Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

The number of U.S. workers voluntarily leaving their jobs started in the spring of 2021 and hit an all-time high in the second half of the year. In November, 4.5 million U.S. workers quit their jobs. Between May and September 2021, U.S. workers left 20 million jobs, an increase of 50% during the same period in 2020 and 15% higher than in 2019. Some deem this “higher-than-normal quit rate” as the Great Resignation.

In August of 2022, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released a report stating 4.2 million people, or 2.7% of the workforce, quit their jobs in July 2022. This is a slight decline in the trend but has remained between 2.7% and 2.9% since July 2021.

From March to June 2021, the quit rate stood at 2.5% across all industries and increased to 2.8-3% from September to December 2021, compared to 2% or less during the same periods in 2020. The numbers are even higher in specific industries, particularly, experts note, where work is in-person and relatively low-paying. In June, the highest resignation rates were in accommodation and food services (5.7%) and leisure and hospitality (5.3%). These industries have the highest job openings (10.2% and 10.1%, respectively).

There are 11.2 million job openings currently, but the percentage and number of working-age adults in the labor force are well below pre-pandemic levels. The labor force participation rate (people who are either working or actively looking for work) was 62.4 % in August 2022, up from the pandemic decline but still below the February 2020 rate of 63.3%. Some experts point out that the pandemic pushed many individuals with the ability to retire early. Still, this decrease also amounts to 1.4 million fewer adults ages 25 to 54 working or looking for a job.

Many experts assumed school reopenings would allow working mothers to return to work or that the expiration of expanded unemployment benefits would push others back to work. Neither had a noticeable impact on the labor market. The slow return of prime-age workers may directly affect how quickly the economy recovers and grows, impacting wage growth and inflation over the coming months.

Why it Matters

Work has long been a critical component in the formula for Americans’ pursuit of happiness, one of the promises outlined in the Declaration of Independence. This article from Positive Psychology indicates work satisfaction and well-being come from pursuing two work-related goals: earned success (a sense of accomplishment and professional efficacy) and service to others (the sense that your job makes the world better).

Several studies support this claim, including a link between unemployment levels and suicide-rate increases. Another study found a 1% increase in the unemployment rate lowers population well-being by more than five times as much as a 1% increase in the inflation rate.

But the nature of work is changing. Increased technological innovations, including work-from-home software, and the extended impact of the COVID-19 pandemic led many Americans to reconsider their ideal employment situation. This working-to-live mentality came to the forefront of the labor market, unlike in preceding decades. This perspective change increased small and micro businesses, especially among black Americans and women.

However, negative impacts affect many Americans, especially those with the least amount of education and economic attainment. The gap between the number of job openings and those qualified to fill them has widened, which threatens the economy’s continued growth and denies people the opportunity to experience their own earned success.

Putting it in Context

In correspondence dating back to 1786, founding fathers James Madison and James Monroe alluded to the importance of people fulfilling their physical needs and moral and emotional dimensions. Texas A&M political scientist James R. Rogers points out that public discourse about happiness, even then, “meant prosperity or, perhaps better, well-being in the broader sense.”

By the Numbers

Labor Force Participation

As outlined in The Policy Circle’s Economic Growth brief, the labor force participation rate measures the working-age (16-64) population of the economy – the percentage of the people either working or actively looking for work. As of August 2022, the labor force participation rate stood at about 62.4%, marking the first time since February 2020 that the rate rose above 62%.

The U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in July 2022 that the number of job openings in March stood at 11.2 million and the number of hires at 6.4 million. Approximately 4.2 million separated from their jobs (quits, layoffs, and discharges).

As of August 2022, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the total number of individuals not in the labor force stood at 9.92 million based on data from the Current Population Survey. This includes 9.4 million who do not want a job, such as retirees, and 570,000 discouraged by job prospects. Before the pandemic, there were more unemployed people than jobs; in February 2022, there were about 1.8 jobs per unemployed person.

Unemployment

After spiking to just under 15% at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in April 2020, the unemployment rate fell to about 3.7% as of August 2022, closer to historical averages. Notably, a low labor force participation rate can paint a misleading picture of unemployment. The unemployment rate excludes people who want a job but are not actively looking for work. People who search for work are not included in the unemployment rate, making it seem lower than the actual number of unemployed individuals. Microbusiness owners are considered” self-employed” and included in unemployment rates, skewing overall rates.

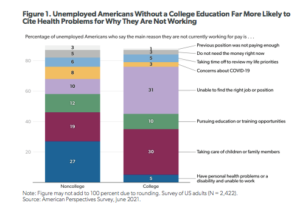

Data from the American Enterprise Institute found the characteristics of unemployed people have changed since the coronavirus pandemic. Since its start, the unemployed tend to be younger, lower-income, and with lower education backgrounds than the general population. They are out of work for an average of 20 weeks, up from 9 weeks before the pandemic. In January 2020, only 20% of unemployed individuals were without jobs for more than six months. In late 2021, that stood at 80% of the unemployed population.

Obstacles to returning to work vary among the public. For example, one in three women not currently working say caring for children and other family members is the main reason not to pursue employment. This figure rises to 42% among women ages 30-49. Alternatively, only 8% of men cite family responsibilities as a reason not to pursue employment and note personal health conditions, education opportunities, and the inability to find the right job.

Few Americans (12%) report they work multiple jobs, but about 25% say they do something to earn extra money outside their household’s primary source of income. This is especially true among those with part-time jobs (38%), those who are unemployed (38%), and retirees (20%), although nearly three-quarters of those with side hustles say they do not want that work as a full-time occupation.

Unions

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 7 million public and 7 million private sector employees were members of unions in 2021. In total, 10.3% of wage and salary workers were members of unions, a decline from 10.8% in 2020. The highest unionization rates were in education, training, and library occupations (34.6%) and protective service occupations (such as police officers and firefighters, 33.3%). The lowest unionization rates were in farming, fishing, and forestry occupations (4%), sales occupations (3%), and food preparation and service occupations (3.1%).

The Role of Government

Federal

The government plays a role in the labor market in a few key areas. The Department of Labor enforces and administers more than 180 federal laws that cover workplace activities for roughly 150 million workers.

The most recent labor and industry bill, passed by the Biden Administration on August 9, 2022, is the CHIPS and Science Act. This bill specifically addresses America’s future workforce with domestic technology manufacturing and heavily invests in STEM, sciences and technology “from K-12 to community colleges, undergraduate and graduate education.” Partnering with the private sector to invest in these industries bolsters American jobs, positions America to compete in the global technology market, diminishes reliance on Chinese manufacturing, and further enhances national security.

Minimum Wage

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a minimum wage, the legal floor below which employers cannot pay their workers, overtime pay, recordkeeping, and youth employment.

Health and Safety

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 requires employers to comply with workplace health and safety standards. The Act created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration under the Department of Labor to set and enforce measures to ensure safe working conditions and provide training, outreach, and education. Federal law mandates that firms purchase insurance that pays certain benefits to workers injured on the job.

Unemployment Insurance

Under the Department of Labor, unemployment insurance programs “provide unemployment benefits to eligible workers who become unemployed through no fault of their own and meet certain other eligibility requirements.” Unemployment insurance is a joint state-federal program; each state administers its program but follows the same federal guidelines.

Unions

Federal labor laws influence union membership and establish rules for collective bargaining. In the 1930s, legislation encouraged union growth. Before this, workers were often required to sign contracts prohibiting them from joining unions. Clashes between striking workers and employers often involved strikebreakers and government intervention. In particular, the Wagner Act of 1935 guaranteed unions the right to self-organize (without employer interference) and the right to bargain as a unit with employers. The bill created the National Labor Relations Board, an independent federal agency that “[safeguards] employees’ rights to organize and to determine whether to have unions as their bargaining representative.”

Career and Technical Education

The Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 was the first federal funding authorization for vocational education, also referred to as career and technical education. Congress reauthorized the act as the Carl D. Perkins Act of 1984 and again reauthorized it in 1990, 1998, 2006, and 2018. The bill allocates nearly $1.3 billion annually for career and technical education.

Congress

The following Congressional committees are most influential on the labor market:

- The House Committee on Education and Labor has jurisdiction over education and workforce programs from preschool through high school, higher education, and continuing education. This includes initiatives under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WOIA).

- WOIA, signed into law in 2014, requires states to align workforce development programs with the coordinated needs of job seekers and employers. It aims to help job seekers access employment, education, training, and support services and to match employers with needed skilled workers.

The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions has jurisdiction over areas including equal employment opportunity, labor standards, labor disputes, occupational safety and health, wages and hours, and pensions and retirement plans.

State

States are in charge of several administrative labor market tasks, including complying with implementing federal legislation. For example, each state establishes a minimum wage law within the parameters of federal legislation. See each state’s minimum wage here. Similarly, each state has an office for occupational safety and health. Find out about your state’s occupational health and safety plan.

Further, each state administers an unemployment insurance program. See a list of state labor market information contacts here and compensation officials here. Explore different unemployment benefit policies by state, or find those for your state here. You can also find how accurately your state pays unemployment insurance here.

Licensing

One area of the labor market in which states are uniquely involved is occupational licensing. The states set licensing rules and cover occupations from plumbers to massage therapists. Each state makes its own rules, which means it is up to the states to maintain high public health and safety standards while also ensuring licensing policies that do not inhibit economic growth or workforce mobility. At a more local level, states are best equipped to understand the needs and challenges of the local labor market.

Since each state has different licensing requirements, people who work in industries that require licensure need to meet their new state’s requirements to work in their field of employment.

The Role of the Private Sector

The private sector comprises privately-owned, for-profit businesses (i.e., those not owned or operated by the government). The private sector relies on paid employees and plays a crucial role in developing the workforce it needs to succeed.

Worker education and training, for example, is an area many in the private sector have championed. Merit America offers technical training and professional development with dedicated coaches and peers. Jobs for the Future and Corporation for a Skilled Workforce work to coordinate the American workforce and education systems to increase economic mobility.

At the Aspen Institute, the Economic Opportunities Program and the Future of Work Initiative specifically look to build economic stability and empower workers by focusing on the ever-changing occupational landscape, harnessing emerging technologies, and reimagining workplace protections.

Challenges & Areas for Reform

COVID Changes

The pandemic altered many employees’ work arrangement preferences, unemployment experiences, and career aspirations in the workplace. This prompted what experts call “The Great Resignation,” emphasizing “the higher-than-normal quit rate of American workers” that began in the spring of 2021 and continued into 2022.

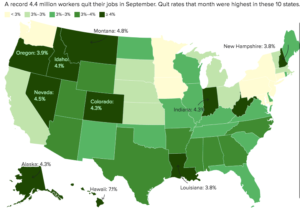

About 4 in 10 U.S. workers reported they considered leaving their job, which is relatively consistent with historical trends. The variation comes through demographics and occupations; for example, 7% of all workers in Hawaii quit in September 2021, more than double the national quit rate of 3% and the highest in the country. The Wall Street Journal reports that surveys show “low-wage workers, employees of color, and women outside the management ranks are those most likely to change roles.” In the leisure, hospitality, construction, and manufacturing industries quit rates are at record highs. Plentiful job openings, increased household savings, and a child-care crisis made the possibilities of changes more attractive for some workers.

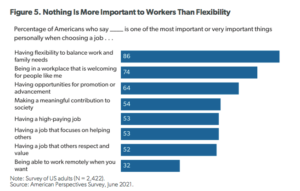

Brent Orrell of the American Enterprise Institute explains, “The unemployed are looking for work. However, they are not necessarily looking for the same jobs they had a year ago.” The millions of available jobs are not always the jobs people want. Shelly Steward, director of the Future of Work Initiative at the Aspen Institute, explains that most low-paying jobs don’t have benefits, schedule flexibility, or stability.

Further testament to the desire for flexibility is the increased number of self-employed workers. Self-employment increased by 6% since the start of the pandemic, while overall U.S. employment remains 3% lower than at the beginning of 2020. The number of unincorporated self-employed workers has risen by 500,000 since the start of the pandemic to 9.44 million, the highest since 2008.

From January to October 2021, 4.54 million new businesses registered with the IRS, up 56% from the same period in 2019 and the most significant number since 2004. Of those, two-thirds were not expecting to hire any other employees. The Brookings Institute reports technology and marketing innovations made online businesses more accessible to people looking for alternative income streams.

One popular example is Etsy, an online marketplace where individuals can make, sell, and buy items from clothing to jewelry to unique home goods. The website had 7.5 million active sellers as of September 2021, up from 2.6 million in September 2019. Internal surveys show that 4 in 10 sellers started on Etsy for reasons related to the pandemic.

Technology

Technology has substantially impacted almost every aspect of life, from how cars helped create suburban sprawls to the social effects of companies like Twitter and Facebook. The workplace is no different.

Telework

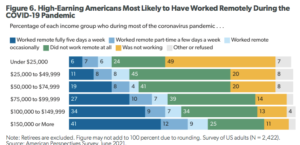

For some workers, flexibility during the coronavirus pandemic came in the form of telework, but it was not widespread across the workforce. Before the pandemic, less than 10% of the U.S. workforce worked remotely. In March 2020, that percentage jumped to 35%. As of late 2021, it hovered around 14%. The percentage is skewed, however, as illustrated by the chart below. The frequency of remote work increases with education and income.

Early in the pandemic, over half of employers reported productivity gains thanks to remote work compared to before the pandemic. Others were able to cut costs for office space. Remote work allows companies to take advantage of broader applicant pools. Workers also see benefits; remote work offers more six-figure jobs than any individual U.S. city. At the same time, remote work alters the culture, social interaction, and collaboration of companies and organizations.

Economist Dr. Adam Ozimek extensively researched U.S. Remote Workers in a Global Economy, comparing data for pay and opportunities. Dr. Ozimek concludes industries like sales and marketing can earn U.S. remote workers premium pay and widespread opportunities in the global marketplace. Further, U.S. remote workers offer foreign companies greater assistance to navigate the U.S. legal system and consumer markets, and, ultimately, provide increased opportunities for collaboration.

Automation

Concern surrounding smart machines, artificial intelligence, and robots replacing existing human jobs is genuine. Machines handled about 30% of tasks in 2021, and humans did the rest, but that balance is expected to shift to 50/50 by 2025.

Some argue automation will create new, different jobs that will decrease the need for physical labor and make workplaces safer for humans. Pricewaterhouse Coopers’ Global Artificial Intelligence Study estimates jobs lost to automation will likely be offset by creating new jobs. According to World Economic Forum estimates, by 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced but offset by 97 million new jobs across 26 countries.

Another argument in favor of automation is that workers in low-skilled jobs will be displaced and unable to find a job in the new workplace environment, potentially increasing the digital divide and exacerbating inequalities. Research from MIT economists found that from 1990 to 2007, each additional robot added in manufacturing replaced an average of 3.3 workers nationally, and lowered wages by almost 0.5%. Reskilling and upskilling will likely be necessary; the World Economic Forum predicts that 50% of all employees will need reskilling by 2025.

Kevin Roose, author of Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation, argues that automated intelligence and other technologies have incredible potential and limits; technology may dominate in some industries but not others. For example, four manufacturing industries (automakers, electronics, plastics, chemical, and metal manufacturers) account for 70% of robots. Additionally, technology is not “a disembodied natural force that simply happens to us, like gravity or thermodynamics.’” Humans, not robots, make decisions about the use of emerging technologies.

Occupational Licensing

Occupational licensing is designed to protect consumers and ensure only capable individuals hold specifically skilled positions. In the 1950s, only 5% of occupations required licensure. Since 2020, 25-30% of full-time employees, amounting to about 30 million U.S. workers, have jobs that require licensure.

Licensure establishes a professional standard to ensure the safety and health of the consumers, but some argue that licensing creates barriers for young and low-income workers. Individuals must meet specific education requirements and pay the required fees to receive a license. This can take a long time which, for some, means foregoing paychecks. Adding to the burden is the cost of education and training programs. For example, to become a licensed hair braider in Louisiana requires 500 hours of training.

The Biden administration announced in July 2021 an executive order that included measures to streamline licensing requirements. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) would ban unnecessary licensing restrictions that restrict economic mobility; which specific occupations will be addressed is up to the FTC. Still, state bodies set licensing rules, which complicates endeavors for national changes. See this report, from the National Conference of State Legislatures, for state licensing profiles (starting on page 24).

Interstate compacts “afford states the ability to address many of the challenges associated with state-level licensing through flexible, state-developed collaboration and without federal preemption.” For example, the Nurse Licensure Compact allows nurses who hold a license in one state to practice in another state that participates in the compact.

Apprenticeships allow individuals to “work alongside mentors and gain hands-on experience,” which can help individuals meet education or training requirements mandated by licensing boards. Those in pursuit of licensure would benefit from earning wages during an apprenticeship.

A Toyota plant in Kentucky launched an apprenticeship program to address the local skills gap. The program has since expanded to 33 chapters in 13 states through the Manufacturing Institute’s effort to scale the program nationwide. The Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education (FAME) provides workforce development through 2-year apprenticeship-style programs in advanced manufacturing. The program builds strong mentor-mentee relationships between students, instructors, and employers. Employers subsidize trainees’ costs as an incentive to ensure the students succeed; 85% of graduates are reportedly hired by their employers for the program.

Career Pathways

Younger Workers

First jobs can substantially impact employment prospects later on in a person’s life. According to the Aspen Institute, “Research has shown that youth unemployment can have lasting consequences – repressed wages decreased upward mobility, and lessened productivity over a person’s work life.” Young people today are up against several obstacles in the search for gainful employment.

Fewer Entry-level Jobs

According to the Federal Reserve, the percentage of graduates who hold “good non-college jobs” (positions with a full-time average annual salary of $45,000 or more) has been declining for the past two decades. Among recent graduates, 35% are employed in good non-college jobs, and 40% are in positions where a degree is unnecessary.

Inadequate Preparation

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation noted that new hires are often “unsure of how to write a professional email,” or “struggle to organize and prioritize tasks.” Only half of managers believe recent graduates are adequately prepared for the workforce.

“Soft” skills include communication, critical thinking, team orientation, diligence, and integrity. Data from the Graduate Management Admission Council reports most industries, companies, and graduate school recruiters want people who demonstrate communication and teamwork skills, followed by technical, leadership, and managerial skills.

According to economist Harry J. Holzer, soft skills significantly impact educational attainment and future earnings. In schools, soft skills are hard to define and, therefore, hard to incorporate into the curriculum, particularly when teachers have other education targets mandated at the local, state, or federal levels. Partnerships between businesses and the education sector could close the soft skills gap, as no one knows better the skills employers need than the employers themselves.

For example, the Nike School Innovation Fund focuses on partnerships with public schools in Oregon, where a large portion of Nike’s workforce resides. The program pairs Nike leaders with ten high school-based teams. College MAP (Mentoring for Access and Persistence) from EY (Ernst & Young) and the nonprofit College for Every Student is a mentorship program that connects over one thousand employees with underserved youth annually. Job Corps is another program through which young adults can learn skills to communicate effectively with supervisors and coworkers. The American Dream Academy (TADA), in collaboration with the Milken Center and Coursera, created a three-year program meant to provide skills training and career mobility opportunities for underemployed Americans.

Older Workers

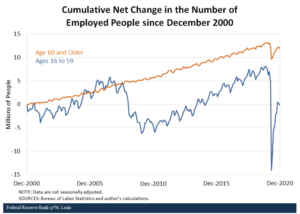

Many in our more experienced population of workers are enjoying retirement. Many others continue to work, either because they want to or need to because of financial necessity. Total U.S. employment grew by 8.5% from 2000 to 2020 due to increased employment of people aged 60 or older.

Many people under the official retirement age left the workforce ahead of schedule due to the pandemic. An estimated 2.6 million Americans retired earlier than expected between February 2020 and October 2021. Some are considering reentering the workforce. Labor shortages and the widespread availability of remote work is appealing, and others “realized they were not as financially prepared to live without a steady paycheck as they hoped.” The Policy Circle’s Financial Literacy Brief takes a closer look at the state of retirement finances among Americans.

These more experienced workforce members can be invaluable sources of information for younger generations. It is worth exploring how society can pull from mentors and tap into that knowledge capital from the aging population to inspire the younger generation. What action can we take to remain connected and create opportunities for the older generations to share their know-how with others, innovate, and spark something new? The Policy Circle’s Aging in the 21st Century brief explores this topic further.

Distressed Communities

Distressed communities in our country encompass urban centers, rural communities, and former industrial hot spots. These communities typically experience lower workforce participation levels.

The Opportunity Zone initiative is part of the 2017 tax reform bill and is meant to drive opportunity into these communities. The effort charged the governors of each state to list up to 25% of their census tracts that meet “distressed community” specifications as an opportunity zone. The “low-income census tracts are places with an individual poverty rate of at least 20 percent and median family income no greater than 80 percent of the area median.”

Mobility Mentoring provides workforce readiness and economic mobility coaching programs in the private sector. A Brandeis University evaluation of the 2009-2015 pilot program found participants increased their earnings by 72%, and 90% of participants received new postsecondary credentials. The combined gains in wages and taxes, coupled with reductions in public subsidies, exceeded program costs by $8,000 per participant per year. The program targeted individuals in transitional housing for homeless families and stabilization and supported housing for previously homeless families.

The success led to the development of the Economic Mobility Exchange, a learning network designed to share and improve the Mobility Mentoring approach with other organizations. In 2020, almost 150 organizations in 37 states participated, from community colleges, housing organizations, and foundations to health care institutions, child-serving agencies, and state and municipal agencies.

Those exiting the prison system represent a labor source who may face challenges finding employment, which is critical to avoid recidivism. Before the pandemic, the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people was 27%. However, a more recent estimate from the Prison Policy Initiative based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data released in early 2022 places the number as high as 60%.

The First Step Act, signed into law in December 2018, includes the reauthorization of the Second Chance Act’s “transitional jobs strategy” meant to provide activities “that promote skill development, remove barriers to employment,” and provide “job retention, re-employment services, and continuing and vocational education.”

In the private sector, programs such as Hope for Prisoners offer mentoring and skills training for ex-offenders that help prepare them for employment. According to a University of Nevada, Las Vegas study of 522 program graduates, 64% found stable employment. Of those employed, 25% found a job within 17 days of the training course, and only 6% of graduates were re-incarcerated during the 18-month study period. Employment opportunities exist as well: Greyston Bakery in New York practices open hiring, meaning there are no background checks; Café Momentum in Dallas reaches at-risk youth at their culinary training facility, which provides life skills, education, and employment opportunities; Down North Pizza in Philadelphia, started and ran by formerly incarcerated individuals, pays wages starting at $15 per hour, offers space in two apartments above the restaurant to avoid housing discrimination, and connects staff with legal representation.

Reskilling and Vocational Training

According to the National Skills Coalition, only 43% of workers in the U.S. are adequately trained for middle-skill level jobs, despite comprising 53% of the labor market.

Reskilling involves “equipping workers with the tools and education needed for a new job.” This can be within the same company (upskilling) or re-educating lower-skill employees to fill the widening middle-skill work gap outside their current company (out-skilling). Many companies find it difficult to justify the cost of training employees to leave. For others, “it has good optics for brand reputation and generating goodwill with departing employees,” explains Lori Freifeld, editor-in-chief of Training Magazine. “It’s counter-intuitive, but by helping a worker be prepared to leave, you’re more likely to get them to stay longer and achieve more.” Additionally, reskilling ventures tend to cost significantly less than traditional degree programs a company sponsors employees.

Conclusion

Not everyone sees employment opportunities in the same light. Take Uber, for example. Some believe that part-time jobs like driving for Uber or Lyft trap people in a job that does not provide health insurance. Others look at Uber, and the sharing economy, in the context of leveraging assets, breaking down regulations, and opening up opportunities. This example shows labor market opportunities, and the wants and needs of employees and employers vary. Exploring innovative ways to create career pathways for both sides of the market is the key to self-sufficiency and earned success, which all contribute to a thriving economy.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about creating career pathways.

- Do you know the state of the labor market in your state or municipality?

- What are your area’s local unemployment statistics?

- What is your state’s labor force participation rate?

- What are your state’s laws?

- What occupational licensing laws does your state have?

- What unemployment policies exist in your state?

- How accurately does your state pay unemployment insurance?

- Are there workforce development programs in your state?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the labor market information contacts in your state?

- Who is in charge of worker compensation in your state?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected or appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is an excellent opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts in your preferred fields.

- Find allies in your community or nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, faith-based organizations, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team at communications@thepolicycircle.org for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Attend a local school board meeting and voice the needs of businesses in the area

- Work with local schools to identify skills and jobs needs

- Set up a career exploration day for students to visit local businesses or businesses to come to a school

- Explore internship matching opportunities

- Reach out to education nonprofits or mentoring programs to offer your services

- Identify a school or district to open a dialogue

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Innovative Solutions and Perspectives

Allison Grealis – President, Women in Manufacturing

Allison Grealis – President, Women in Manufacturing

Allison presented at the 2018 Policy Circle Summit. She discussed the role of associations, using the example of the manufacturing industry where women make up a much lighter proportion of the field than other industries. In such an environment, the need for women to empower other women stands out. Allison provided tips on how to connect and build a network, and also how to empower others to enter into the field to grow and change it for the better.

Read Allison’s bio here.

Antonio Ortiz – President, Cristo Rey Jesuit High School

Antonio Ortiz – President, Cristo Rey Jesuit High School

The Cristo Rey Network seeks “to transform urban America and break the cycle of poverty one student at a time.” Antonio spoke at the 2018 Policy Circle Summit about the importance of first jobs for high school students that lead to careers. In this model, companies create opportunities for a real job experience with real work. Here’s a snapshot of the innovative solution and best practices Antonio shared: Companies pay around $36,000 to have a high school student work in a full time job. The job is carried out by 4 students: a Freshman, Sophomore, Junior, and Senior. Each works at the job one day a week and they alternate on Mondays. In return, each student earns $9,000. Tuition to attend Cristo Rey is $12,000. Through this structure, students gain real world work experience that helps them step into a job that is a pathway to a career when they graduate, and the (mostly low income) students earn the income they need to be able to afford a quality education.

Read Antonio’s bio here.

Krissy DeAlejandro – Executive Director, tnAchieves

Krissy DeAlejandro – Executive Director, tnAchieves

The mission of Tennessee Achieves, or tnAchieves, “is to increase higher education opportunities for Tennessee high school students by providing last-dollar scholarships with mentor guidance.” What this generally looks like is a full ride technical scholarship to colleges that guarantee job placement after graduation. Through the program, a student ends up paying a percentage of their salary towards tuition so they have “skin in the game” and stay on track with the classes and skills that will lead to a job. This also motivates the colleges to offer courses that will lead to a career.

Colorado is another state that has implemented innovate private-public partnerships to connect youth to career opportunities.

Read Krissy’s bio here.

Mario Kratsch

Vice President, German American Chamber of Commerce (GACC) Midwest

Germany pioneered the apprenticeship program. Mario is passionate about creating career pathways for American workers. To accomplish this, Mario helps lead a German / American apprenticeship program. In this model, companies create a job in an apprenticeship form and then hire employees that they pay to train. The company partners with a community college to provide a certification that is recognized by an industry. Currently over 70 U.S.-based companies collaborate to provide skill development training and certification programs for very technical jobs to make this model a success. The mindset is one of building a workforce with technical skills who aren’t full-fledged engineers. The challenge is this: ensuring more technical colleges are working hand-in-hand with industry. And in working together, they can make sure each program builds a skill-set marketable beyond one company. What can we learn from this German model? How do we make sure our state-level Education Boards partner with industry to define standards and create programs that not only meet demand, but also create careers?

Read Mario’s bio here.

Mark Feinour – Executive Director of the Support Services group at Bank of America.

Mark Feinour – Executive Director of the Support Services group at Bank of America.

Bank of America is leading the way in celebrating intellectual disabilities as a gift, as a way to say: “Define us by our actions. Cherish us for our personalities. Reward us for our accomplishments.” The Bank of America Support Services division is an in-house marketing and fulfillment operation with 300 employees that has been employing individuals with intellectual disabilities for over 25 years.

While government programs exist for employing workers with disabilities, Bank of America is not taking tax credits for these positions have the same entry level salary ($15 an hour) and benefits as any other employee at Bank of America. Each of us can use those lenses to look at the work we do – is there a way for me to create a job for someone with a different ability? Mark’s playbook is helping other organizations do it. This type of initiative needs a champion who wants to make it a priority. It started with one person at Bank of America. The Chairman of Bank of America’s board decided to create a job for his neighbor with down syndrome whose family worried about his future as a productive member of the community. It started with just a few employees.

Read Mark’s bio here.

Strada Education Network℠ improves lives by catalyzing more direct and promising pathways between education and employment. Strada engages partners across education, nonprofits, business and government to focus relentlessly on students’ success throughout all phases of their working lives.

Its three-pronged approach addresses critical college to career challenges through strategic philanthropy, research and insights, and mission-aligned affiliates with the goal of strengthening America’s pathways between education and employment. Details about their approaches and resources are available here.

Other initiatives to look into:

In 2017, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation launched the Talent Pipeline Management Initiative, and now hosts a conference, Talent Forward, for enterprise solutions to closing the gap. For example, Ariel Corporation in Mount Vernon, Ohio, created its own Blue Chip training program and organizes career fairs for 7th graders and their families to inspire them to pursue highly technical vocational careers.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.