Introduction

Review the Executive Summary for this brief.

Since the beginning of 2020, America has faced unprecedented challenges: impeachment hearings, COVID-19 and the ensuing shutdown of the U.S. economy in the midst of an election year, a historic surge in unemployment, and racial unrest resulting in mass protests around the world. Increasingly, there are questions about the role of public and private institutions from government and police to academia and the media. These questions are followed by calls to reform these institutions that make up the fabric of our daily lives. In the midst of such rapid change, the deluge of information and misinformation has been staggering. Americans could once rely on the accuracy of data from established sources and institutions, but now pervasive distrust undermines the authority and credibility of institutions, elected officials, and the media. Most importantly, distrust amongst communities and even neighbors creates more division, hampering the ability to collaborate to find solutions and build opportunities for all Americans.

Defining Trust

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, the key components of establishing trust in institutions and leaders are:

- Honesty: leaders will not benefit themselves at the expense of regular people and will take responsibility for their actions

- Fairness: leaders will have people’s best interests in mind and work for a better future for all individuals, families, and communities

- Purpose: leaders will handle resources responsibly in efforts to solve the country’s problems

- Vision: leaders are competent and capable of bringing about change

Why it Matters

When citizens lack trust in each other and institutions, “they are less likely to comply with laws and regulations, pay taxes, tolerate different viewpoints or ways of life, contribute to economic vitality, resist the appeals of demagogues, or support their neighbors… They are less likely to create and invent.” Citizens will be hesitant or even unwilling to cooperate freely if they do not believe others are responsible or trustworthy, or believe their rights are guaranteed and protected by society’s institutions.

When citizens lack trust in each other and institutions, “they are less likely to comply with laws and regulations, pay taxes, tolerate different viewpoints or ways of life, contribute to economic vitality, resist the appeals of demagogues, or support their neighbors… They are less likely to create and invent.” Citizens will be hesitant or even unwilling to cooperate freely if they do not believe others are responsible or trustworthy, or believe their rights are guaranteed and protected by society’s institutions.

Free societies are those that rely on “the basis of mutual trust and cooperation between individuals,” each of whom accepts “rules of interpersonal behaviour voluntarily.” Trust instills in individuals a sense of responsibility “to use their capacities in the best possible way to better serve society.”

Trust is also “the basis upon which the legitimacy of governments is built.” According to the Institute of Economic Affairs, the role of government “is to protect our freedom against violation by others – and to extend it to where it does not fully exist and enlarge it where it is incomplete.” Citizens’ belief that the government “will punish those who fail to respect personal property,” for example, is part of why they are willing to buy property and respect the property of others.

Governments only have this ability because they “have the consent of the governed, and are themselves governed by rules to prevent them exploiting their authority.” This goes beyond having trust in particular candidates, parties, or policies and refers to a general trust in institutions and the rule of law. The Institute of Economic Affairs outlines the importance of the rule of law in a free society in this video (2 min):

In summary, when citizens trust each other and the fundamental societal institutions, they cooperate freely and willingly for mutual benefit. Through the combination of trust, responsibility, and freedom, society prospers and people generally find meaning in their lives.

The State of Trust in America

Government

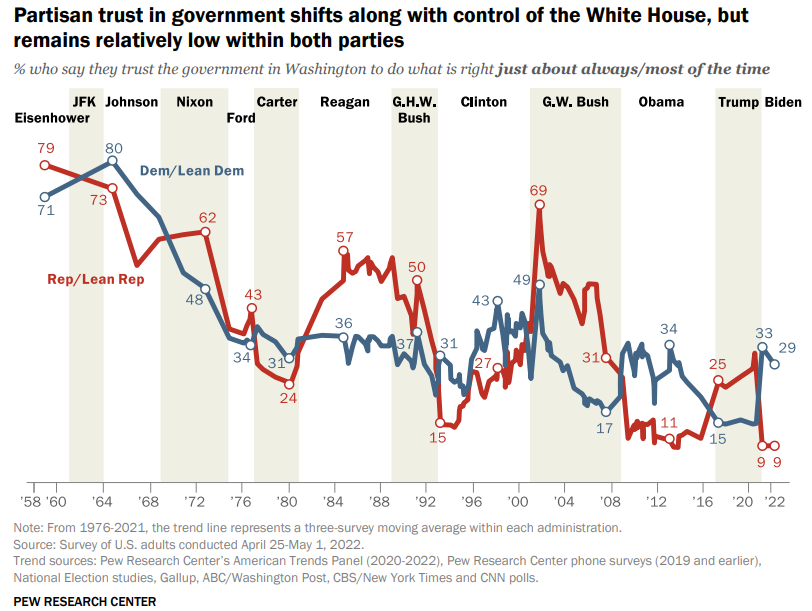

American National Election Studies (ANES) began asking about trust in the federal government in 1958, when 75% of the population demonstrated trust in government. These levels of trust eroded during the late 1960s and 1970s, reflecting the turbulence of the Vietnam War, Watergate, and economic struggles. During the 1980s and 1990s, trust in the government fluctuated, tending to correlate to good economic growth. It reached a three-decade high shortly after the 9/11 attacks, but since 2007 fewer than 30% of respondents have said they can trust the federal government “always” or “most of the time.” Americans’ trust in government tends to vary on partisan lines based on which party controls the White House, but trust in Washington has not recovered from the 2007 financial crisis.

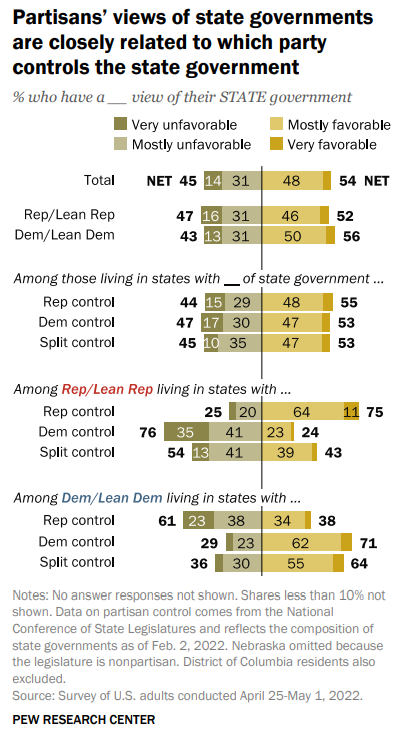

Americans are much more positive about smaller levels of government closer to their communities. According to a 2022 Pew Survey, about a third of Americans view the federal government positively, whereas state (54%) and local governments (66%) were viewed positively by majorities of respondents. How Americans feel about their state governments’ performance is closely tied to which party controls their state at any given time. Many Americans appear disengaged from state-level politics, and don’t cite specific issues where their state government is doing well or poorly. In the Pew Survey, half of respondents didn’t know or refused to answer when asked where their state government is doing a good job. When asked whether their state government is doing a bad job and could improve, nearly 40% said don’t know/refuse to answer, and among people who did answer, infrastructure (12%) and education (7%) were the most common issue areas.

America has not been alone in this respect; a 2017 global survey by Pew Research of 38 countries found a median of only 14% of people around the world say they trust their national government “a lot.” According to Gallup World Poll, between 2006 and 2017, 26 of 38 Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries saw declines in overall levels of trust in national governments, with some seeing declines of over 20%. In 2020, just over half (51%) of citizens trusted their government and the January 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer found only about 40% of the global population trust government leaders and believes government can coordinate effective responses to solve societal problems.

Reasons for declining trust in national governments include:

- “public- and private-sector corruption”

- “poisonous public rhetoric”

- “governments’ inability to provide essential security and human services”

- “breakdowns in the rule of law”

- “rising economic inequality”

- “perceptions that neither individual voices nor votes matter”

- “the sense that elites and the powerful have rigged the system”

- “volatile media and social media climate”

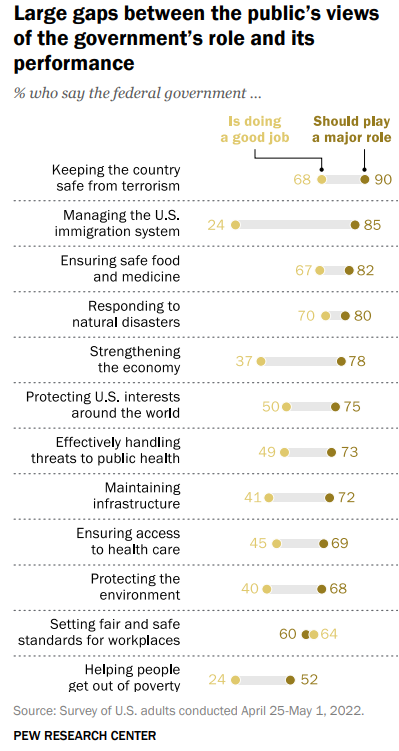

Large majorities of Americans from both parties tend to agree about areas where the government should play a major role, though opinions of how well the government is doing vary. The areas where there is consensus about that the government should play a major role, but isn’t doing a good job, are managing the immigration system (61%), strengthening the economy (41%), and maintaining infrastructure (31%).

Trust in Law Enforcement

Trust and feelings of safety are interconnected; strong relationships and mutual trust between police and communities are necessary for maintaining public safety and helping individuals feel secure.

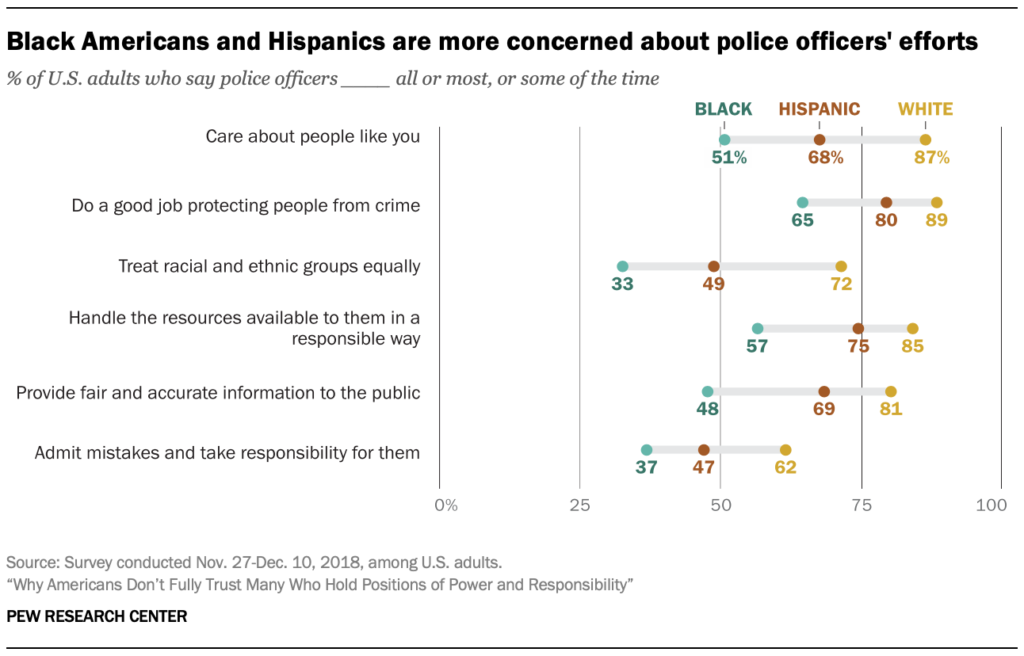

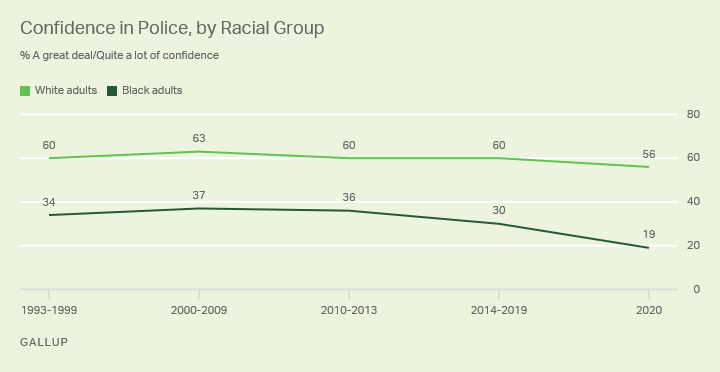

A December 2018 Congressional Research Service report found that overall confidence in the police declined between 2014 and 2015 after “high-profile incidents in which men of color were killed during confrontations with the police,” reaching a low of 52%. By 2017, the numbers had risen, with 57% of Americans said they had a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the police, which matched a 25-year average based on Gallup polling. Additionally, in 2018, PEW Research found roughly 80% of U.S. adults said police officers care about people and handle resources responsibly some or most of the time; over 70% said police officers provide fair and accurate information to the public some or most of the time; and 65% said police officers take responsibility for their mistakes some or most of the time.

The 2021 American Community Life Survey found 23% of respondents have a great deal of confidence in their local police, and 51% have a fair amount of local police. At the same time, 61% of Americans believe police officers treat Americans differently based on their racial or ethnic background.

When broken down by demographic group, trust in police differs from these overall results. According to the 2021 American Community Life Survey, 57% of Black Americans, 58% of Asian Americans, 65% of Hispanic Americans, and 81% of White Americans trust police in their communities at least a fair amount.

The 2021 American Community Life Survey found 60% of Asian Americans, 66% of Black Americans, 69% of White Americans and 76% of Hispanic Americans want more regular policing in their communities, with 29% of Black Americans and 24% of Hispanic Americans strongly favoring increased policing. Jason Riley, WSJ editorial board member and fellow at the Manhattan Institute, says national conversations about better policing must acknowledge communities with high crime rates to understand the simultaneous mistrust of police and desire for more policing.

For more, see The Policy Circle’s Understanding Law Enforcement Brief, or watch The Policy Circle’s Virtual Discussion on Understanding Law Enforcement and Policing in America:

Trust in the Private Sector

According to a 2020 Morning Consult poll, 55% of Americans say they trust the average American company, but 60% of U.S. adults say corruption is widespread in business. The 2020 Gallup Confidence in Institutions survey found small businesses in particular have Americans’ trust, with 75% of U.S. adults saying they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in small businesses. This held in 2021, with family-owned businesses being the most trusted business institution according to the Edelman Trust Barometer. Only 19% of Americans expressed “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of trust in big businesses.

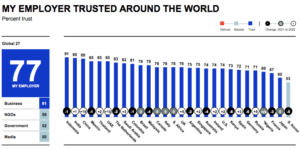

Even so, the Edelman Trust Barometer in January 2021 revealed businesses are the only institution seen globally as both ethical and competent, thanks to trust in local employers. The January 2022 Barometer showed businesses were the most trusted institution, with over 40% of people saying they want more business engagement on societal issues. Two-thirds of all respondents said “CEOs should take the lead on change rather than waiting for the government to impose it.” On the whole, businesses can continue gaining public trust by guarding information, embracing sustainability, and taking precautionary health and safety measures for employees.

Trust in Science & Academia

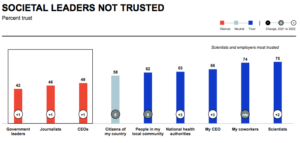

The National Science Foundation found that levels of trust in science have held stable since the 1970s, demonstrated in the chart below. Among U.S. adults, 84% express confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public, with an average 40% of Americans expressing “a great deal of confidence” in leaders of the scientific community while less than 10% have expressed “hardly any” confidence. Worldwide, the 2022 Edelman Barometer found scientists were the most trusted group of individuals, compared to government leaders, coworkers, CEOS, journalists, and community members.

The General Social Survey and National Science Foundation found large majorities of Americans believe scientists work toward the public good and believe scientists want to make life better.

The General Social Survey and National Science Foundation found large majorities of Americans believe scientists work toward the public good and believe scientists want to make life better.

A 2019 Pew Research survey found a majority (57%) U.S. adults said they trust scientific research findings, but specifically when data is openly available to the public. Almost six in ten (58%) of Americans have lower trust when research is funded by an industry group.

For more on trust in the healthcare system, see The Policy Circle’s brief on Health Disparities and Determinants of Health.

Trust in Media

Most Americans (84%) believe the news media is important to democracy, and focus on the media’s role to “provide accurate and fair news reports,” “ensure Americans are informed about public affairs,” and “hold leaders accountable for their actions.” At the same time, trust in the media has been falling consistently over the past two decades. This aligns with what Columbia Journalism Review calls “a profound shift in journalism,” when “ journalism began to embrace the necessity of interpretation.” This shift “places great responsibility on readers to discern for themselves the difference between what can be trusted as factual and what represents a reporter’s judgment,” says Michael Schudson of Columbia Journalism School.

In June 2021, PEW Research reported 58% of U.S. adults say they have at least some trust in information that comes from national news organizations. This is the smallest share over the past 5 years of asking the question; in late 2019, it was 65%. Only 12% express a lot of trust. For local news, 75% of Americans say they have at least some trust, down from 79% in late 2019.

The 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer revealed that globally, 35% of people trust search engines, traditional media, and social media. Majorities of respondents cite bias (75%) and inaccuracy (66%) as reasons for declines in trust; the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer found concerns about false information reached an all time high of 76%. Majorities of Americans also say their trust in the media is limited by the lack of media’s transparency in how stories are produced, where there are conflicts of interest, and where funding comes from.

For social media in particular, Americans are fairly consistent in their opinions. PEW Research found that even though over half (53%) of U.S. adults say they often or sometimes get news from social media, only 40% of those news consumers expect the news they see to be accurate. Roughly half of Americans believe social media has a negative impact on society (53%), as does targeted advertising (50%). A 2022 Knight Foundation report found majorities of Americans believe social media divides society:

Almost 70% of Americans do not trust social media companies to determine which posts on their sites should be labeled as inaccurate. Big Tech companies such as Amazon, Facebook, and Google are falling further out of favor with Americans; in early 2021, Gallup reported only one in three Americans has a positive view of Big Tech companies, a decline from 46% in August 2019. Over the same time period, the percentage of Americans who want more government regulation of Big Tech companies rose from 48% to 57%.

Trust in Communities and Each Other

In Norway, Sweden, and Finland, over 60% of residents think most people can be trusted. Halfway around the world, less than 10% of residents in Columbia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru believe this. Overall, the 2021 and 2022 Edelman Trust Barometers found people worldwide have more trust in their fellow citizens, coworkers, and employers than they do in CEOs, journalists, and government leaders as illustrated by the chart below:

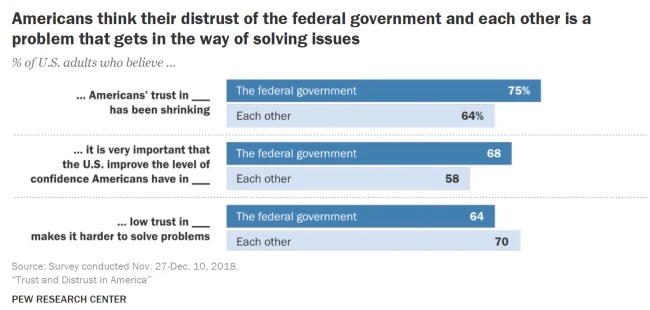

In the U.S. levels of trust are not as high as global averages, with approximately 37% of Americans believing “most people can be trusted” and 62% saying people “need to be very careful” around others, according to the World Values Survey. A 2019 PEW study of Trust and Distrust in America found Americans’ trust in each other has deteriorated in the last two decades. This lack of confidence can extend into all sectors of the community, from government to schools to the environment. The 2022 Edelman Barometer found most individuals developed closer bonds with their coworkers and neighbors, but have less trust in people from other countries, regions, and states.

“Empathy as well as generally attempting to understand and to help each other are all at disturbingly low levels…” – 44 year old male, PEW Research survey respondent

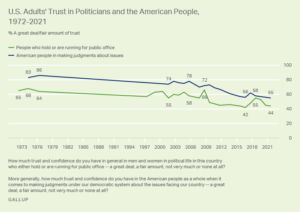

According to an October 2021 report from Gallup, “Americans’ trust and confidence in the American people themselves to make judgments under the democratic system remains quite low,” at 55%. This share was at least 80% throughout the 1970s, in the 70% range during the 2000s, and has been under 60% in six of seven years since 2014. It also correlates to trust in government, as illustrated in the following chart:

Impact of the Coronavirus

Government

FiveThirtyEight reported in April 2020 that about 56% of Americans were “at least somewhat confident” in the government’s ability to handle the outbreak and share accurate information, and that same month an Ipsos/USA Today poll found 41% of adults have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust specifically in Congress’s ability. Overall trust in the national government rose slightly from 43% in January to 46% in April of 2020. These polls show Americans’ trust in the government increased after the start of the coronavirus pandemic, which matches global trends: the May 2020 Edelman report found worldwide increases in trust in government, making it the most-trusted institution for the first time.

These findings support the “‘rally ‘round the flag’ phenomenon in which citizens rally around their leaders during times of crisis,” but such increases in support and confidence are usually temporary. In June of 2020, Northwestern University reported the share of Americans who believed the federal government was “reacting about right” to the coronavirus pandemic had fallen from 53% in April to 44% in late May. As of August 2020, 62% of Americans said, “the U.S. response to the coronavirus outbreak has been less effective than that of other wealthy nations.” The January 2021 Edelman report also revealed the “spring trust bubble” in government had burst, with global trust levels falling back to what they were prior to the pandemic-prompted trust increase.

After increasing at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, trust in local government has also slipped. The May 2020 Edelman report found trust in local and state governments rose from 54% in January to 66% in April. By August, the share of Americans who believed their state and local governments were handling the pandemic well had fallen from 70% and 69% in April to 56% and 60%, respectively.

Law Enforcement

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, the death of George Floyd at the hand of police officers in Minneapolis on May 25 sparked nationwide protests against excessive use of force and racial bias in policing. In June 2020, an Axios-Ipsos poll found 77% of White respondents said they trust local police to have their best interests in mind, compared to just 36% of Black respondents. A Marist poll that same month found similar results: 70% of White respondents and 31% of Black respondents said they have “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of confidence in their communities’ police officers to treat Black and White people equally. For the whole population, Gallup’s 2020 Confidence in Institutions survey found confidence in the police fell to 48% in August 2020, “marking the first time in the 27 year trend that this reading is below the majority level.” This rose to 51% in 2022, still slightly below historical averages.

Science & Academia

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, Americans indicated they “overwhelmingly trust the CDC” to handle the pandemic and share accurate information, with total trust for the agency around 80%. The share of Americans believing the CDC and other public health officers are doing an excellent or good job has since fallen, hitting 63% as of August 2020. At the local level, Americans’ belief that “hospitals and medical centers in their area are doing an excellent or good job in responding to the coronavirus outbreak” have held steady since May, at around 88% of Americans.

A PEW Research survey conducted in late April and early May found trust and confidence in medical scientists and scientists had increased since the outbreak. Additionally, 60% of Americans said scientists should take an active role in public policy debates on scientific issues, and 47% said they believe “scientific experts are usually better at making good policy decisions about scientific issues than other people.”

Media

Worldwide, there was an increase in trust in news sources at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Despite this all-time high, the media is still the least trusted institution behind government, NGOs, and businesses; according to the May 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer, 67% of people “worry that there is a lot of fake news and false information being spread about the virus.”

In the U.S. specifically, Pew Research found 89% of Americans were following the media “very” or “fairly” closely in March 2020, but 62% thought the media was greatly or slightly exaggerating. An April 2020 Ipsos/USA Today poll found 46% of Americans trusted the media to report accurately on the coronavirus, and an equal 46% did not. An August 2020 Edelman report found about half of Americans (49%) were getting most of their information about the coronavirus from major news organizations, and 46% of Americans say “they will never believe information about the coronavirus” if the only place they see that information is on social media.

According to Harvard University’s NeimanLab, what the general public reads or sees in the media heavily influences their opinions about current events, from the coronavirus to protests to social movements. Since the early stages of the pandemic, social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have seen growth and increases in usage as people search for information and ways to remain connected, meaning these platforms are all the more influential. Says Nathaniel Persily, Stanford law professor and co-director of the Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center, “‘There is a fight on social media as to how to portray the events on the ground’,” so protests have “turned into an online battle of opposing views.”

Private Sector

Gallup’s 2020 Confidence in Institutions survey found far more Americans have confidence in small businesses (75%, up from 68% in 2019) than they do in larger businesses (19%, down from 23% in 2019), and believe big businesses should be doing more. The May 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer found 78% of respondents said it is businesses’ responsibility “to ensure their employees are protected.” Additionally, a majority of respondents (65%) across eleven countries including the U.S. believe CEOs “should take the lead on addressing the pandemic rather than waiting for government to impose restrictions and demands on their businesses.” This held in the 2022 report, with 81% of respondents saying “CEOs should be personally visible when discussing public policy with external stakeholders or work their company has done to benefit society.” As of 2022, the Edelman Trust Barometer demonstrated majorities of people still trust their own coworkers and employers more than almost anyone else.

How to Build Trust

In the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, 64% of respondents agreed with the following statement: “People in this country lack the ability to have constructive and civil debates about issues they disagree on.”

“Trust builds when people feel they are part of a community- or society-wide enterprise that takes their concerns and voices into account.” As Harvard Business School Professor Frances Frei presents, trust depends on communicating quality logic, empathy, and authenticity. These provide the foundation on which to build trust in leadership, and engage citizens to solve problems in their communities and society. Watch Professor Frei’s entire explanation on how to build and rebuild trust (15 min):

Government

The Institute of Economic Affairs reminds us, “In a free society, the government has responsibilities to us… It is there to serve the citizens – not the other way around.” The government is an entity formed by the people, and as such citizens have the responsibility not only to vote for elected officials, but also to hold those officials accountable and demand transparency once they are in office.

For more on understanding the role of government and how government functions, see The Policy Circle Briefs on the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the U.S. Constitution.

Citizens can also connect with elected officials regarding policies that are working and policies that need to be fixed or implemented by encouraging localized, public policy solutions that best serve the needs of their communities. Public policy may seem like a difficult world to step into, but elected officials are only human and need feedback from their constituents on how policies are impacting real people. Here are questions to consider asking when developing and analyzing public policy:

Loading...

Loading...

This insightful video from Rohit Malhotra considers the value of local conversation and human interactions when rebuilding trust in institutions and in each other (17min):

Law Enforcement

Dr. David J. Thomas, Ph.D., professor at Florida Gulf Coast University’s Justice Studies Program and former police officer, believes the greatest challenge facing police “is regaining the trust of those that we serve.” Misunderstandings between police and citizens, he says, have given rise to an isolated police culture in which few officers are held accountable for violations. Those who do face discipline “are often allowed to resign in lieu of termination,” so they may be hired by another agency.

As citizens, some avenues of engagement include reaching out to both police officers and constituents in your community, or supporting and volunteering with groups working to bridge gaps and rebuild trust and cooperation between communities and law enforcement personnel. Researching policing reform options, such as use-of-force training, and the facts driving them is another way to start becoming more involved and better understand the situation.

Get started with The Policy Circle’s brief on Understanding Law Enforcement.

Science & Academia

Majorities of U.S. adults indicate they are more trusting of scientific studies when the data is available to the public or has been reviewed by independent committees, and they are less trusting when they know industry funding was involved in studies. Researching and getting involved in science-focused initiatives, task forces, and commissions in your community is a way to become a careful consumer of science. Ask questions about research and how information is disseminated.

Private Sector

According to the January 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer, ethics is the most important component for companies to build trust. This finding held for Edelman’s May 2020 update, in which the public indicated businesses can maintain or increase levels of public confidence and trust. Majorities of the respondents said businesses can do so by donating or shifting production to produce needed equipment (67% and 62%, respectively) and collaborating with competitors (65%) in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Companies can also empower, trust, and support employees in taking initiative with the customers they serve, and emphasize transparency, accountability, and constructive partnerships to find solutions. Business Insider and Harvard Business Review offer ideas for evaluating the effectiveness of existing initiatives. Forums for open dialogue, such as The Policy Circle, may be helpful in building trust and understanding across different perspectives and backgrounds amongst associates.

Media

Bias, inaccuracy, and fake news are the most prevalent concerns when it comes to trusting media sources. The RAND Corporation’s Truth Decay Project takes a look at these concerns, investigating how the rise of social media and political and social polarization have contributed to “the diminishing role of facts and analysis in American public life.”

News organizations can take the steps to explain themselves, such as being more transparent in how they gather their news, how they are funded, or why they cannot divulge a source. Another idea is labeling technologies; much like labels that “instill confidence in our food, medicine, and other consumer goods,” such labels or disclaimers could also work to “instill trust in the news, video, people, and organizations we encounter on social networks.”

It is also up to individuals to do their due diligence and be responsible consumers of information. Educating ourselves to be news literate and seeking fact checkers can help us decide which outlets to turn to for news whether or not those are trustworthy sources of information, and if there are other viewpoints to consider. TedEd provides a few more tips (5 min):

Communities and Each Other

Civic engagement means more than just voting, but starting small in your community can have a significant impact. In their new book, The Upswing, Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett argue Americans can come together as communities, and Americans do still believe “their neighborhoods are a key place where interpersonal trust can be rebuilt if people work together on local projects, in turn radiating trust out to other sectors of the culture.”

For more on the role of strong communities, see The Policy Circle’s Stitching the Fabric of Neighborhoods Brief.

One significant component of communities is schools, where creating “a culture of respect for students, teachers, school administrators, and community members” reflects the collaborative goal of public schools. “One of the primary reasons our nation’s founders envisioned a vast public education system was to prepare youth to be active participants in our system of self-government.” Based on results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, only a quarter American students are proficient in civics and less than 20% proficient in U.S. History.

There are a number of ways the education system can prepare young Americans to be more active participants in society. The Center for Civic Education and the National Constitution Center offer resources to help teachers incorporate civics issues into classroom discussions and activities. Other options include service-oriented extracurriculars and giving students a voice in how their school operates. Outside of school, service programs like AmeriCorps allow participants of all ages to work with and in communities, advancing causes they care about and creatively responding to specific community needs. Individuals and communities can reach out to educators, school administrators, and even school boards or boards of education to understand how school districts teach civics, and what opportunities have the potential to be incorporated into curricula.

“If people feel engaged with their environment and with each other, and they can work together even in a small way, I think that builds a foundation for working together on more weighty issues.” – 32 year old female PEW Research survey respondent

Discussing credibility and trust often involves having difficult conversations with those who do not share the same thoughts or opinions. Most people would rather not have discussions with anyone who might disagree with them, but working across these differences to build relationships is the only way to understand why someone has a different opinion. The goal of building relationships, says former Montana Attorney General Tim Fox, is to “take on the tough issues and debate them without pointing fingers or laying blame or being divisive – being thoughtful and listening.” Communication in small discussions allows people to engage directly with one another, which can open doors of understanding and collaboration and result in innovative solutions that benefit everyone involved.

For how to get started, see The Policy Circle’s Civic Engagement Brief or explore the framework for facilitating complex discussions:

Loading...

Loading...

Thought Leaders & Additional Resources

- Robert Putnam, Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University and author of Bowling Alone and The Upswing, on trust and civic networks in this Freakonomics podcast

- Tim Fox, former Montana Attorney General and President of the National Association of Attorneys General, on trust and discourse in this podcast.

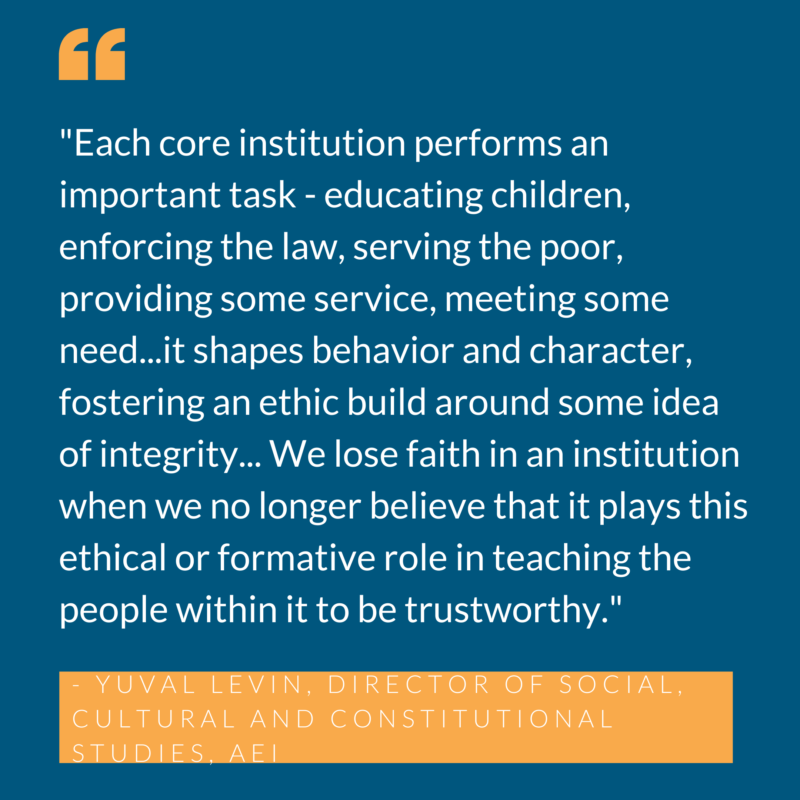

- Yuval Levin, Director of Social, Cultural and Constitutional Studies at American Enterprise Institute.

- Engaged – A Citizens Perspective on the Future of Civic Life by Andrew Sommers

- Gallup 2020 Confidence in Institutions survey

- January 2020, May 2020, January 2021, and January 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer reports

- The 2021 American Community Life Survey

- Gallup/Knight Foundation 2020 “Techlash” report

- University of Pennsylvania: Disagreeing without Being Disagreeable

- Persuasion: Cancel Culture Checklist

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Rebuilding Trust in America? Consider exploring the following: