POLICY CIRCLE BRIEF

Campaign Finance

Introduction

Campaign spending mainly aims to generate name recognition and reach potential voters with a candidate’s message. Like any enterprise, political campaigns need resources to fund the activities that will help elect the candidate. The amounts vary greatly, depending on the office and whether the race is competitive.

In states deemed “battlegrounds,” spending has reached historic levels, and even school board races have drawn controversy with significant outside donations, although the information in this Brief will be focused on federal regulations.

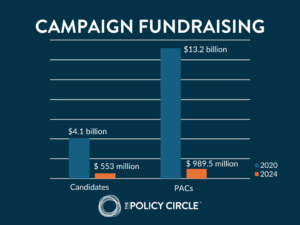

This external financial support and PAC (Political Action Committee) system have led to staggering contributions. For instance, in 2020, the Senate Leadership Fund contributed over $293 million to support Donald Trump, while the Senate Majority PAC contributed over $230 million to support Joe Biden. These were the top two groups for independent expenditures in the 2020 presidential election cycle.

In this Policy Circle Brief, you will learn the basics of campaign finance at the federal level:

- Key terminology and the types of political organizations that raise and spend money to participate in the political process.

- What you need to know before you donate.

- Laws and critical court cases that have shaped how campaign finance exists today.

- Principles of reform and where to find more detailed information and thought leaders.

WHY IT MATTERS

Participating in fair and open elections is one of the many freedoms Americans enjoy. The First Amendment ensures your right to free speech. In addition to voting, you can make your voice heard by contributing directly to a candidate’s campaign or by creating an online video or TV advertisement in support of or in opposition to a candidate. Free speech in the form of support of or opposition to elected officials serves as an important check on the power of the government.

Free and fair elections should maximize people’s ability to run, participate, and support candidates. Critics of setting strict limitations and regulations on campaign financing argue such limitations squelch that participation.

Supporters of campaign finance regulation fear that if funding is unlimited and undisclosed, candidates will be unduly influenced by big donors. They point to corruption and bribery scandals which continue to pop up as recently as July 2024.

Balancing the need for campaign resources, preserving free speech, and ensuring that large donations do not have outsized control is an ongoing challenge.

COMMON TERMS

“HARD” VS. “SOFT” DOLLARS

When an individual donates to support a candidate in a federal election, the donation is allocated differently depending on the organization type and the activities the entity can legally engage in.

“Hard money” refers to contributions that go toward electing candidates and are tightly regulated by the federal government. This type of funding includes donations from individuals— not corporations or labor unions for federal races — to a candidate’s committee, a party committee, or a political action committee (PAC). The fewer restrictions on hard dollars make spending easy, but the strict contribution limits make it more challenging to raise.

“Soft money” (also called non-federal money) refers to contributions to political parties for more general ‘party-building’ activities that the federal government does not regulate. Corporations, unions, and individuals can donate without a limit on the amount. These activities can include vote drives, voter registration campaigns, and ads. Soft money is not allowedto be used in a federal election campaign. Soft money regulation emerged with the passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002 and was amended in the decision on Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE

Political action committees (PACs) are funding sources that are “established and administered by corporations, labor unions, membership organizations or trade associations.” As such, they spend money on elections and can donate money to parties or candidates but are not party-affiliated or an authorized committee of a candidate. The money PACs raise cannot be directed by the political candidates they support. While some of these organizations can give more directly to candidates in certain states, they are much more limited at the federal level.

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) reports on the campaign activity for both political parties and PACs.

SEPARATE SEGREGATED FUNDS

PACs established, administered, or financially supported by a private sector company or labor organization are called separate segregated funds (SSFs). They can only receive contributions from individuals connected to the organization they are associated with, such as those who own corporate shares.

PACs without such a corporate or labor sponsor are called nonconnected PACs. They are financially independent and are allowed to solicit funds from the public.

INDEPENDENT EXPENDITURES ONLY COMMITTEE – A.K.A. “SUPER PAC”

Super PACs exist to make independent expenditures, which cannot be directly affiliated with a political candidate. An independent expenditure is payment for a communication that:

- Unambiguously advocates for the election or defeat of an identified federal candidate.

- It is not organized or created by a candidate, candidate’s committee, party committee, or a candidate’s agents.

Since a super PAC doesn’t coordinate directly with a candidate, the threat of potential corruption should be lower. Quid pro quo corruption typically occurs between groups coordinating unlawful favors.

TAX EXEMPT GROUPS

527 organizations are tax-exempt political fundraising organizations. They are most commonly used as tools for issue advocacy or to drive voter turnout and are prohibited from expressly advocating for the election of a specific candidate. There are no fundraising limits and they must be registered with the IRS and disclose their donors. While these groups are less common, the structure of registering with and abiding by IRS guidelines but not organized as a PAC makes this structure unique among the other political organizations.

501(c) is the IRS’s designation in the tax code for most nonprofit groups. 501(c) organizations account for a small slice of political spending (only 0.83% in 2020 and 0.64% in 2022) but are often involved with policy research and advocacy. They usually inform candidates about policy positions on specific issues.

501(c)(3) organizations are charitable organizations that are “absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign.” This does not exclude voter education programs or activities, but nothing can be tied to a specific candidate.

501(c)(4) groups are social welfare organizations, like volunteer fire stations, and may engage in some political activities as long as they do not favor specific candidates and spending aligns with the mission. If they spend too much on politics, they may be taxed. These organizations are unique because they can engage in political spending but are not required to disclose donors.

501(c)(5) organizations are labor, agricultural, or horticultural organizations and are allowed to lobby and engage in political activity.

501(c)(6) are trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Both operate similarly to 501(c)(4) organizations. The IRS compares the exemptions for the different types of organizations.

What You Should Know Before Contributing

LIMITS ON CONTRIBUTIONS

In a federal general election, an individual can donate a maximum of $3,300 to a candidate or candidate committee. You may contribute as much money as you like to a 501(c) group or a super PAC. There are no limits on independent expenditures or contributions to organizations that pay them.

The 1974 amendment to the Federal Elections Campaign Act of 1971 set the limit for federal elections. Each state has different contribution limits for the election of state and local officeholders.

If you are contributing directly to a candidate, political party, or PAC, there are limits on the amount you can contribute:

- An individual can contribute $3,300 per candidate per election.

- An individual can contribute up to $5,000 per year to a PAC and up to $36,500 per year to a national party committee. These limits do not apply to super PACs or 501 (c) groups.

- State elections: The limit on what you can contribute to candidates and PACs varies by state. There are no limits on contributions to super PACs or 501 (c) groups.

- There are always exceptions. Some states require runoff elections if no candidates secure the majority of the votes. The runoff is considered a separate election, and the donation amount resets. Citizens can donate up to the limit, regardless of the amount they donated in the first election.

In addition to the above regulation and disclosure requirements, federal and state laws prohibit some contributions to political efforts—namely, foreign governments, nationals, banks, and congressional corporations.

DISCLOSING DONORS

Usually, when you donate, you must disclose your name, to whom you donated, your address, your occupation, and your employer. That information is held in public databases at the federal and state levels, where anyone (including journalists) may access it. Campaigns and PACs are required to submit regular finance reports to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and relevant state election offices. If you contribute to a federal candidate, super PAC, PAC, or political party organization (like the RNC/DNC), donations over $200 are disclosed. State laws vary for disclosure.

501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are not required to publicly disclose donor information. As noted above, a 501(c)(3)is precluded from most political activity, and a 501(c)(4) can only spend a portion of its resources as long as it is connected to the mission. 527 organizations are not subject to FEC reporting requirements, but they are subject to IRS reporting.

There is a debate as to whether or not nonprofit organizations should be required to disclose donors on their spending.Some argue the lack of transparency serves special interests and contributes to corruption. Others say disclosure requirements could hurt free expression by discouraging participation and donations. When people give to nonprofit organizations, they do not control what the organization does. People give because they like the aspects of the organization’s mission, but they are not liable for the organization’s every spending decision. Nonprofits must make certain disclosures to the IRS, and in 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that forcing nonprofits to make such disclosures was unconstitutional.

The history of freedom of speech and association in the U.S. is storied, from Common Sense and the Federalist Papers to many major First Amendment cases in the 20th century, such as NAACP v. Alabama. Some donors face the fear that publicizing their political affiliations and contributions could lead to harassment or reprisals, either from government activists or even from fellow parents that they know through their kids’ schools.

WHERE DOES THE MONEY GO?

Campaigns use contributions to pay consulting fees and salaries to political advisors and campaign staff for travel, events, supplies/equipment, research/polling, and office space. One of the most significant expenses is ads. The political advertising machine is extensive, from those who direct the strategy to those who make the ads and others who purchase airtime in the target media markets.

This report predicts that the 2024 presidential campaigns will spend over $12 billion on political advertisements, with the majority going towards television marketing fees. Direct mail is another prolific form of political advertising you probably receive in your mailbox around campaign time, particularly for local campaigns.

WHO DONATES?

Individuals who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents can donate to political campaigns, subject to contribution limits. Corporations and labor unions cannot donate directly to federal campaigns but can contribute to super PACs. Foreign nationals and federal government contractors are prohibited from contributing to federal elections.

Overall, very few people donate to political campaigns. Surveys have found that fewer people plan on donating in 2024 than in 2020. Further, the survey estimates that two-thirds of Americans have never donated to a campaign.

Once an individual has raised or spent more than $5,000, they must register with the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) as a candidate and transfer funds into a campaign account with disclosure requirements.

Individuals are not the only ones contributing to political campaigns. Political groups, nonprofits, and charities majorly support political candidates. The FEC provides easy-to-navigate definitions for other election-related organizations that fund campaigns.

The Role of Government

FEDERAL

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) oversees federal elections. This independent regulatory agency administers and enforces federal campaign finance law, meaning it has jurisdiction over House, Senate, presidential, and vice presidential campaign finances. The FEC is made up of six commissioners who are selected by the president and confirmed by the Senate. There cannot be more than three members with the same political party affiliation, and there has to be a majority for a motion to pass.

Federal campaign finance law focuses on the public financing of presidential campaigns, the public disclosure of fundscontributed to federal political candidates and limits on such contributions and expenditures.

STATE

States can set their campaign finance laws, which must comply with federal law. These state laws are set in the state constitution, adopted into law through legislation, or created through ballot measures, while others borrow from the federal government’s guidelines.

States must also comply with federal Supreme Court and lower court decisions from their circuit or state. Federal and appeals court precedent applies to all elections, but states can create laws outside those rulings.

All states have a governing body for campaigns that oversees state and local elections, either through a State Board of Elections, its office of the Secretary of State, an ethics commission, or another campaign finance-type regulatory body. The National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL) has broken down campaign finance laws and contribution limits. Ballotpedia compares campaign finance laws across the states.

LEGISLATION

Financing campaigns is nothing new and has become increasingly complex. The first restriction on soliciting campaign contributions was the 1867 Naval Appropriations Bill, which prohibited government officials from asking naval workers for money.

In the early 1900s, concerns about the influence of corporations prompted the passage of the Tillman Act in 1907. After the act was established, Congress passed several more pieces of legislation, including the 1910 Federal Corrupt Practice Act, the 1939 Hatch Act, and the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, establishing campaign finance limitations, regulations, and disclosure requirements.

The multiple laws proved difficult to enforce since there was no single framework. Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 to replace the existing patchwork laws. This act resulted in a set of disclosure requirements from candidates and parties and created the framework for PACs. Congress amended the Act in 1974 to set more limitations on spending and contributions and to establish the Federal Election Commission, an independent agency to oversee campaign finance.

By the 1990s, there were calls for the Act to be reformed. Congress enacted the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (also called the McCain-Feingold Act) in 2002 to address issue advocacy and soft money.

BIPARTISAN CAMPAIGN REFORM ACT OF 2002

This legislation was passed to increase trust and transparency in financing elections. However, a common critique of this legislation is that the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) has not fulfilled its intentions of shoring up confidence in the political system and reducing the role of big money in elections.

Advocates for the law hoped to preserve the integrity of elections and the process. By regulating soft money donations, it was thought there would be less chance for corruption and that faith in the system would increase. Large contributions would be publicly known, which should increase accountability.

The BCRA ended the practice of large donations by individuals and corporations to official national political party committees, which have highly regulated disclosure rules. Instead, donors directed that money to outside groups with less stringent disclosure rules, reducing the public’s ability to scrutinize the donations. Thus, the treasuries of party organizations like the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Republican National Committee (RNC) have shrunk because donations have increasingly gone to outside groups who have set up 501(c)(4)s and super PACs for political activity. Likewise, the influence of party organizations has decreased.

THE SUPREME COURT AND SIGNIFICANT COURT CASES

The First Amendment ensures your right to free speech, which extends to your right to contribute directly to a candidate’s campaign or make public statements supporting or opposing a candidate. The Supreme Court has generally supported this right, and they are broadly considered an anti-corruption tool.

However, there are limits, and the Supreme Court has worked to balance concerns about corruption without infringing too broadly on First Amendment rights.

MAJOR CAMPAIGN FINANCE SUPREME COURT CASES

Buckley v. Valeo (1976)

The Watergate scandal led to the conclusion that the Federal Elections Campaign Act of 1974 was too broad, prompting Congress to pass amendments in 1974. Two years later, in Buckley v. Valeo, the court stepped in and ruled on what you can and cannot do with campaign donations. The Supreme Court ruled that spending limits on campaigns violated the First Amendment, but donation limits did not. Limits on campaign contributions were also thought to preserve election integrity. Limits on what the campaign could spend, though, hampered their ability to compete and became a restriction on the freedom of speech for donors and candidates.

“[T]he concept that government may restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.”

BUCKLEY V. VALEO DECISION

The Court let stand a federal $1,000 candidate contribution limit per individual donor, per election (counting the primary and general elections separately). However, the Supreme Court overturned contribution limits set so low that they impeded free speech and association.

Randall v. Sorrell (2006)

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on June 26, 2006, that Vermont’s campaign finance laws, which imposed limits on contributions and expenditures for non-federal elections, were unconstitutional. The Court found that the expenditure limits were not substantially different from those previously deemed unconstitutional in Buckley v. Valeo and that Vermont’s justification for these limits was insufficient. Additionally, the Court held that the contribution limits were so low that they violated the First Amendment by preventing candidates from amassing necessary resources for effective advocacy. The ruling emphasized that these limits were not narrowly tailored “to prevent corruption,” and thus, the imposed limits were deemed excessive burdens on First Amendment interests.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010)

This ruling addressed the constitutionality of restrictions on corporate funding of independent political broadcasts in candidate elections. The case arose when Citizens United, a nonprofit organization, sought to air a film critical of Hillary Clinton and challenged the FEC regulations that prohibited corporate-funded electioneering communications. The Court found that the restrictions on corporate expenditures were not justified by the government’s interest in preventing corruption or protecting dissenting shareholders.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. FEC fundamentally changed the landscape of campaign finance. The Court argued that media expenditures do not lead to corruption or the appearance of corruption and that the First Amendment protects political speech regardless of the speaker’s corporate identity. Additionally, the Court upheld the constitutionality of disclaimer and disclosure requirements for electioneering communications, asserting that these requirements do not impose a ceiling on campaign activities or prevent anyone from speaking.

The ruling has significantly impacted the political and electoral process in the United States. By allowing corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on political advocacy, the decision has increased their influence in elections, potentially overshadowing individual contributions and altering the dynamics of political campaigns. This shift has sparked ongoing debates about the balance between free speech and the need to prevent undue influence in the democratic process.

In 2018, Khan Academy explained the overall structure of campaign finances and talked about the impact of the Citizens United case after it went into effect, all of which remains accurate today (9 min):

McCutcheon v FEC (2014)

In the case of McCutcheon v. FEC, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that aggregate limits on the total amount an individual could contribute over a two-year period to all federal candidates, parties, and political action committees (PACs) were unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The Court’s 5-4 decision, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, emphasized that while the First Amendment protects the right to participate in democracy through political contributions, it is not absolute. The Court concluded that the aggregate limits did not effectively prevent corruption or its appearance, which was the only legitimate governmental interest recognized in Buckley v. Valeo (1976). Instead, these limits were found to unjustifiably restrict a citizen’s ability to engage in fundamental First Amendment activities.

By removing the aggregate limits, the ruling allowed individuals to contribute to as many candidates, parties, and PACs as they wished, provided they adhered to the base limits for individual contributions. Critics argued that this could increase wealthy donors’ political influence, potentially undermining the democratic process. However, the Court maintained that only direct quid pro quo corruption—where contributions are made in exchange for specific official actions—could be regulated and that broader concerns about influence and access did not justify the aggregate limits.

Principles of Reform

In 2023, a Pew Study found that 72% of Americans believe that campaign spending should be limited. Most Americans reported they believe major political donors have too much influence and the people they represent do not have enough. At the same time, a large majority think campaigns cost so much that it prevents good candidates from running. All of this suggests that Americans do not think that the current campaign finance system is effective.

There is a delicate balance between election integrity, preventing corruption, and campaign solvency. Candidates’ funding sources need to be disclosed to maintain transparency and public trust. The thought behind this recognizes that citizens should know of any major financial influences on the candidates since they will influence their actions. Creating too many barriers can discourage donations and make it difficult to fundraise and be successful.

For campaigns to proceed, they need to raise enough money to be competitive, get their message out to a broad audience, and win. Future reforms need to balance eliminating bias with First Amendment rights.

Conclusion

It is up to you to choose how and to whom you donate. Donating is a personal decision that can make a difference by making yourself heard. It’s also prudent to know the laws if you are donating so you know the information that will be disclosed. Knowing the limits is essential to ensure you comply, especially if you are running.

Reviewing financial reports for candidates, which are available online through your state election office and the FEC, can also be informative as you evaluate candidates to learn more about the support each has garnered.

How you engage in the policy discussion is important too. The key questions at the heart of historic legislation and court cases remain today:

- What are the appropriate limits on donations to candidates and their PACs?

- Should limits on donations or spending apply to so-called super PACs?

- What level of disclosure of contributions is appropriate?

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about campaign finance.

- Do you know how campaigns are financed in your community or state?

- What are your state’s campaign finance laws?

- Is there a coalition/task force/organization/project on citizen funding in your community?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of coalitions, boards, or committees in your state?

- What steps have your state’s/community’s elected/appointed officials taken?

Reach Out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is an excellent opportunity to develop relationships with people outside your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Find allies in your community in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state. Talk to your friends and colleagues.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team at [email protected] for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Search for articles about candidates that interest you.

- Research what groups are supporting each of the candidates. It might encourage you to donate to a political organization supporting your cause instead of directly to the candidate or to contribute to a candidate and a philosophically aligned organization.

- Candidates and organizations make it very easy to donate. Click the “Donate now” button on their homepage, where you will also see the fine print of how the funds can be legally deployed.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Additional Resources

- Institute for Free Speech

- Federal Election Commission, its legal resources, and its candidate and committee guides

- National Conference of State Legislature’s Election Resources

- Ballotpedia’s Federal Campaign Finance Laws and Regulations and State Laws Map

- Campaign Legal Center’s Campaign Finance Resources

- The Congressional Research Service reports on campaign finance laws in Congress.

Newest Policy Circle Briefs

The First-Time Voter Handbook

Assessing Candidates Guide

Women and Economic Freedom

About the policy Circle

The Policy Circle is a nonpartisan, national 501(c)(3) that informs, equips, and connects women to be more impactful citizens.