Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

Between 2014 and 2016, two coal mining companies closed in Delta County, Colorado, resulting is the loss of 1,000 jobs in the rural community of 31,000 residents. Even before this blow, the county had been experiencing significant population decrease as more people left to find work elsewhere. A lack of high-speed Internet access prevented new businesses from getting off the ground, and pushed many others to leave.

In 2015, the local economic development agency Region 10 received a grant from the Colorado Department of Local Affairs for a broadband implementation plan for the county. Region 10 partnered with Delta-Montrose Electric Association, a local electric cooperative that connects fiber to members’ homes. Then, locally-owned and operated Lightworks Fiber & Consulting won a contract with the electric association to build the network. Lightworks even hired and trained former coal miners to lay the fiber-optic cable. As of 2019, 80% of Lightworks employees were former coal workers.

The coordinated effort at the local level succeeded in bringing high-speed Internet access to the county, attracting more people to the community to live and work.

Why it Matters

The digital landscape considers the spaces and networks created by technological developments and digital infrastructure, as well as the role of stakeholders in these areas. Digital infrastructure refers to the infrastructure that is needed to maintain and operate a national and international computer network, process e-commerce transactions, and create, distribute, and access digital media content online. This digital infrastructure allowed the Internet’s public implementation over twenty years ago. The Internet has since driven innovation that has contributed to economic and social prosperity around the world.

We depend on digital infrastructure when we search for directions, look up the answer to a question, or talk with loved ones overseas. We might not even realize how important it is to issues of national security, and the education and health of folks from rural America to Tanzania. Especially in light of the coronavirus pandemic, digital infrastructures “is being recognized as essential infrastructure for building resilient communities that can respond effectively to a public health emergency.”

Putting it in Context

History

By the early 1900s, visionaries such as Nikola Tesla had imagined a worldwide wireless system. The idea became a reality in the 1960s when MIT’s JCR Licklider joined the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Licklider started working with packet switching, a new method of transmitting electronic data by breaking files into small chunks, or “packets.” With packet switching, researchers connected an MIT computer in Massachusetts to one in Santa Monica in 1965. This was the first step in creating the first Internet prototype, ARPANET, a network that allowed computers to communicate on a single platform.

In 1973, Robert Kahn and Vinton Cerf from the Defense Department developed the first standards for transmitting data, called the Transmission Control Protocol and Internet Protocol (TCP/IP), and enabled the creation of a vast “network of networks.” This led to Telenet, the first commercial version of ARPANET and the first Internet Service Provider (ISP).

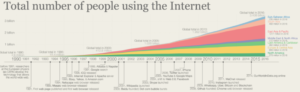

In 1983, Paul Mockapetris from UC-Irvine created the Domain Name System (DNS) for categorizing websites. We know this system by website endings, such as -.edu, -.gov, -.org, and -.com. Then in 1990, Tim Berners-Lee at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) developed HyperText Markup Language (HTML). After this, the World Wide Web (WWW) was born and today is still the most common way to access data online through websites and hyperlinks. The WWW officially entered the public domain in 1993. It has since seen the creation of companies that profit from organizing information on the web, such as Google’s search engine (1998), Facebook’s social network (2004), YouTube (2005), and Twitter (2006).

Key Terms

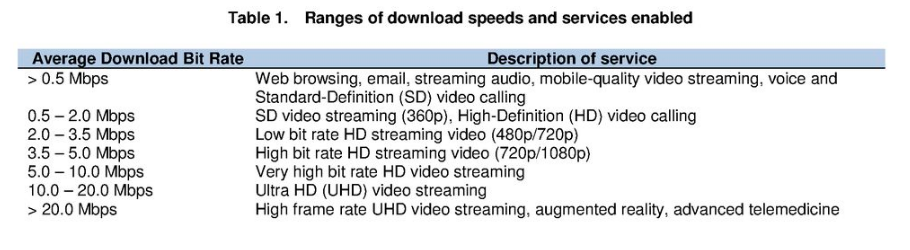

Today, access to the Internet mainly relies on broadband, which is constant high-speed Internet access that is faster than accessing the Internet through telephone lines or dial up. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the United States authority on telecommunications and information services, defines broadband as “Internet connection with a download speed of 25 Megabits per second (Mbps) and an upload speed of 3 Mbps.”

There are two main types of broadband. Mobile Broadband is designed for constant, on-the-go use; fixed broadband is designed more for stationary use in homes or businesses. Examples of broadband services are satellite, cable, DSL, and fiber. Broadband service from satellites is often impacted by line-of-sight problems, and cable broadband services are provided by TV cable companies. DSL, or Digital Subscriber Line, is delivered by a mix of traditional copper phone lines and fiber. Fiber, as in fiber optics, is the use of glass fibers to carry data; although faster than copper, fiber requires new infrastructure that is expensive to install.

Fiber contributes to new technology generations, abbreviated to G. There is a 1G and a 2G, but 3G was the first informally-set standard for wireless technology, and is understood as basic Web browsing, email, and video and picture downloading. 4G provides these services at a faster rate, and LTE, Long Term Evolution, is the latest and fastest of the 4G technology. Recently, technology companies have started advertising 5G services. 5G focuses on advanced technologies and the “Internet of Things,” such as artificial intelligence and the interconnectivity of devices – like Amazon’s Alexa, but on a grander scale. 5G is still mostly in the development stages, but is already becoming “a bone of contention” since it will require new many new physical components to tech systems, such as new towers, utility poles, and buildings – “most cities want 5G, but they don’t want to be told how, when and at what cost.”

CNBC breaks down 5g (6 min):

For a better understanding of 5G, check out this download speed simulation.

Experts predicted 2020 would be the year “5G went mainstream,” and even though demand picked up as people tried to stay connected during the COVID-19 pandemic, speeds were slightly underwhelming. As coverage gets better, speeds get faster, and 5G-enabled phones become less expensive, demand for 5G will likely increase. As of the end of 2020, there were over 200 million 5G subscriptions worldwide; telecommunications company Ericsson predicts this will reach 2.8 billion by 2025.

By the Numbers

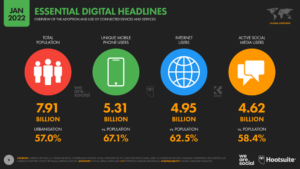

In 2016, Our World in Data estimated that almost 3.5 billion people had access to the Internet. In January 2022, Datareportal estimated close to 5 billion people, 62.5% of the world’s population, were using the Internet.

The global distribution of Internet users, however, is unequal. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), only 20% of people are Internet users in the least developed countries, compared to 80% of people in developed countries. This is mainly do to slow download speeds and high price tags, as roughly 2.3 billion people around the world live in countries where even a 1-GB mobile broadband plan is unaffordable for someone earning an average income.

This makes it difficult for citizens of these nations to participate in the digital economy. The Bureau of Economic Analysis calls the digital economy the “contribution of high-tech goods and services, international trade, digital-enabling infrastructure, e-commerce transactions and digital media” to GDP. According to the UNCTAD, global exports of information and communication technologies (ICT) services grew annually by 7-8% between 2005 and 2017. In 2017, ICT services were worth $2.7 trillion. In 2020, worldwide retail e-commerce sales grew by 16.5% to just under $4 trillion as customers turned to ordering online during the coronavirus pandemic. In the U.S., where total e-commerce sales for 2019 reached $595.5 billion, e-commerce sales for the first three quarters of 2020 totaled $581.5 billion, and are anticipated to grow 16% to reach $1 trillion in 2022.

The Role of Government

Digital infrastructure is a shared service that benefits all users by growing the economy and improving quality of life. In the U.S., government was involved during the development of the Internet prototype, ARPANET, and the TCP/IP, which still serves as an Internet standard. The government has also helped establish the role of the private sector in the digital world. Today, the Department of Commerce maintains that around the world, “governments, working in concert with other stakeholders, must create a legal, policy, and diplomatic environment conducive to creativity, competition, and investment.”

Governments can influence the digital landscape by:

- Generating policies that remove regulatory barriers to support competition

- Developing strategies for resource management to finance access and innovation

- Enacting reforms to promote an open internet while also protecting privacy

Such reforms usually involve making digital infrastructure more affordable, providing incentives for public institutions, businesses, or individuals to adopt technologies, and advancing social and economic goals, although methods differ across countries. Australia and France, for example, have digital infrastructure investment programs that use government funds. In the United States, there is more emphasis on performance standards and policies that encourage private sector involvement and competition. The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, and the General Services Administration are largely involved in producing information technology legislation and policies.

Federal

U.S. government activity in the digital landscape has focused on cybersecurity, data protection, Net Neutrality, and access to broadband (more on these areas below). There is also debate around removing regulatory barriers to enable deployment of existing technologies and clear the way for newer technologies. Other contested issues include competition and antitrust enforcement when it comes to large technology companies, and strategies for unused or underutilized government held spectrum, particularly in the race to 5G.

Governing Commissions

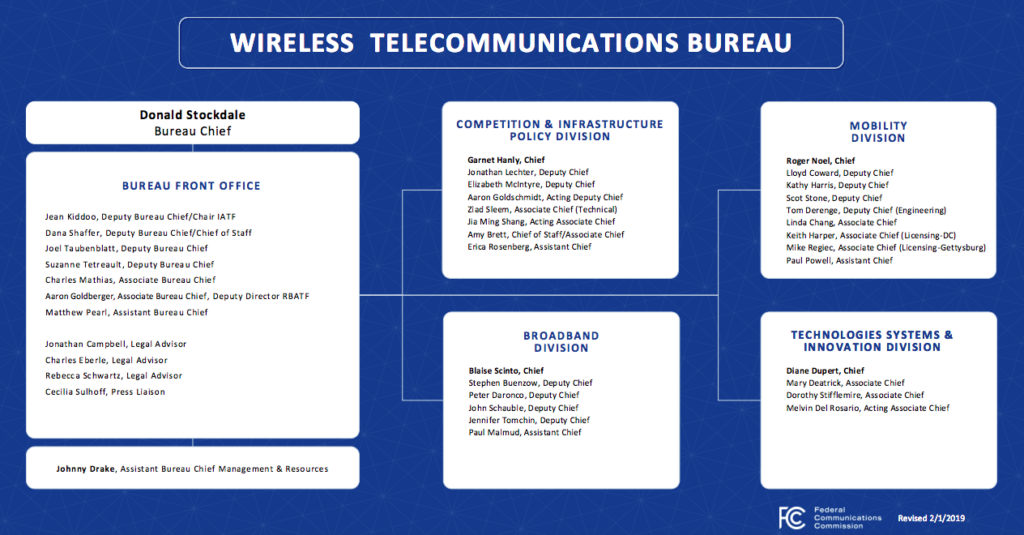

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), an independent government agency that is overseen by Congress, serves as the “primary authority for communications law, regulation and technological innovation.” The president appoints and the Senate confirms five commissioners to direct the FCC, and the president selects one to serve as chairman. The FCC is organized into a number of bureaus and offices that develop regulatory programs, encourage innovation and investment, conduct investigations, oversee homeland security, and manage public safety.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), an independent government agency that is overseen by Congress, serves as the “primary authority for communications law, regulation and technological innovation.” The president appoints and the Senate confirms five commissioners to direct the FCC, and the president selects one to serve as chairman. The FCC is organized into a number of bureaus and offices that develop regulatory programs, encourage innovation and investment, conduct investigations, oversee homeland security, and manage public safety.

The FCC itself also has its critics; the commission and its vast and complicated web of policies have been labelled “opaque and prone to failure.” Additionally, the charge to uphold “the public interest” is broad, and critics say this ambiguity protects the FCC from legal responsibility.

Besides the FCC, the main body that handles public policy and challenges in the digital landscape is the Internet Policy Task Force (IPTF), which includes an array of experts from Department of Commerce agencies, including the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the International Trade Administration (ITA). Additionally, the Department of Commerce sets the domestic and international digital agenda, which includes:

- Ensuring a free and open internet by supporting a a multi-stakeholder model to foster a consensus-driven policy-making process. One example is the 2015 UN review of initiatives from the 2003 and 2005 World Summits on the Information Society. The meeting created the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) to promote best practices for exchanging information.

- Providing consumer data protections, which resulted in the 2012 Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights that requires privacy notices for consumers. International efforts include the Privacy Shield to protect data flows between the United States, the European Union, and Switzerland, and the Cross Border Privacy Rules, a similar measure with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

- Promoting innovation and updating standards, such as protecting intellectual property rights and access to data. The TM5 USPTO is a forum that promotes cooperation among five of the world’s largest trademark offices, and handles half of worldwide trademark applications. Projects to make data more accessible include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Big Data Program. The project creates an open platform for the private sector and academia to access NOAA data, and has formed successful partnerships in areas such as renewable energy and navigation.

- Focusing on users, such as through BroadbandUSA, which provides technical assistance to local, state, and federal institutions as well as private organizations and academia. The focus is specifically on senior citizens, low-income Americans, and Americans living in rural areas, for whom availability, cost, and technological skill level are barriers to Internet access.

Regulations and Legislation

The Telecommunications Act

A key question as Internet services were developed was whether they were telecommunications or information services. In 1996 the FCC under the Clinton Administration passed the Telecommunications Act. The act established a clear distinction between telecommunications services (telephone systems) and information services (at the time, private data systems). This was important because Title II of the Act subjected telecommunications services to FCC regulation, but did not regulate information services the same way. Then-FCC Chairman Bill Kennard claimed the goal was to keep the Internet as unregulated as possible. The act resulted in an incredible boom in cable broadband investment and competition.

Technological advancements soon caused the convergence of the broadband and telephone markets. By the end of the 1990s, consumers demanded telephone companies offer data services, but this was difficult under the 1996 Act. Consumer demands also led to new questions about how to categorize broadband: If a telephone company provided Internet, was it an information or telecommunications service? In 2002, then-FCC Chairman Michael Powell ruled that Internet access provided by cable companies (such as Verizon and AT&T) was an information service and not a telecommunications service, meaning it would no longer be under FCC regulation. The ruling accounted for new innovations in broadband and created a new market for plenty of investment by telecommunications companies, cable companies, and wireless providers.

Given the extent of new competition, the FCC presented the Internet Policy Statement to guide management of network traffic in 2005. In 2010, this became the Open Internet Order, which prohibited Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from discriminating against content providers. Verizon sued the FCC in response, claiming the FCC did not have the authority to regulate ISPs based on Title II. In January of 2014, the Court sided with Verizon and started the debate around Net Neutrality. Net Neutrality is covered in more detail below.

The Communications Decency Act

Title V of the Telecommunications Act, the Communications Decency Act, includes “one of the most valuable tools for protecting freedom of expression and innovation on the Internet: Section 230.” Section 230 says that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” This means that providers are not legally accountable for content published on their platforms; people can upload videos to YouTube and or leave reviews on Amazon without either company being sued for the content. There are exceptions for criminal claims, but in general Section 230 has “let online speech and commerce flourish without the constant threat of frivolous lawsuits looming overhead.”

State

The federal government has broad powers to finance public investments, which means federal grants can support digital equity programs coordinated by states, local governments, and tribes. One example is the grant that allowed Colorado’s Delta County to coordinate its broadband expansion.

Additionally, more than twenty states have dedicated broadband offices to address broadband access amongst their constituents, and more have task forces, working groups, and committees within other agencies. These groups bring together a variety of stakeholders, such as Minnesota’s Governor’s Task Force on Broadband that has 15 members representing “communities, businesses, local governments, educational institutions, health care facilities, tribes, and ISPs.”

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Expanding Broadband Access

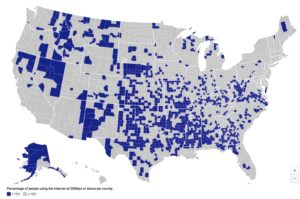

The FCC’s Broadband Deployment Report estimates fewer than 20 million Americans lack broadband Internet access. However, “that number is based on flawed data from internet-service providers.” Internet service providers self-report these numbers, but if they offer services to at least one household in a census block, the FCC counts the entire census block as covered. BroadbandNow Research estimates in reality as many as 42 million Americans actually lack access. The Verge used data from Microsoft to estimate the broadband service people are receiving nationwide:

If government officials do not have “a clear picture of where service gaps exist…parts of the country will be left out when it is time to distribute funds.” Additionally, having disconnected sectors of the population “undermines policy objectives in areas such as health and education, as well as broader economic and social development” since private and public services require reliable broadband.

Digital equity means making “affordable High-Performance Broadband available to low-income, unserved, and underserved populations…accompanied by training in digital skills that empowers users to make the most of their connections.” High-performance is another key component of this; the FCC has not updated its definition of broadband since it was originally set, which means the current standard “constitutes inadequate service for households that are sending simultaneous video stream to support distance learning, teleworking, and other needs such as remote health care.” Updating these standards is necessary, because these are the standards that grant recipients must reach; if they do not support today’s necessary Internet functions, it will result in federal dollars being spent on “‘a broadband network that’s become obsolete in the time it took to build.’”

Back in 2017, a Brookings Institution report found that “digital skills have now become a prerequisite for basic economic inclusion,” because even if jobs themselves have limited digital components, many job applications are exclusively available online. The coronavirus pandemic has illustrated the lack of digital equity; remote work has been concentrated mainly to high-income earners in urban and suburban areas.

The Wall Street Journal explains why many rural Americans still lack broadband access (7 min):

Rural America is not alone; access issues also affect those in urban areas. For example, Melissa Morrone, a supervising librarian in Brooklyn, has seen many people gathering outside the doors to try to catch the library’s wifi; many people can’t afford broadband, even if they have access to it in the city. Regardless of location, roughly 40% of Americans who make less than $30,000 a year lack home broadband connections or a computer.

The federal government provided $22 billion between 2015 and 2020 to specifically support the expansion of rural broadband. Additional resources from coronavirus rescue funds can be put towards broadband development, and the American Jobs Plan signed into law in November 2021 provides $65 billion in spending for broadband. In the spring of 2022, 20 internet service providers agreed to increase speeds or cut prices so eligible U.S. households can receive free high speed internet through federal programs. The FCC estimates the cost to deliver broadband to all Americans currently lacking it amounts to roughly $80 billion, although this may be a low estimate if the FCC data on the number of Americans lacking broadband is also low.

Leveraging federal resources already budgeted can help with this. Lifeline, the $9.25-a-month program initiated by the Reagan administration to ensure everyone could access 911, could be revamped and put towards Internet expansion, “but the funding is largely limited to telephone companies” for the time being. Additionally, expanding broadband has the potential to boost economic growth: Broadband construction is estimated to create at least 20 direct jobs per million dollars spent, and these jobs usually pay over 40% more than average for manufacturing jobs in the U.S.

Competition

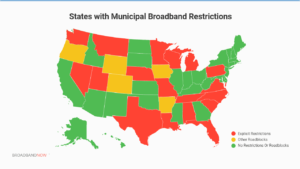

At the state and local level, there are 18 states that have “substantive roadblocks to establishing municipal networks to residents,” including regulations that prevent municipalities from offering broadband services to residents. The goal is to prevent government from crowding out the private sector, and take care with government spending; government-backed entities depend on taxpayer dollars, and one such project in Utah found itself $350 million in debt over 9 years. But other reports have found that compared to states with these restrictions, states without these restrictions “enjoyed higher access to low-priced broadband plans on average.” For example, some of these limitations have left rural communities with expensive, older services with poor reliability, slow speeds, and an inability to pursue another option. At typical broadband speeds, almost 80% of Americans only have one or two service providers to choose from.

Lowering barriers to entry, incentivizing new investment through grants, and encouraging public-private partnerships can encourage small providers (such as rural electric cooperatives or investor-owned utilities) to bring broadband to homes that commercial broadband providers do not reach.

Local Communities Get It Done

There have been a number of local initiatives to find the best solutions for individual communities, based on the needs and resources of the state and localities. What works in California, where there are a few national and regional providers will likely not be the solution in Minnesota where many residents depend on small local companies and providers, or in Tennessee where rural electric cooperatives are expanding into broadband.

Working with the private sector is another option. Washington state developed “one of the nation’s earliest nonprofit, open-access, middle-mile networks, owned and controlled by several Public Utility Districts representing communities across the state, to encourage rural localities and private broadband providers to connect remote residents.” In January of 2015, New York’s Broadband Program Office began its own public/private partnership program to more quickly develop broadband services in underserved areas. The program provides state grant funding for projects proposed by Internet service providers. The state has formed partnerships with 34 companies. Vermont partnered with Microsoft and local service providers to provide public Wi-Fi hotspots to underserved areas towns in response to gaps highlighted by COVID-19. Arizona is partnering with Cisco to expand broadband access to high-need communities in the state.

Discover how other communities are investing in their own Internet infrastructure.

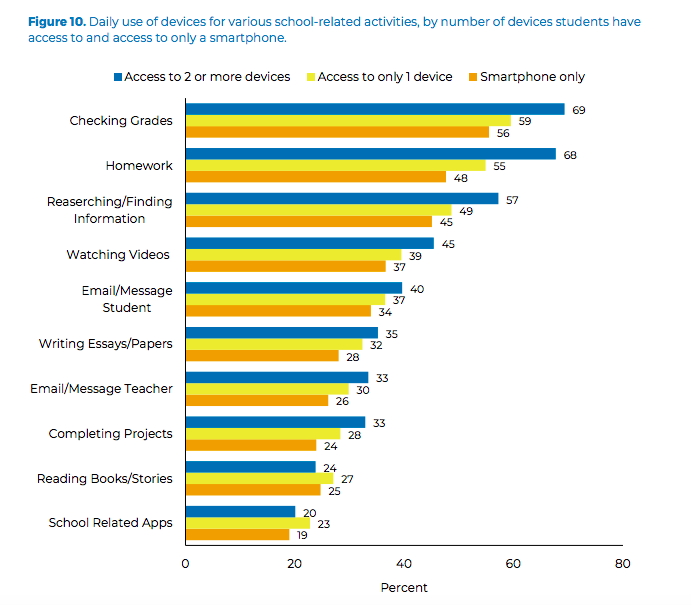

Increasing Broadband to Support Education

Gaps in broadband connectivity can have negative effects on other social and economic sectors, including education. In higher education, online classes and “self-paced e-learning” were already globally generating almost $43 billion annually by 2013. Technology was regularly used in the classroom, and students were frequently assigned work that required Internet use well before the coronavirus pandemic closed schools and forced many Americans to rely on home broadband services. However, there are many who lack access to broadband’s educational benefits. The “homework gap,” the gap between households with school-age children that have knowledge of and access to broadband and those who do not, is a barrier not only to learning but also to participating in broader online communities and the digital economy.

According to researchers at the Quello Center at Michigan State University, differences between students with limited or no home internet access and those who do have access is “equivalent to the gap in digital skills between eighth- and eleventh-graders.

In the U.S., the FCC’s E-Rate Program provides funding for Internet access in schools and libraries, although this is limited to the physical buildings. The circumstances of the coronavirus pandemic have prompted petitions to redirect some of the E-Rate funds to extend broadband access, using these community anchor institutions as “launching pads for community-wide access.”

Utilizing Digital Infrastructure to Improve Healthcare

The healthcare industry faces difficulties upgrading to new technologies due to the complexity of medical systems and the massive amounts of data hospitals generate. For healthcare providers, interoperability presents the greatest challenge. The “interoperability hurdle” refers to “the capacity of health information systems to work together within and across organizational boundaries.” There is no single place where physicians can go to find patient data, and Stanford found that fewer than one-third of hospitals can electronically “find, send, receive, and integrate patient information from another provider” – most hospitals still fax paperwork. However, once different hospitals and healthcare systems start sharing data, it may become unclear which parties own which data sets, and data breaches in healthcare tend to cost more than any other industry due to HIPAA fines and lawsuits.

Federal resources have mostly gone to encouraging new technologies. The FDA Digital Health Innovation Action Plan loosens regulations to provide patients and providers with access to “high-quality, safe and effective digital health products,” such as mobile apps that track data or display medical imaging. This has fostered collaborative projects such as the Apple Heart Study, which recruited 400,000 participants to test Apple Watch technology that could detect atrial fibrillation. Between 2013 and 2017 Alphabet, Microsoft, and Apple together filed over 300 health care patents for such wearable technologies. Uber and Lyft have also entered healthcare to provide patients with rides to and from doctor appointments.

On the other hand, complex state and federal regulations have stifled telehealth. Telehealth and telemedicine refer to the use of Internet and communication technologies to support long-distance clinical health care. Digital infrastructure is critical for telemedicine, as connectivity allows physicians in city centers to train physicians or communicate with patients in rural or remote locations. This eliminates geographical and financial barriers while ensuring timely treatment for patients who are unable to travel long distances, but only for those who have the broadband access and digital skills necessary.

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, many of the regulations were altered to make telehealth easier. More than half of physicians reported they were using telehealth to treat patients during the pandemic, compared to only 18% of physicians in 2018. However, Dr. Eric Wallace of the University of Alabama at Birmingham says affordability, lack of technology, and lack of digital literacy among patients is just as much of an issue as broadband access. Of the 200,000 telehealth visits the university has conducted over the course of the pandemic, 40% were audio instead of video because of these reasons.

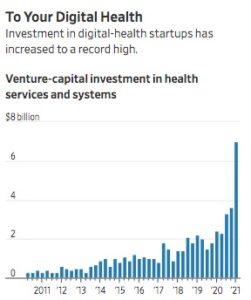

Entrepreneurs have seized the opportunity presented by telehealth; digital-health startups have boomed since the start of the pandemic, with record amounts of capital flowing in. The WSJ explains, “In the age of smartphones and low-cost sensors, digital-health startups promise that they can deliver cheaper, more effective and more convenient healthcare.”Corporate-benefits executives are excited about the potential to lower costs and improve employee health, but are still finding services redundant and overpriced. Employers say digital-health providers would need to integrate with insurers to be most effective, and whether these new providers do lower costs and improve care is still being determined.

Entrepreneurs have seized the opportunity presented by telehealth; digital-health startups have boomed since the start of the pandemic, with record amounts of capital flowing in. The WSJ explains, “In the age of smartphones and low-cost sensors, digital-health startups promise that they can deliver cheaper, more effective and more convenient healthcare.”Corporate-benefits executives are excited about the potential to lower costs and improve employee health, but are still finding services redundant and overpriced. Employers say digital-health providers would need to integrate with insurers to be most effective, and whether these new providers do lower costs and improve care is still being determined.

Protecting Open Internet and Data Privacy

The progress of technology in the last twenty years has resulted in incredible innovation, much of which have occurred because online platforms have enjoyed protections such as those provided by Section 230. Section 230 protects internet service providers and online platforms “from liability for the decisions they make about the content they host,” meaning they cannot be held liable (in most cases) for what third parties post. While Section 230 enabled platforms the freedom to grow and innovate, it has not gone unopposed. Some argue that Section 230 provides too much immunity for providers; for example, in terms of child safety, the law could prevent “parents from bringing a claim of negligence against [a social networking site] for failing to protect the safety of its users.” Additionally, as political rhetoric has become more contentious online, the fact that Section 230 does not require political neutrality has prompted debate for a Fairness Doctrine that would limit Section 230 protections to platforms that “operate in a fair and balance manner.” Many fear government action on Section 230 would upend web-related activity, and argue that such management violates freedom of speech. For more on Section 230 and the debate on free speech, see The Policy Circle’s Free Speech brief.

Bloomberg explains how Section 230 came about, why lawmakers want to change it, and what this could look like (7 min):

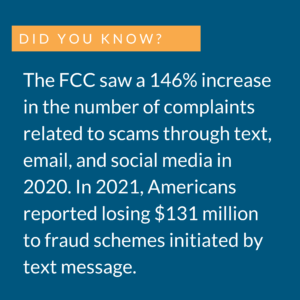

Another reason for technological progress and advancements is that government data is open. Still, data breaches (see Cambridge Analytica, Facebook, and Marriott) and fraudulent websites have sparked concerns about a completely open Internet. Even World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee has spoken in favor of governments protecting consumers and their privacy. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is in charge of protecting consumers’ privacy and security in the United States, but federal legislators acknowledge that many laws put “the burden on individuals” and that responsibility should shift to “companies to handle data fairly.”

At the state level, California has passed its own Consumer Privacy Act, which focuses on consumers’ right to dictate how their data can be used. Nevada and Maine have followed suit, passing their own personal data protection laws. A number of states including New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Oregon, and Texas have also passed data breach notification laws. For more on data privacy, see The Policy Circle’s Data Privacy and Cyber Security brief.

Net Neutrality

Government oversight of the Internet usually brings up net neutrality, which refers to the “concept that all Internet traffic should be treated equally.” This means Internet Service Providers (ISPs) cannot privilege their own content or slow down their competitors’ content. For example, an ISP such as Comcast is not allowed to slow video streaming services from Netflix or Amazon because they compete with a Comcast cable plan. Net neutrality reflects tension between service providers, who want to process and serve data to consumers quickly, and content creators, who want everyone everywhere to see their content.

After receiving a large amount of public support for Net Neutrality, the FCC voted to pass the Open Internet Order in February 2015. This reclassified broadband as a telecommunications service and, based on Title II of the 1996 Communications Act, brought broadband services under FCC regulation. In December 2017, a proposal passed that repealed the Open Internet Order, reclassifying broadband as an information service, ending FCC regulation, and overturning earlier net neutrality requirements. Some states responded by introducing their own net neutrality legislation.

Net neutrality supporters fear that ISPs may charge content providers for privileged access to their networks, which will result in higher costs for consumers. These “Internet fast lanes” could favor established companies that have the funding to pay. Others argue service agreements between ISPs and customers should protect against this, and say the Federal Trade Commission could handle any anti-competitive behavior by ISPs. Critics of net neutrality also maintain that unnecessary regulations could increase costs and decrease the quality of services provided. The debate is ongoing, and it remains unclear what the FCC’s authority over the Internet should look like.

Competing Internationally

How does the US compare with the rest of the world when it comes to digital infrastructure? The United States ranked 3rd worldwide on the World Intellectual Property Organization’s 2021 Global Innovation Index. The US remains first in research and development investment spending, and is just behind China in total number of patents. Successful international developments include the NIST’s Smart Grid Interoperability Framework and the Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards. The frameworks are the primary references for power grid interoperability standards in the United States, Japan, Korea, China, and the European Union.

In 2020, the U.S. ranked just outside of the top ten countries with the fastest broadband speed. China and the U.S. are in a kind of race to establish a functioning 5G network. This has mounted tensions between the U.S. and China, particularly regarding Huawei (pronounced wah-wey), one of the world’s top smartphone makers and leaders in telecommunications infrastructure. Citing national security concerns, U.S. government agencies are banned from using technology sold by Huawei.

Enhancing Cybersecurity Measures

As the race to build a 5G network continues, it has become clear that whichever country dominates the system will control its information flow and “will gain an economic, intelligence, and military edge.” This understanding has raised concerns about cyberattacks, which have doubled since 2015.

In April 20201, the U.S. intelligence community released its annual global threat assessment, which also points to cyber threats from Russia, China, and North Korea. Addressing cyberthreats while keeping the Internet open and reliable is the challenge, and focuses include working with partner nations to develop and share best practices, such as the Convention on Cybercrime of the Council of Europe, the “only binding international instrument” on cybersecurity. Within the federal government, reforms include increased cross-agency cooperation. The public sector must also work with academia and civil society to maintain an educated workforce aware of cyberthreats and foster collaboration with the private sector to protect the technology marketplace. The Center for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue University takes this one step further; established over the summer of 2021, the center is the first independent think tank at the intersection of technology and U.S. foreign policy.

Conclusion

As the global digital infrastructure continues to develop and the global digital economy continues to grow, it will be necessary for public and private stakeholders, from governments and international organizations to businesses and individual users, to collaborate and ensure the safety, reliability, and equal distribution of digital advancements.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about digital infrastructure.

- Do you know the state of broadband access in your community?

- What are your state’s laws in regards to net neutrality?

- Does your state have a broadband initiative, or a task force?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of initiatives or task forces in your state?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed official taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, libraries, and local businesses – everyone is affected by broadband access

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- See if your state has any regulations on broadband development.

- Explore examples of how communities are investing in their own Internet infrastructure, and if you can apply this to your own community.

- See if your area is eligible for the USDA’s ReConnect Program for rural Development.

- Harvard Business School’s Digital Initiative, Duke Digital Initiative, and MIT’s Initiative on the Digital Economy are some examples of universities exploring emerging technologies. See what initiatives or research your alma mater or state universities are involved in.

- Consider how well your data is protected. The website haveibeenpwned.com will tell you whether your email has been compromised via a hack, so you can take steps to fix it.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

Other associations include:

- The State Science and Technology Institute is a national nonprofit organization that offers services, information, and support for technology innovation.

- Women in Technology advances women in technology by providing support, leadership development, education, and networking and mentoring opportunities around the Washington, D.C./Maryland/Virginia metro region.

- NPower, operating in New York, New Jersey, Texas, California, Maryland, and Missouri, aims to empower a digital workforce, specifically young adults from underserved communities and military veterans

- Opportunity Education is a United States-based foundation that seeks to improve primary and secondary education around the world by using technology and digital learning to empower students and teachers.

- The HP Catalyst Initiative is a global project that has support from academia and international organizations such as the Carnegie Corporation, the Consortium for School Networking, and the National Science Resources Center. The initiative has a number programs based out of universities around the world.

- The international non-profit organization Health Level Seven (HL7) sets standards in over 50 countries for sharing electronic health information

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Digital Landscape? Consider exploring the following: