described. Returning to Tocqueville’s observations in the 19th century can help us identify the institutions of civic life we see around us today.

Faith in Action: Contemporary movements in Civic Life

Tocqueville’s insights into Americans’ propensity to form religious and secular associations remain relevant today. In his seminal work Democracy in America, he observed that voluntary associations were a hallmark of American democracy and distinguished it from European societies. Civic groups and religious associations were crucial in promoting civic ideals and community. This inclination toward collective action has continued to shape the fabric of American civic and community engagement.

Faith-based organizations support civic ideals and have historically played a crucial role in expanding educational opportunities. They have been instrumental in establishing schools, particularly in underserved areas, thus contributing significantly to the educational landscape of the United States. This historical commitment to education exemplifies the ongoing contribution of faith-based organizations to societal development, highlighting their enduring impact on community growth and the promotion of equal access to education for all.

Modern faith-based initiatives addressing social challenges, from homelessness to foster care and more, exemplify the staying power of this American cultural trait. During the Civil Rights Movement, religious organizations and leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., used faith-based principles to advocate for justice and equality, mobilizing activists and communities.

More recently, faith groups have been instrumental in addressing challenges such as foster care and refugee resettlement. Safe Families for Children, for example, connects church members with community members to build a social support network for parents facing isolation, helping to prevent child abuse and neglect, reducing child welfare system entries, and enabling the child welfare system to focus resources on children and families in critical need. Global Refuge, formerly Lutheran Immigration Services, provides comprehensive aid to immigrants, including resettlement assistance for refugees and support for asylum seekers.

Additionally, faith communities and religious organizations offer such services as food banks, health services, and English as a Second Language classes. These civil associations are a vital form of political and social organization that decentralizes power and enhances democratic governance by engaging ordinary citizens in community affairs. One example of a faith-based non-profit providing comprehensive services is City Impact San Francisco, which provides food security, meals, a school, after-school programs, and health services.

Launched in 1984 and inspired and built on founder Roger Huang’s Christian faith, City Impact not only provides a safety net but also has a comprehensive impact on the city’s Tenderloin District residents. Learn more about City Impact and its neighborhood (2 min):

The Role of Government

Networks of civic associations serve as “mediating institutions”—structures of connection that bridge the gap between an individual’s private life and the public life of the government. In modern society, where the government’s role is narrower than it was in the time before thinkers like John Locke, space exists between each individual and the affairs of the state. Mediating institutions occupy this space. In Western countries today, the government no longer imposes religious requirements or norms of hierarchy and propriety as it once did. Yet the government still has a purpose in this “in-between space.”

In a modern, pluralistic democracy with multiple religious faiths, the government has an important role in safeguarding religious freedom while maintaining neutrality and not endorsing any particular religion. Support for faith-based initiatives varies across local, state, and federal levels, each contributing significantly to integrating religious organizations into public service. Cities like Philadelphia and Detroit collaborate with faith-based groups to address local challenges such as poverty and racial tensions through dialogue and cooperation.

At the state level, Montana’s Office of Faith and Community-Based Services, established in 2022 by Governor Greg Gianforte, promotes collaboration between the state and faith-based groups to tackle issues like addiction, foster care, and mental health. At the federal level, the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, initiated by President George W. Bush, aims to coordinate the federal government’s efforts to work with faith-based and neighborhood organizations to address various social issues and challenges.

In addition to partnering with faith-based groups, the government also plays a role in protecting the religious freedom of organizations that address pressing social issues.

When Americans discuss First Amendment protections of religious liberty or the relationship between religion and government, the phrase “wall of separation between church and state” often arises. This phrase originates from an 1802 letter by President Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist congregation in Connecticut concerned about state-established churches. Jefferson’s phrase can cause confusion, as some mistakenly believe it is part of the actual text of the First Amendment.

Over the past two centuries, the United States Supreme Court has taken up several cases to clarify the First Amendment’s meaning, but the issue remains contested. “The debate about the ‘wall’—whether it exists and, if so, where it should stand and how high it should be—continues to this day,” notes the Bill of Rights Institute.

The U.S. Supreme Court regularly reviews the interplay between government support and constitutional principles, especially in cases related to the Free Exercise Clause, which protects the freedom to practice religion, and the Establishment Clause, which prohibits the government from establishing an official religion. These cases highlight the constitutional limits and freedoms related to religious activities in civic life.

Legal Frameworks and Supreme Court Cases

View the following videos to better understand the complexities of church-state separation and the judicial scrutiny required to uphold the First Amendment.

1. Establishment Clause of the First Amendment: This video delves into the history and Supreme Court interpretations of religious freedoms, clarifies common misconceptions, and highlights ongoing judicial efforts to balance religious freedom with constitutional limits. (The Bill of Rights Institute, 8.5 minutes).

2. The Free Exercise Clause: An explanation of this clause in the Constitution and its role in protecting religious freedoms against government interference (The Bill of Rights Institute, 6 minutes)

3. The Lemon Test and Lemon v. Kurtzman: The Lemon Test, established by the landmark Supreme Court case, provides a concise overview to assess whether a law violates the Establishment Clause. (The Federalist Society, 2 minutes).

Faith-Driven Enterprises: Fostering Civic Engagement and Community Development

Private enterprise is another institution that can play a significant role in the interplay between faith and civic life. Faith-inspired business policies can significantly enhance employee well-being, and companies like Chick-fil-A and Hobby Lobby, which close on Sundays, exemplify this approach. These companies foster better mental health and work-life balance by allowing employees to observe religious practices and spend time with their families. A Harvard Business School study has shown that such policies enhance productivity and boost overall firm performance, highlighting the benefits of integrating well-being into business models.

Other businesses like Musee Bath and revenue-generating non-profits such as Care Portal demonstrate how religious beliefs can shape business practices that benefit people. Though Musee Bath is not explicitly faith-based, it operates under a business model deeply inspired by the faith of its founder, Leisha Pickering. The company’s commitment to creating products that enrich both the body and the soul reflects these faith-inspired principles, further illustrating how such values can underpin successful business practices. CarePortal, a nonprofit with a small revenue stream to help fund its work, operates on the belief that faith communities are a vital part of efforts to address issues in the foster care system.

Founder Leisha Pickering explains the values of Musee Bath (3 min):

CarePortal CEO Adren Lewis explains the story and purpose behind CarePortal (3 min):

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Misconceptions about religion, particularly the assumption that faith-based civic engagement is exclusively Christian, pose a challenge to meaningful public dialogue about faith and civic life. The Faith Angle Forum addresses this by broadening the understanding of religious involvement in civic activities. It collaborates with journalists to provide nuanced insights into how various faith traditions contribute to community and national issues, enriching media coverage and informing public perception. Indeed, faith-based civic engagement includes many religions, each offering unique perspectives and motivations for community service and civic involvement, reflecting a rich tapestry of faith-driven activism in America.

Further, contrary to the common misconception that religious schools foster intolerance, a recent meta-analysis reveals that religious education is “strongly associated with positive civic outcomes. The evidence strongly indicates that private schooling correlates with higher levels of political tolerance, knowledge, and skills.” (Shakeel et al., 2024)

To further understand the legal context surrounding religious education and faith-based civic engagement, it’s essential to consider how court cases have shaped the landscape.

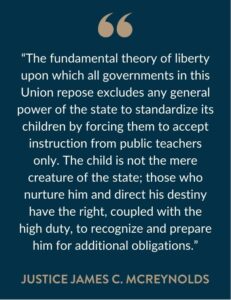

Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925). Strong anti-Catholic sentiment marked America in the early 20th century. During this time, Oregon attempted to shut down parochial schools, requiring parents to send their children to public schools instead. Pierce is a landmark case involving “substantive due process,” the legal principle that some rights are so fundamental that the government cannot regulate them without a compelling reason, even if there’s no explicit constitutional ban on such regulation. The Supreme Court ruled that this law was unconstitutional because it unjustly interfered with parents’ freedom to direct their children’s upbringing and education. In the majority opinion, Justice James C. McReynolds wrote, “The child is not the mere creature of the state.” This case had lasting impacts on the legal landscape regarding education and parental rights, reinforcing the broader principle that certain personal liberties are beyond the reach of state regulation.

Union Gospel Mission of Yakima v. Ferguson. In Washington State, Union Gospel Mission of Yakima is a faith-based non-profit serving people experiencing homelessness by offering shelter, food, recovery, and case management. Recently, the Washington Supreme Court reinterpreted state law to ban such organizations from hiring people who adhere to the organization’s religious beliefs. The mission now faces severe penalties for exercising its constitutional right to maintain such hiring practices. A federal judge in the District Court dismissed the case, but it has been appealed and, as of July 2024, was with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

The legal landscape often requires navigating between religious freedom and government policy. In the case of Chabad of Key West v. FEMA (2020), Chabad of Key West faced challenges in obtaining federal disaster relief funds after Hurricane Irma due to FEMA’s policy that excluded houses of worship from such funding. This policy was contested on the grounds that it discriminated against religious organizations. In response to legal pressure and advocacy by organizations, including the Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty and the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, FEMA revised its policy in 2018 to allow houses of worship to receive aid. This change highlights the importance of nondiscriminatory governmental policies in supporting the integral functions that religious organizations serve within their communities, ensuring their full participation in public and community recovery efforts.

These cases illustrate the dynamic interplay between religious freedoms and legal frameworks, underscoring faith-based civic engagement’s continued relevance and impact in contemporary America.

Addressing the need for reforms in how faith informs public discourse and policy-making, several advocacy groups are actively working to integrate religious insights with civic engagement. Understanding the intricate relationship between faith and civic life is crucial for fostering a more inclusive and engaged society. The following list of organizations demonstrates diverse approaches to bridging the gap between faith-based values and public engagement. Each organization uniquely contributes to enhancing public understanding and promoting constructive dialogue around the role of religion in civic and social contexts. Through educational programs, leadership opportunities, and interfaith cooperation, these initiatives collectively work towards integrating faith into the broader societal framework, enriching civic life, and fostering mutual respect among diverse communities.

- The Center for Christianity and Public Life is committed to interfaith collaboration and mutual understanding across diverse faith communities. Its aim is to deepen religious values’ influence in shaping a more inclusive and thoughtful civic space.

- The “Faithful Political Engagement” video provides guidance on responsibly incorporating faith into political participation.

- Goals of Christian Public Life focuses on articulating and promoting Christian values in public arenas.

- Interfaith America views America’s religious diversity as a foundational strength. It aims to inspire and equip leaders and institutions to foster interfaith cooperation and harness this potential for the common good.

- Interfaith America: A Potluck Nation (5 min)

- The Muslim American Leadership Alliance, led by Zainab Khan, emphasizes the positive impact of Muslim contributions to society.

- SAPIR Journal, featuring Jewish author Bret Stephens, contributes to the discourse on religion’s role in public life.

- The Trinity Forum encourages societal renewal through Christian thought, fostering discussions on faith, arts, and character development.

These efforts collectively aim to deepen religious values’ influence on shaping a more inclusive and thoughtful civic space.

Conclusion

In American history, civic health has fluctuated. Periods of high trust and engagement, such as in the 1830s when Alexis de Tocqueville noted Americans’ propensity to form “associations,” contrast with times like the Gilded Age, marked by low social cohesion. Robert Putnam observed that the 20th century experienced a wave of civic renewal followed by a decline after 1960, continuing to today. In this era of heightened political polarization, relatively low levels of trust, and fraying civic fabric, Americans—even those without a faith tradition—have much to learn from religious communities.

Reinvigorating civic life requires intentional, widespread action, as exemplified by Pastor Josh, who recognized a need in his community and built an institution to address it. In his book, A Time to Build, Yuval Levin identifies a lack of healthy institutions as a critical problem in civil society. Efforts like Pastor Josh’s provide the framework for growing social capital, forming the networks of friendship and coordinated action that characterize healthy societies. By volunteering, connecting with neighbors, and getting more involved in our communities, we can contribute to what Robert Putnam calls the “upswing”—a 21st-century revival of associations and civic health that mirrors the cooperative, interconnected society Americans built in the first half of the 20th century.

What You Can Do/Ways to Get Involved

Use the following list as a starting point to more actively contribute to your community’s growth and well-being.

- If you have a faith tradition, get involved in your place of worship. Consider organizing or signing up for opportunities to serve your faith community or the broader community of your town or city.

- If you do not have a faith tradition, consider exploring nonreligious groups or community-based philosophical organizations. Alain de Botton suggests engaging in community-oriented activities replicating aspects of religious congregations, such as attending lectures or participating in discussion groups focusing on moral and ethical development. These activities help build a sense of community and personal growth similar to that found in religious settings.

- Engage in social activities: Engage in social activities by hosting community dinners, launching a supper club, or participating in local events to build connections. Get to know your neighbors or commit to having colleagues over for dinner more often this year than you did last year. Say “yes” to invitations.

- Attend local government meetings: Stay informed and contribute to community discussion.

- Volunteer: Offer your time through places of worship or values-driven organizations. Examples include, but are not limited to:

- Care Portal to connect with local needs within the child welfare system.

- The Center for Christianity & Public Life to participate in programs that bridge faith and public engagement.

- Repair the World to participate in Jewish volunteer programs focused on social justice.

- Muslim American Leadership Alliance (MALA) to promote individual freedom, cultural understanding, leadership, and Muslim heritage.

- Use online platforms to find volunteering opportunities.

- VolunteerMatch: Discover local volunteering opportunities, including faith-based options.

- Points Of Light Foundation: Find diverse volunteer opportunities and resources.

- Get Involved with advocacy groups:

- Interfaith America: Engage in interfaith cooperation and programs.

- All for Good: A service of Points of Light, All for Good aggregates volunteering opportunities from various sources. Users can search for advocacy-related volunteer opportunities by location or interest area.

- Elect leaders who align with your values: Participate in electoral processes and support candidates whose policies and principles reflect your values and vision for community and societal well-being.

Serve as a civic leader: Integrate your faith or value system into ethical, collaborative, and inclusive leadership roles. Whether through serving on local boards, school committees, or other civic positions, you can influence positive change and embody the principles you value in public service.

Additional Resources

Explore Religious Voting Blocs and Advocacy Groups:

- American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), an influential pro-Israel lobbying group

- The Buddhist Peace Fellowship aligns Buddhist teachings with progressive political issues.

- Catholic Vote is a Catholic advocacy organization promoting issues aligned with Catholic teachings.

- FRC Action, an advocacy arm of the evangelical Christian Family Research Council

- Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty (JCRL) focuses on advocacy without engaging in substantial lobbying or political campaign activities.

- J Street is a Jewish pro-Israel group advocating for peaceful solutions to Middle East conflicts.

- Emgage, an advocacy organization promoting political literacy and civic engagement among Muslim Americans

- Muslim American Leadership Alliance (MALA) fosters community involvement by providing platforms for civic participation, advocating for individual freedom, and promoting dialogue across communities.

- National Latino Evangelical Coalition (NaLEC) advocates for the viewpoints of Latino and Latina evangelical Christians, aiming to offer alternatives to partisan perspectives.

- The Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund promotes civil rights for Sikh Americans.

- SojoAction, Sojourners’ political advocacy arm, is a progressive Christian organization focused on social justice, racial justice, voting rights, and immigration.

More Resources

- Alain de Botton: Religion for Atheists – suggests that non-religious people can gain community-building insights from religious practices.

- The American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) Initiative on Faith and Public Life provides Christian college students opportunities for non-partisan faith-based leadership in the public square.

- The video Politics and the Common Life: A Conversation about Faithful Political Engagement is a one-hour discussion done in partnership with the North Carolina Study Center at UNC.

- The Bill of Rights Institute offers resources on civic virtues and principles.

- The Center for Christianity & Public Life: Explores Christianity’s role in public discourse.

- The Center for Public Justice: Discusses justice in public life.

- Comment Magazine: Guidelines for Supper Clubs where diverse groups can come together for meaningful discussions over shared meals while strengthening community ties. Visit Comment Magazine Suppers for guidelines. Take the initiative and foster dialogue in your neighborhood!

- At supper clubs or other gatherings, consider using the What’s Your Focus? conversation card deck by Authentic Agility Games to foster meaningful discussions based on curated Policy Circle Briefs, provide historical context, and encourage local engagement.

- Faith Angle Forum: This forum enhances journalistic understanding of religion’s influence on American politics and public life through dialogues between journalists and scholars.

- Governor Bill Haslam, in this interview and in his book Faithful Presence, shares insights on integrating faith into leadership and governance.

- Joe Loconte’s essay on Locke and virtue in National Affairs.

- Medium article on Civic Character: Discusses the importance of civic character development influenced by religious and ethical values.

- American Leadership Alliance: Empowers Muslim Americans through storytelling, community engagement, and leadership development programs

- Mustafa Akyol: Writes about and discusses the role of religion and public policy, mainly how to move toward a more pluralistic and democratic Muslim world in modernity.

- Putnam, Bowling Alone at Twenty: Robert Putnam reflects on the themes of the book “Bowling Alone” twenty years later. Also, “Robert Putnam Knows Why You’re Lonely” in the New York Times, a video of the interview, and the podcast version.