POLICY CIRCLE BRIEF

Mental Health

Introduction

CASE STUDY

Eric Grandon spent 20 years leading classified missions in the Middle East for the U.S. Army. After his experiences on tour in operation Desert Storm, Eric struggled to adapt to civilian life; he contemplated suicide and was diagnosed with PTSD.

The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs estimates 12% of Gulf War veterans and about 10-20% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans suffer from PTSD. Treatments usually include antidepressant medication or cognitive behavioral therapy, but Eric is one of the many veterans beginning to turn to beekeeping for relief.

Eric and his family own and operate Sugar Bottom Farm in West Virginia. He was the first person to sign up for West Virginia’s Warriors to Agriculture program, now known as the Veterans and Heroes to Agriculture program. He estimates that he has trained more than 700 fellow veterans on beekeeping. Another VA beekeeping program in Manchester, New Hampshire began in 2019 and has kept veterans socially connected throughout the coronavirus pandemic. “‘It gives you a chance to shut down and not think about the outside world. It shows me there is a way to shut my brain down to get other things accomplished,’” explains Army veteran Wendi Zimmerman.

In addition to VA programs, which are not offered throughout the country, nonprofits support veterans’ beekeeping endeavors. Heroes to Hives, a program through Michigan State University, offers veterans a community-building activity and “the opportunity to continue to serve their country as they transition from protecting our national security to our food security.” The University of Minnesota’s Bee Veterans program offers training to Minnesota residents, and is initiating a nation-wide effort for groups and individuals interested in supporting veterans in beekeeping. Bees4Vets, based in Nevada, also provides hands-on training for veterans and first responders suffering from PTSD.

Bees4Vets founder Ginger Genwick got started “after spotting a 1919 pamphlet written by the government that advocated beekeeping for veterans returning from World War I with shell shock.” Research has indicated time in nature is beneficial for mood disorders, but there is little research specifically on beekeeping as a form of therapy. Bees4Vets has teamed up with the University of Nevada to research how and why beekeeping seems to be beneficial for anxiety and depression.

U.S. Navy veteran Burt Crapo explains how beekeeping has impacted his life (1 min):

WHY IT MATTERS

Since the summer of 2020, about half of U.S. adults have reported “negative mental health impacts related to worry or stress from the pandemic,” up from about one-third of adults prior to the pandemic. The dramatic increase can be attributed at least in part to COVID-19, but the mental health crisis in America was growing long before the pandemic. Nearly 53 million U.S. adults (21%) experience mental illness each year, but fewer than half receive treatment.

Positive mental health allows people to cope with the stressors of life, work productively, and make meaningful contributions to society. Those suffering from mental health disorders may be prevented from realizing their full potential. Additionally, mental health impacts not only the individuals that are suffering but also their families, friends, workplace, or school. Mental illness takes its toll on vital institutions including the healthcare system, public safety and housing. This issue is complex and requires consideration of prevention, identification, intervention, treatment, and ongoing support.

Putting it in Context

UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH

Mental health includes emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, act, relate to others, make decisions, handle stress, and cope with change and challenges.

Mental illness refers to mental, behavioral, and emotional disorders that affect a person’s “thinking, mood, or behavior” such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In severe cases, mental illness interferes with major life activities.

Many people have mental health concerns occasionally, but when continuous and constant symptoms affect the ability to function, it becomes a mental illness. Mental health conditions are far more common than most people realize:

- More than 1 in 5 U.S. adults experiences mental illness each year;

- More than 1 in 20 U.S. adults experiences serious mental illness each year;

- 1 in 6 U.S. youths aged 6-17 experiences a mental health disorder each year;

- About 50% of all lifetime mental illnesses begin by age 14, and 75% by age 24.

For more information, see mentalhealth.gov, Mayo Clinic, and the National Association of Mental Illness.

Mental health disorders can affect anyone, from children in schools to adults in the workplace. But just because these problems are common doesn’t mean they are not complex. A single cause has not been identified, but there are established risk factors including family history, life experiences, biological factors such as chemical imbalances or traumatic brain injuries, drug use, feelings of isolation, and stress.

TED-Ed explains how susceptible our brains are to stress, which can lead to mental health disorders (4 min):

MEASURING MENTAL HEALTH DATA

An effective system that can track data is necessary to provide comprehensive information about the mental health of a population so as to allocate resources and determine the effectiveness of policies and programs. Common mental health indicators include suicide rates, hospitalization rates, resource utilization rates (such as number of psychiatric beds per capita), and self-reported use of mental health services or disorders. These mental health indicators do not always capture the broad spectrum of severity of mental illness. Suicide represents an extreme manifestation of distress. Hospitalization rates and resource use does not include those who receive outpatient or community services. Self-reported disorders may leave out mild cases or short-lived, isolated cases.

HISTORY

Ancient and medieval cultures treated mental illness as a personal problem at best, or demonic possession at worst. Many credit these early beliefs as the reason for the stigmatization that surrounds mental health disorders to this day.

In the 1700s, asylums were created to house those who were deemed dangerous due to lunacy. In those asylums, therapeutic approaches yielded positive results for individuals suffering from melancholia, now known as depression. According to John Cookson in Core Psychiatry, “The discovery that the institution itself could have a therapeutic function led to the birth of psychiatry as a medical speciality.” The term “psychiatry” was first coined in 1808, and therapeutic asylums became more common in the 19th century.

In the mid-1800s, the institutional inpatient care model emerged. In this care model, “patients lived in hospitals and were treated by professional staff,” which was considered the most effective way to care for the mentally ill because it allowed for increased access to services that many families struggled to provide.

Institutional-focused care at state hospitals did have its problems: they were typically underfunded and understaffed, and “drew harsh criticism following a number of high-profile reports of poor living conditions and human rights violations.”

In the 1950s, three forces drove the movement of people with mental illness from hospitals into the community: the belief that mental hospitals were cruel and inhumane; the hope that new antipsychotic medications offered a cure or decrease of symptoms; and the desire to reduce costs.

Emergency rooms are crowded with the acutely ill patients with long psychiatric histories but no plausible dispositions. Patients who are violent, have criminal histories, are chronically suicidal, have history of damage to property, or are dependent on drugs cannot be easily placed. They are often discharged back to the streets where they started.

DR. DANIEL YOHANNA

The Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963 drove deinstitutionalization and shifted funding away from “‘asylum-based’” care to community-based care through community health centers and community psychiatric teams. As with state hospitals, however, many critics say community systems are inadequate and underfunded. They claim the burden of caring for mentally ill individuals has shifted back to families. For more information on the history of mental health, visit Unite for Sight.

In this AMA Journal of Ethics article, Dr. Daniel Yohanna asserts that the current decentralized mental health system has “benefited middle-class people with less severe disorders” and left others “who are either poor or have more severe illness with inadequate services and a more difficult time integrating into a community.” Dr. Yohanna links underfunded community treatment options with high rates of arrests of people with severe mental illness.

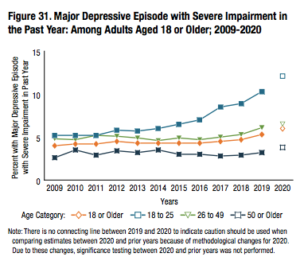

IMPACT OF MENTAL ILLNESS

According to 2020 data from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 52.9 million U.S. adults (21%) experience mental illness each year, but fewer than half receive treatment. NIMH also reports that females (25.8%) are more likely than males (15.8%) to experience mental illness and that rates of mental illness are highest among young adults ages 18-25 (30.6%), compared to adults age 26-49 (25.3%) and age 50 and older (14.5%).

In 2020, 14.2 million U.S. adults (5.6%) experienced serious mental illness, defined as mental illness that interferes with life activities. NIMH reports 64.5% of these adults received treatment, and that treatment rates were higher among females than males. Adults with serious mental illness are also more likely to be uninsured and are less likely to be able to afford mental health care than those without serious mental illness. In fact, according to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 35.5% (5 million) of those with serious mental illness did not get the care they needed, and only 46.2% (24.3 million) of those with any mental illness got the care they needed.

SUICIDE AND SELF-HARM

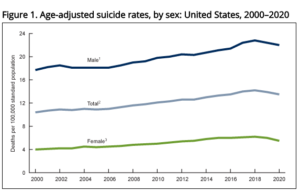

Suicide accounts for an estimated 800,000 deaths annually worldwide, although underreporting is likely. In the United States, the suicide rate has increased 30% between 2000 and 2020, from 10.4 deaths per 100,000 people to a peak of 14.2 deaths per 100,000 people in 2018, followed by a slight decline to 13.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2020. In 2019, there were nearly 2.5 times as many suicides (47,511) as there were homicides (19,141).

Suicide rates among males were about 3-4 times higher than those among females during the period from 2000 to 2020, and rates have increased the most among adolescents and young adults. The Department of Health and Human services classifies suicide as the second leading cause of death among individuals ages 10-34, and the tenth leading cause of death overall for Americans.

A related phenomenon is suicide contagion, defined by the Department of Health and Human Services as “the exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, one’s peer group, or through media reports of suicide and can result in an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors.” Exposure to suicidal behavior has been linked to increases in suicidal behavior among persons considered at risk for suicide, particularly for adolescents and young adults.

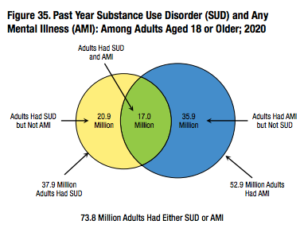

SUBSTANCE USE

Data from SAMHSA suggests that adults with mental illness are more likely than those without mental illness to be binge alcohol users, users of illicit drugs or marijuana, and misusers of opioids. A 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine estimated that Americans with mental health disorders were significantly more likely to use opioids than adults without mental health disorders (18.7% vs 5%). They estimated that Americans with mental health disorders (16% of the population that year) received 51.4% of all opioid prescriptions distributed. Fewer than 10% of people with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders received treatment for both, and more than 50% did not receive any treatment at all.

Data from SAMHSA suggests that adults with mental illness are more likely than those without mental illness to be binge alcohol users, users of illicit drugs or marijuana, and misusers of opioids. A 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine estimated that Americans with mental health disorders were significantly more likely to use opioids than adults without mental health disorders (18.7% vs 5%). They estimated that Americans with mental health disorders (16% of the population that year) received 51.4% of all opioid prescriptions distributed. Fewer than 10% of people with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders received treatment for both, and more than 50% did not receive any treatment at all.

HOMELESSNESS

An extensive survey by the Department of Housing and Urban Development conducted in 2015 found that 45% of homeless Americans had a mental illness, and 25% had a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression. Multiple analyses have found correlations between decreases in available psychiatric hospital beds and increases in homelessness in nearby areas. For example, studies in Massachusetts, Ohio, and New York have found that on average one-third of discharges from state mental hospitals become homeless within six months.

CRIME AND INCARCERATION

According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, law enforcement agencies use about 10% of their total budgets responding to and transporting persons with mental illness. In 44 states, at least one jail or prison holds more individuals with sever mental illness than the state’s the largest psychiatric hospital. Many experts and advocates see this as a consequence of failing to provide adequate treatment. “We have much too much relied on [jails] as sort of the de facto mental health treatment providers, which they’re not,” said Ron Honberg, an independent mental health consultant and former director of policy and legal affairs for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

COSTS

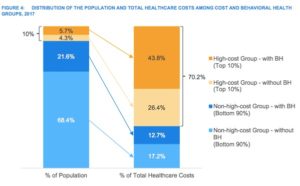

In the U.S., annual mental health care costs amount to more than $200 billion. A 2017 study looking at healthcare costs of 21 million commercially insured people found the top 10% most expensive patients of this group accounted for 70% of healthcare costs. In this high cost top 10%, 57% had mental health or substance abuse diagnoses. This means that this subgroup, roughly 1.2 million people, 6% of the studied population, contributed 44% of all healthcare spending for the full 21 million people. The average annual healthcare costs for high-cost individuals with behavioral health problems were almost $10,000 greater than costs for high-cost patients without behavioral health problems.

The following graph illustrates how different population segments contribute to healthcare costs:

Henry Harbin, MD, leading behavioral health expert and adviser to The Bowman Family Foundation, explains (6 min):

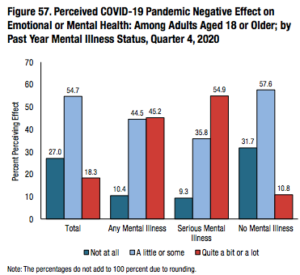

COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated mental health problems. Social isolation and uncertainty surrounding the future can increase feelings of depression and anxiety, and social distancing has made it more difficult to get treatment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that symptoms of anxiety and depression were three to four times more prevalent in June 2020 than in 2019. According to SAMHSA’s 2020 report, more than half the population of adolescents 12-17 and adults over 18 perceived negative mental health effects due to COVID-19. For all individuals ages 12 and older, 15% reported drinking more or much more than before the pandemic and 10.3% reported using more drugs than before the pandemic.

Some economic forecasts estimate “that the cost of treating widespread anxiety and depression will create a $1.6 trillion drag on the U.S. economy” due to lost productivity and medical expenses. Despite the prevalence and the individual and social repercussions, even in states with the greatest access fewer than half of youths and adults that need mental health services receive them.

On the opposite side of this, mental health professionals are also overwhelmed. In one 2021 survey of over 1,300 mental health professionals, nine out of ten said they were having difficulty meeting patient demand. In many cases, they are facing the same challenges as clients, and some have to cut hours because of home and life demands created during the pandemic.

The American Psychological Association’s (APA) 2021 Stress in America survey found that “Americans are struggling with the basic decisions required to navigate daily life as the effects of pandemic-related stress continue to take a toll[.]” Since the start of the pandemic:

- 32% of Americans said they are sometimes so stressed about the pandemic they struggle to make even basic decisions, such as what to wear or eat;

- 49% responded that the coronavirus pandemic makes planning for their future feel impossible;

- 22% admitted to procrastinating or neglecting responsibilities;

- 35% said they eat to manage their stress;

Additional data from a February 2022 survey from the APA shows:

- 87% of respondents agreed it feels like there has been a constant stream of crises over the last two years;

- 73% of respondents reported they are overwhelmed by the number of crises facing the world right now;

- 58% of respondents have experienced unwanted changes in weight;

- 23% of respondents are drinking more than they did before the pandemic.

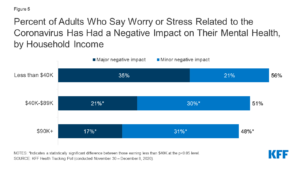

A January 2021 Kaiser Family Foundation report pooling data from both its Health Tracking Poll and from the Census Bureau found:

- 40% of U.S. adults have reported anxiety or depressive symptoms, compared to 10% in January 2019;

- 48% of non-Hispanic Black adults, 46% of Hispanic adults, and 41% of non-Hispanic white adults reported negative mental health impacts;

- Women with children were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depression than men with children (49% vs. 40%).

- Adults in households with lower incomes or job losses reported higher rates of mental illness symptoms than did adults in households with higher incomes or that have not suffered job losses (53% vs. 32%).

- Compared to the general population, essential workers during the pandemic have experienced:

- higher rates of symptoms of anxiety and depression (42% vs. 30%)

- substance use (25% vs. 11%)

- and suicidal thoughts (22% vs. 8%)

The Role of Government

FEDERAL

The federal government has expanded its primary roles within the healthcare system by regulating systems and providers, protecting the rights of consumers, providing funding for services, and supporting research and innovation.

Federal legislation for mental health applies to schools, insurance companies, treatment providers, and employers and can set in place regulations for systems and providers, or protections for the rights of individuals with mental health disorders. Examples include the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Rehabilitation Act, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and the aforementioned Community Mental Health Centers Act. Other federal actions can indicate government priorities, such as two Congressional Resolutions in the 1990s that recognized suicide as a national problem and prevention as a national priority.

The federal government has over 40 programs serving people with mental illness. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) are two of the largest programs, and substantial mental health services also fall under Medicare and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Additionally, federal funding matches state Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) spending, usually anywhere between 50 and 70% of costs, making Medicaid “the single largest funder of mental health services in the country.”

Other federal programs dedicated to child welfare, criminal justice, education, rehabilitation, and homelessness, to name a few, also offer mental health services. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is the lead agency that provides targeted funding to states to implement services for individuals with substance use disorders or mental illness. SAMHSA is also responsible for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

The 2022 SAMHSA budget allocates:

- $3.5 billion for Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grants (almost double the 2021 total of $1.8 billion);

- $1.5 billion for Mental Health Block Grants that support employment, housing, rehab services, and crisis stabilization services that are not usually covered by private insurance or Medicaid (roughly double the 2021 total of $758 million);

- $375 million for Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration for state-certified, community behavioral health and primary care organizations (a 50% increase over the 2021 total of $250 million);

- $125 million for Children’s Mental Health Services

- $180 million for suicide prevention programs (an increase of $78 million over the 2021 total).

Finally, federal spending also funds government agencies like the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) or SAMHSA to “lead research, administer grants, and educate the public about findings”. In 2020, the NIMH spending shows the government spent over $3.5 billion on mental health and an additional $1.1 billion on mental illness, with $600 million earmarked for depression, $236 million for anxiety, $143 million for PTSD, $520 million for serious mental illness, and $240 million for suicide and suicide prevention.

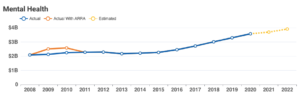

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, signed into law in December 2020, included $4.25 billion in funding for mental health and substance use services, an increase credited to complications caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The March 2021 American Rescue Plan Act also increased funding for these services, including an additional $1.5 billion each for the Community Mental Health block grant program and the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment block grant program (Note: ARRA spending is additional from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act).

STATE

State mental health systems are required to meet certain standards that the federal government sets, but after that “they are free to expand beyond what exists at the federal level and improve services, access, and protections for consumers.” For example, states can implement their own mental health “parity” laws, equal coverage laws that prevent health care service plans from discriminating, or minimum mandated mental health benefit laws, which require some level of coverage to be provided for mental illness.

States have also passed laws that address problems first responders and physicians encounter. Emergency Mental Health Hold laws, which “authorize certain first responders to take an individual experiencing a mental health crisis into a form of civil custody in order for them to be evaluated by appropriate mental health or medical personnel.” Duty to Warn laws exempt practitioners from maintaining confidentiality and require them to warn third parties of potential threats to a patient’s safety.

In terms of funding, all states receive federal support via Mental Health Block Grants and partial funding through Medicaid and CHIP (The 2022 federal budget allocates over $4 billion in block grants to the states. See your state’s SAMHSA grants). Some programs stipulate that states must spend a certain percentage of these funds in a certain way, such as the Mental Health Block Grants that require states to use at least 10% of the funds on early intervention. Besides these conditions, states do have the freedom to design and fund their own mental health systems, including state hospital and local services. Additionally, states can fund state-based academic institutions to help in research, which may be available on the websites of the academic institution or state health departments.

See how your state ranks in terms of access to care and mental health services.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

The coronavirus pandemic disrupted mental health services, including counseling and psychotherapy services, harm reduction services, addiction treatment, emergency interventions, access to medications, and school and workplace mental health services. It has affected everyone from children in schools to adults in the workplace, and continues to do so two years into the pandemic.

YOUTH AND SCHOOLS

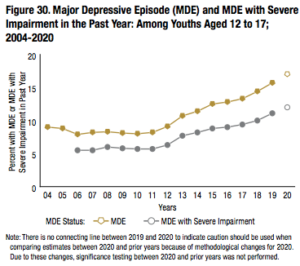

The pandemic “has hit children on multiple fronts. Many have experienced social isolation during lockdowns, family stress, a breakdown of routine and anxiety about the virus. School closures, remote teaching and learning interruptions have set back many at school.” From April to October 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that U.S. hospitals saw a 24% increase in the proportion of mental health emergency visits for children ages 5-11 and a 31% increase in children ages 12-17.

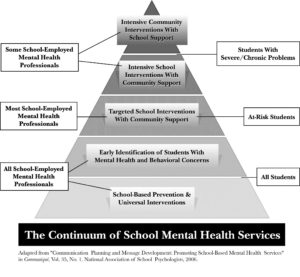

Educators play a critical role in identifying mental health disorders in America’s youth, and schools often offer key mental health services many children do not have access to elsewhere. But even prior to the pandemic, many believed schools were not entirely prepared for this responsibility. Teachers, for example, are uniquely positioned to notice behavior changes in students, but have extensive responsibilities and do not always have training in mental health issues.

Other faculty members including social workers, special education teachers, and school psychologists and counselors are trained to work with students experiencing mental health problems, but even these resources are spread thin. Shane Jimerson, professor in the Counseling, Clinical and School Psychology Department at UC Santa Barbara says that “demand is increasing exponentially and it’s harder and harder to keep up.” In California, the Department of Education reported schools have increased counseling staff by 30% in the past five years, bringing the ratio to over 600 students per counselor. The recommendation from the American School Counselors Association is 250 students per counselor, and the national average is 465 students per counselor. Besides staff, school resources include the Anxiety & Depression Association for America’s peer-to-peer online support groups, canine therapy such as K-9 Reading Buddies, or school programs such as the Bring Change to Mind High School Program.

Besides staff, school resources include the Anxiety & Depression Association for America’s peer-to-peer online support groups, canine therapy such as K-9 Reading Buddies, or school programs such as the Bring Change to Mind High School Program.

There is no “national blueprint for helping students cope with mental health conditions,” leaving states to innovate and create their own prototypes. The Massachusetts BRYT (Bridge for Resilient Youth in Transition) program, founded in the Boston area by the nonprofit Brookline Center for Community Mental Health, “has emerged as a successful model for helping kids re-enter school after a mental health crisis.” The Center works with schools to implement BRYT programs, staffed by school employees, and helps identify funding sources. In the 137 schools in Massachusetts that have implemented the program, 90% of students in BRYT programs remain on track for graduation. Florida is another state that has implemented extensive mental health plans state-wide, with individual plans in each school district, detailed appropriations lists, and compiled best practices.

ADOLESCENTS AND SOCIAL MEDIA

While one-third of all Americans ages 13-56 cite the pandemic as a major source of stress, Gen Z (46%) report the highest levels of life disruptions, compared with Millennials (36%) and Gen X (31%), particularly in areas of education, friendship, relationships, and the ability to pursue career goals.

Throughout the pandemic, Americans ages 12-25 have been reporting the highest levels of stress and mental health issues:

The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS) “is a multidimensional assessment and outcome-monitoring instrument used by the Center for Collegiate Mental Health counseling centers.” The chart shows trends in student self-reported distress upon entry to counseling services.

Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University, explains that among adolescents and young adults there has been an increase in major depression, suicidal thoughts, and psychological distress since 2010 as compared to the mid-2000s. She notes the trend is not the same among adults over the age of 26.

This increase has coincided with the widespread adoption of social media, which has prompted concerns that there is a potential link. Studies exploring how social media use might be associated with mental health concerns have reported mixed findings, but many reveal “a small but significant negative effect of social media use on mental health,” although experts are still trying to understand how, why, and for whom.

Some experts say social media can benefit adolescents and teens “by helping them develop communication skills, make friends, pursue areas of interest, and share thoughts and ideas.” On the other hand, over 70% of teens report that they have been cyberbullied at some point. A study in JAMA Psychiatry “found that adolescents who use social media more than three hours per day ‘may be at heightened risk of mental health problems, particularly internalizing problems.’” According to surveys from the National Center for Health Research, 40% of adolescent girls and 20% of adolescent boys report using social media for over 3 hours per day. One theory related to excessive social media use is that social media can disrupt sleep and circadian rhythms, which can lead to anxiety and depression. Some researchers have potentially connected frequent social media use with symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among adolescents, although more research is needed to determine causation and there are many confounding factors.

Some social networking sites including Facebook and Instagram have screening and intervention procedures for when users show signs of emotional distress, and mobile apps for mental health are very popular. At the same time, “Infinite scrolling and push notifications keep users constantly engaged; personalized recommendations use data not just to predict but also to influence our actions, turning users into easy prey for advertisers and propagandists.”

The World Health Organization and the Canadian Psychiatric Association established media guidelines to remind social media users to think about what they post, and how sharing certain graphic images or sensationalized stories can potentially be harmful to others. They recommend providing accurate information, links to helplines, affordable help options, and resources such as #chatSafe, a project that aims to formulate evidence-based guidelines to help young people communicate safely online about suicide.

ADULTS AND THE WORKPLACE

The indirect costs of mental health disorders, particularly lost productivity, may exceed spending on direct costs such as through health insurance contributions. In fact, the Work Outcomes Research and Cost Effectiveness Study at Harvard Medical School, sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health, investigated depression care management for workers at sixteen large companies. The study found workers assigned the intervention reported improved mood and increased productivity by about 2.5 extra hours per week (worth roughly $1,800 per year), compared to the control group. Intervention only cost $100-$400 per employee.

More and more workers have been reporting mental health problems related to the coronavirus pandemic. One Oregon-based insurance company survey found 46% of over 1,400 workers surveyed at the end of 2020 said they were struggling with their mental health, compared to 39% in 2019. Mind Share Partners’ 2021 Mental Health at Work Report found that:

- 50% of all employees have cited mental health reasons for leaving their jobs (compared to 34% in 2019). This includes:

- 68% of Millennials (50% in 2019), and

- 81% of Gen Zers (75% in 2019).

Healthcare workers that have been on the front lines for the past two years are experiences some of the highest levels of stress. A 2020 survey from Mental Health America found:

- 93% of healthcare workers were experiencing stress;

- 86% were experiencing anxiety;

- 76% were exhausted and burned out.

Another 2020 survey among physicians in the U.S. found:

- 58% reported feelings of burnout, compared to 40% in 2018;

- 22% know a physician who committed suicide, and 26% know a physician who has considered suicide;

- 18% reported increasing “their use of medications, alcohol, or illicit drugs as a result of COVID-19’s effects on their practice or employment situation.”

Employees are calling on their employers to take action: 91% of respondents in Mind Share Partners’ 2021 Mental Health at Work Report believe a company’s culture should support mental health.

Employers have responded by expanding access to virtual mental health and emotional well-being services, addressing cost barriers, wait times, and stigma that often prevent employees from receiving services. According to Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF) 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey, 40% of companies made changes including:

- “31% that increased the ways employees can tap into mental health services;”

- “16% that offered employee assistance programs or other new resources for mental health;”

- “6% that expanded access to in-network mental health providers.”

Almost 40% of the largest companies that participated in the KFF survey reported workers using more mental health services in 2021 than in 2020. Mind Share Partners survey found 47% of respondents believed their manager was equipped to support their mental health (39% in 2019) and 54% believed their company prioritized mental health (41% in 2019).

For example, Starbucks has offered employees free virtual therapy sessions, and Bank of America expanded telemedicine options for behavioral health and access to free emotional wellness mobile apps. BetterUp Inc., is a “fast-growing coaching and mental health firm” with a network of more than 2,000 coaches that is used by companies from Hilton to Chevron to Salesforce.

VETERANS

Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are the most publicized mental health challenges facing military veterans; an estimated 14-16% of service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq have PTSD or depression. Other issues equally harmful and prevalent include suicide, traumatic brain injury, substance abuse, and interpersonal violence.

Since 2012, suicide rates for active duty service members and veterans (30,000+) have outpaced those of combat-related deaths in post-9/11 conflicts (just over 7,000). The DoD reports that the suicide rate for veterans is 1.5x that of the general population, although this is likely an undercount because DoD data do not include reserve numbers or members of the National Guard. A 2021 report from the VA puts the rate at closer to 1.8x that of the general population.

Experts cite a few reasons to explain the rise in mental health concerns:

- The nature of warfare, from exposure to combat to the protracted length of war;

- Military culture, from rigorous training and schedules to the dominant masculine identity that makes asking for help during trauma difficult and maintains the idea that acknowledging mental illness may be viewed as a sign of weakness.

Congress provides $20 million annually to the DoD for suicide prevention programs and research, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) receives billions of dollars to combat suicide annually. In FY2021 $10.2 billion was dedicated to veteran suicide prevention. The Veterans Crisis Line has answered more than 6.2 million calls; more than 250,000 texts; more than 739,000 chats; and has made more than 1.1 million referrals to VA suicide prevention coordinators.

BARRIERS TO TREATMENT

STIGMA

The coronavirus pandemic and subsequent global challenges from war and inflation to reduced social support and school closures have pushed stress “to alarming levels” since early 2020. The unprecedented impact on mental health has brought the topic to the forefront of many conversations among policymakers, in schools, and in work places, although feelings of stigma do remain among certain segments of the population.

A 2018 BlueCrossBlueShield report found a 47% increase in depression diagnoses among 18-24 year olds between 2013 and 2016, and the increase was attributed to more individuals seeking help on account of the view that mental health is understood as an aspect of overall health. Peggy Drexler of the Wall Street Journal writes, “The stigma traditionally attached to psychotherapy has largely dissolved in the new generation of patients seeking treatment… today’s 20- and 30-somethings turn to therapy sooner and with fewer reservations than young people did in previous eras.”

In a 2019 American Psychological Association survey, 87% of respondents said that “a mental health disorder is nothing to be ashamed of,” but 86% also believed “mental illness carries a stigma” and almost 40% said they would view someone differently if they knew that person had a mental health disorder, indicating some stigma still remains. Usually, fewer than half of individuals diagnosed receive treatment.

Those who do seek care are most likely to do so due to related physical ailments such as gastrointestinal distress, sleep problems, or heart trouble. Stigma often prevents people from seeking treatment; Mind Share Partners survey found that while nearly two-thirds of employees are talking about mental health at work, less than half said their experience was positive or that they received positive or supportive responses.

Among military veterans, stigma is even more prevalent. In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, 83% of those reporting physical health problems in the past 12 months received treatments, compared to 42% of those who reported experiencing mental health problems. Among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, “My mental health problem would go on my record” and “I would be seen as weak” were the most frequently cited reasons for not seeking help.

PROFESSIONAL SHORTAGE

SAMHSA estimates there is a shortage of almost 4.5 million providers for behavioral health services in America. By 2025, SAMHSA predicts there will be shortages of marriage and family therapists, psychiatrists, mental health counselors, social workers, psychologists, and school counselors, based on the fact that professionals are retiring faster than they are being replaced and recent trends of increasing demand.

There are roughly 30 psychologists per 100,000 people and 16 psychiatrists per 100,000 people across the country. However, over 115 million Americans live in areas (particularly rural areas) where there are fewer than 5 mental health professionals per 100,000 people. More than 60% of rural Americans live in an area with such a mental health professional shortage. Meanwhile, more than 90% of all psychologists and psychiatrists and 80% of Masters of Social Work are exclusively in metropolitan areas.

The Atlantic investigates the hidden crisis in rural America (14 min):

COST AND INSURANCE

Affording treatment can also be a barrier; many insurance plans do not cover certain treatments, which makes getting quality care challenging. According to SAMHSA’s 2020 Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators survey:

- Among people aged 12 or older with a substance use disorder, almost 20% reported they did not receive care because they had no health care coverage and could not afford the cost of treatment;

- Among adults aged 18 or older wth a mental illness, 44.9% said they did not receive treatment because they could not afford the cost of care.

The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 “required all large-group employer insurance plans to cover mental health services at the same level as medical and surgical services, if they offered them.” This was not applicable to individual or small-group plans until the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed. Medicaid expansion has been associated with increased coverage for low-income adults with mental health conditions and lower out-of-pocket spending particularly for young adults with mental health conditions.

Even with the parity acts, and even though millions of Americans gained access to insurance through the Affordable Care Act, many top providers opt out of the insurance system and only accept private pay. Almost half of private psychiatrists don’t accept insurance, so receiving the right care can be both challenging and expensive. One area of expansion could come about due to the coronavirus pandemic; employers are expanding access to mental health services for their employees, with companies offering telemedicine options and virtual therapy sessions.

DRUG INDUSTRY

In the 1970s, there was a distinction between depression that should be treated medically and depression caused by “bad stuff going on in your life” that should be treated with talk therapy. When more pharmaceutical companies began marketing antidepressant drugs, more providers prescribed them to more patients. This meant more patients, no matter the severity of their mental health disorders, had access to pharmaceuticals, but it also removed the distinction.

Samantha Meltzer-Brody, director of the University of North Carolina’s Perinatal Psychiatry Program, explains that there has been “a dearth of new pharmacological therapies for mood disorders” since serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors came out in the 1980s and 1990s. Studies during the 1990s also showed antidepressants did not have much better results than placebos, and that in fact placebos were having strong effects. Most antidepressants alter brain chemicals, such as serotonin, but this may not be effective for all patients; only two of every 10 patients show signs of improvement that are significant compared to the placebo effect.

Samantha Meltzer-Brody, director of the University of North Carolina’s Perinatal Psychiatry Program, explains that there has been “a dearth of new pharmacological therapies for mood disorders” since serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors came out in the 1980s and 1990s. Studies during the 1990s also showed antidepressants did not have much better results than placebos, and that in fact placebos were having strong effects. Most antidepressants alter brain chemicals, such as serotonin, but this may not be effective for all patients; only two of every 10 patients show signs of improvement that are significant compared to the placebo effect.

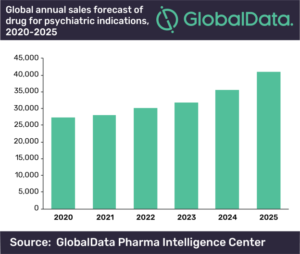

Over the course of the last decade, research into the causes of depression “in terms of brain chemistry as well as brain circuitry or brain physiology” have opened the door for new antidepressant drugs. In fact, a 2017 report indicated there are over 140 medicines in development for mental illness, including a once-a-day oral treatment with a novel design to rebalance brain function. If proven effective, it could help millions of patients who do not respond to standard antidepressant therapies. Global sales of drugs for mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder are projected to continue upward trends.

TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS

As the coronavirus pandemic rolled across the country, “2020 saw many innovations that harnessed AI and big data, smartphones and even our current habits to meet a raft of mental health challenges not seen in several generations.” These include prescription video games for young children with ADHD and virtual reality technology that has been linked to improvement in anxiety, phobias, and PTSD. AI chatbots have helped patients manage symptoms between appointments, and there are even apps that prompt patients to track their symptoms daily to share with providers, or apps that can analyze a patient’s voice for signs of emotional distress, acting “like an assistant who’s available 24/7 to support the patient and alert the provider when an intervention is needed.”

On the research side, Dr. John Torous at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School notes that technology can “generate a vast amount of data about the brain,” and AI can “find patterns that may help us unlock why people develop mental illness, who responds best to certain treatments and who may need help immediately.” All of this could create more personalized and preventive treatments.

Some experts believe AI and technological innovations can make treatment more affordable and accessible, especially due to the shortage of mental health professionals and the additional demand for mental health services brought on by the pandemic. Others have data privacy concerns, and note there hasn’t been extensive research on how well some innovations like AI chatbots actually work. And, as Dr. Adam Miner of Stanford School of Medicine points out, while AI systems definitely have the upper hand in terms of processing power and memory, there are things “humans do without effort in conversation that are currently beyond the most powerful AI system.”

ALTERNATIVE TREATMENTS

For patients who do not see significant improvement with antidepressant drugs, many studies point to the benefits of physical activity. Studies indicate regular exercise improves sleep, lowers blood pressure, and releases “natural cannabis-like brain chemicals” called endorphins that can enhance feelings of well-being. Spending time in nature – specifically, spending time in the woods, a Japanese practice called “forest bathing” – is also associated with lower blood pressure and heart rate, and decreased anxiety, depression, and fatigue.

Food can also have unexpected effects on mental health. The gut is often referred to as the “second brain” and “can operate on its own and communicates back and forth with your actual brain.” Connections between the gut and the brain, called the gut-brain axis, allow the brain “to influence intestinal activities” and allow the “gut to influence mood, cognition, and mental health.”

Dr. Erika Ebbel Angle discusses why the gut microbiome is the most important organ you’ve never heard of (11 min):

Creative outlets can be another source of relief from depression and anxiety, as engagement in things you enjoy doing “feeds your need for meaning and purpose.” Music can increase dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin levels in the brain, and studies show music and art can alleviate pain and help manage stress. Music therapy is often used for patients suffering from depression and anxiety, and is even used for patients on the autism spectrum and for people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

In recent decades, studies investigating the benefits of mindfulness and meditation have found meditation can improve sleep, improve symptoms of depression and anxiety, and even improve chronic pain. Meditation “has consistently been shown to reduce cortisol and catecholamine levels (such as epinephrine and norepinephrine) that may otherwise trigger biologically-based anxiety responses.”

Finally, while not exactly a treatment, research has shown that “social support” such as that from friends, family, and faith-based communities “wards off the effects of stress on depression, anxiety and other health problems.” Keith Humphreys, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and Stanford University, explains that social and emotional support is the basis for Alcoholics Anonymous. Similarly, The Phoenix helps those in recovery from substance abuse “find strength and a new community of friends” by offering free organized activities such as yoga, crossfit, paddleboarding, art classes, climbing, and biking.

COMMUNITY-DRIVEN SOLUTIONS

Community provides a sense of belonging and purpose through common interest, beliefs, and values. Particularly for “someone with mental illness who is already experiencing the common symptoms of loneliness and isolation,” community is critical to feeling supported. Communities can also be the catalyst to reduce stigma and embrace alternative treatments such as promoting exercise, focusing on safe streets and parks for all to enjoy, fostering community connections with events, and offering programs such as meditation or music and art activities in schools and recreational centers.

For this reason, community organizations are highly influential, particularly among youth and especially in terms of prevention. In Tampa Bay, Florida, Frameworks “empowers educators, youth services professionals, and parents and guardians with training, coaching, and research-based resources to equip students with social and emotional skills” to help them face challenges and potentially uncomfortable emotions in constructive ways. See more about Frameworks from students and teachers.

Also in Florida, first lady Casey DeSantis announced a “resiliency initiative for Florida schools” that partners with Florida sports teams and athletes to “‘rethink and reframe the way we talk about mental wellbeing in schools.’” In Chicago, the Mindfulness Leader educational program helps young leaders develop skills including self-awareness, self-management, and interpersonal and social awareness.

INTEGRATION OF SERVICES

The availability and integration of mental health services into communities “can play a crucial role in promoting mental health awareness, reducing stigma and discrimination, supporting recovery and social inclusion, and preventing mental disorders,” thus increasing positive clinical outcomes.

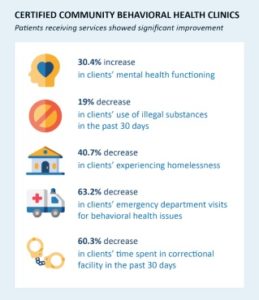

Community interventions emphasize multi-sector partnership among community members, organizations, and social services. There are a number of programs supported by the federal government and managed at the local level, including Coordinated Specialty Care and Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, but implementation requires local-level knowledge and community engagement.

One example is the Collaborative Care Model, which brings together primary care providers, care managers, and psychiatric consultants to provide care to and monitor patients. Integrating the services has shown improved clinical outcomes as well as reduced healthcare costs; one study found roughly $6.50 in savings for every $1 in spending.

Another example is housing programs. Housing programs tend to be competitive and difficult to access for individuals with mental illnesses, but supportive housing (“a number of rental apartments in one location with 24-hour crisis support services on-site”) may help. In California, homeless persons placed in supportive housing spent 57% fewer days in psychiatric hospitals over the course of one year than did homeless persons not in supportive housing. Another study from the University of Pennsylvania found “homeless people with mental illnesses placed in permanent supportive housing cost the public $16,000 less per year for emergency room services, jails, and psychiatric hospitalization.”

The Bipartisan Policy Center considers legislative and regulatory policy recommendations to support the integration of primary and behavioral health care services.

EMERGENCY CARE

Many communities face challenges in their crisis services, which are often “‘inconsistent and inadequate’” because they tend to rely on over-burdened 911 emergency systems, police response and transport, and hospital emergency departments. One successful model in California, known as the Alameda Model, was developed because the mental health care system in California was “fragmented and underfunded,” and emergency departments took on most of the burden of care. The Alameda Model established a dedicated psychiatric hospital with a crisis stabilization unit, expediting transfers from local emergency departments to the psychiatric hospital and reducing patient wait times for psychiatric care by over 80%.

Another new means of emergency response has been implemented in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where the likelihood of incarceration over hospitalization for people with mental illness is 3:1. The city of Albuquerque created another branch of public safety when residents call 911: behavioral health responders. Instead of a pilot or temporary program, behavioral health is its own standalone department separate from police and emergency medical services.

Similarly, CrisisNow, led by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, provides “communities a roadmap to safe, effective crisis care that diverts people in distress from the emergency department and jail by developing a continuum of crisis care services that match people’s clinical needs.” The program aims to provide more immediate and targeted help for people suffering a mental health crisis, and cut costs by reducing the need for psychiatric hospital bed usage. In Maricopa County, Arizona, Crisis Now is estimated to have saved state hospitals $260 million in inpatient acute care expenses.

Such programs are important for reducing the burdens on hospital systems while still getting patients the care they need, particularly because in many cases insurance companies may not provide full coverage, or may deny coverage, unless there is hospitalization to substantiate a diagnosis and need for treatment.

988 HOTLINE

In October 2020, lawmakers passed the law that would change the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number from a 10-digit number to a 3-digit number, 988. In 2020, more than 180 local call centers answered almost 2.5 million calls and provided support and connection. Changing the number has been a goal of the Federal Communications Commission, and has the support of carriers including AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon.

There are concerns that the network will not be up and running for the scheduled July 2022 launch, mainly due to staffing and funding issues. Nonprofits manage several hotlines through call centers and rely on paid counselors and volunteers; a SAMHSA report to congress said the system was understaffed. Taking on more staff is difficult, as centers have very small budgets to begin with. The October 2020 law gave state lawmakers the option to raise money for call centers the same way as with 911, with a monthly fee on phone bills. The fees would also fund mobile response teams, but many lawmakers are wary of adding new taxes and only four states have authorized the phone bill charge.

POLICE TRAINING

A 2019 Harvard Report found that data about police shootings and individuals with mental health conditions was very limited, but the available indicated a significant portion of individuals killed by police had some kind of mental health condition, likely because police are the first to respond to calls for help but are not often properly trained to address a mental health crisis. More and more police departments at the state and local level are countering this by implementing crisis intervention training; though expansion is slow, there are 2,800 such programs across the country.

Mobile Crisis Teams and Co-Responder Teams are services that have also been successful in local communities by relieving police officers. Denver’s STAR (Support Team Assisted Response) Program includes a mental health clinician and a paramedic to address low level incidents such as mental health episodes “that would have otherwise fallen to patrol officers with badges and guns.” Teams responded to 750 calls in the 6 months between June and December 2020, connecting people to services like shelters, food aid, counseling, and medication.

The Policy Circle’s Understanding Law Enforcement Brief takes a closer look at the heavy burden that falls on law enforcement personnel when it comes to addressing mental health issues in the community.

Conclusion

When individuals struggle, society as a whole struggles; the societal repercussions of mental health disorders are seen in lost economic productivity and expensive health system costs. Especially due to the coronavirus pandemic, these problems have only worsened. People with mental illness should have long-term treatment and support so they may lead a life to their full potential in their community.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about mental health

- Do you know the state of mental health in your community or state?

- What are your state’s laws? How much does your state receive in SAMHSA grants?

- Is there a coalition or task force in your community, or does one need to be formed?

- What state associations exist?

- Are there local organizations or programs that offer resources or community-based treatments, or does one need to be started?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of coalitions or task forces in your state?

- Who is your State Mental Health Commissioner?

- Find a local National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare member organization.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

- Who is called when there is a mental health crisis in your community?

- What type of training do the police receive?

Reach Out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state, including:

- Mental Health America local affiliates.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness local affiliates.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar and your local community calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Find out what kind of mental health coverage is offered with your insurance plan.

- Investigate the ratio of school counselors available in your school district. What kind of resources does your local school offer?

- Investigate the ratio of mental health professionals in your area.

- Talk to local law enforcement officers or first responders to understand the challenges they face with mental health emergencies.

- Is there an opportunity for a community collaboration program across multiple sectors, if one does not already exist?

- If one does not already exist, start a conversation.

- Communicate with local organizations that address mental health and see if there are opportunities to volunteer.

- See if there is a need or opportunity to share relevant resources with your local elected officials.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

- Mentalhealth.gov: National and local organizations

- Active Minds, a nonprofit “dedicated to utilizing the student voice to raise mental health awareness among college students.”

- Jed Foundation, which focuses on emotional and mental health among teens, young adults, and college students

- The American Institute of Stress

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center

- Disaster Distress Hotline

- Veteran’s Crisis Line

- Crisis Text Line

- TED: Feed Your Mental Health

- TED: How your belly controls your brain

Newest Policy Circle Briefs

The First-Time Voter Guide

Assessing Candidate Guide

Women and Economic Freedom

About the policy Circle

The Policy Circle is a nonpartisan, national 501(c)(3) that informs, equips, and connects women to be more impactful citizens.